The Ebers Papyrus is a medical record from ancient Egypt that offers over 842 treatments for diseases and accidents. It focused on the heart, the respiratory system, and diabetes in particular.

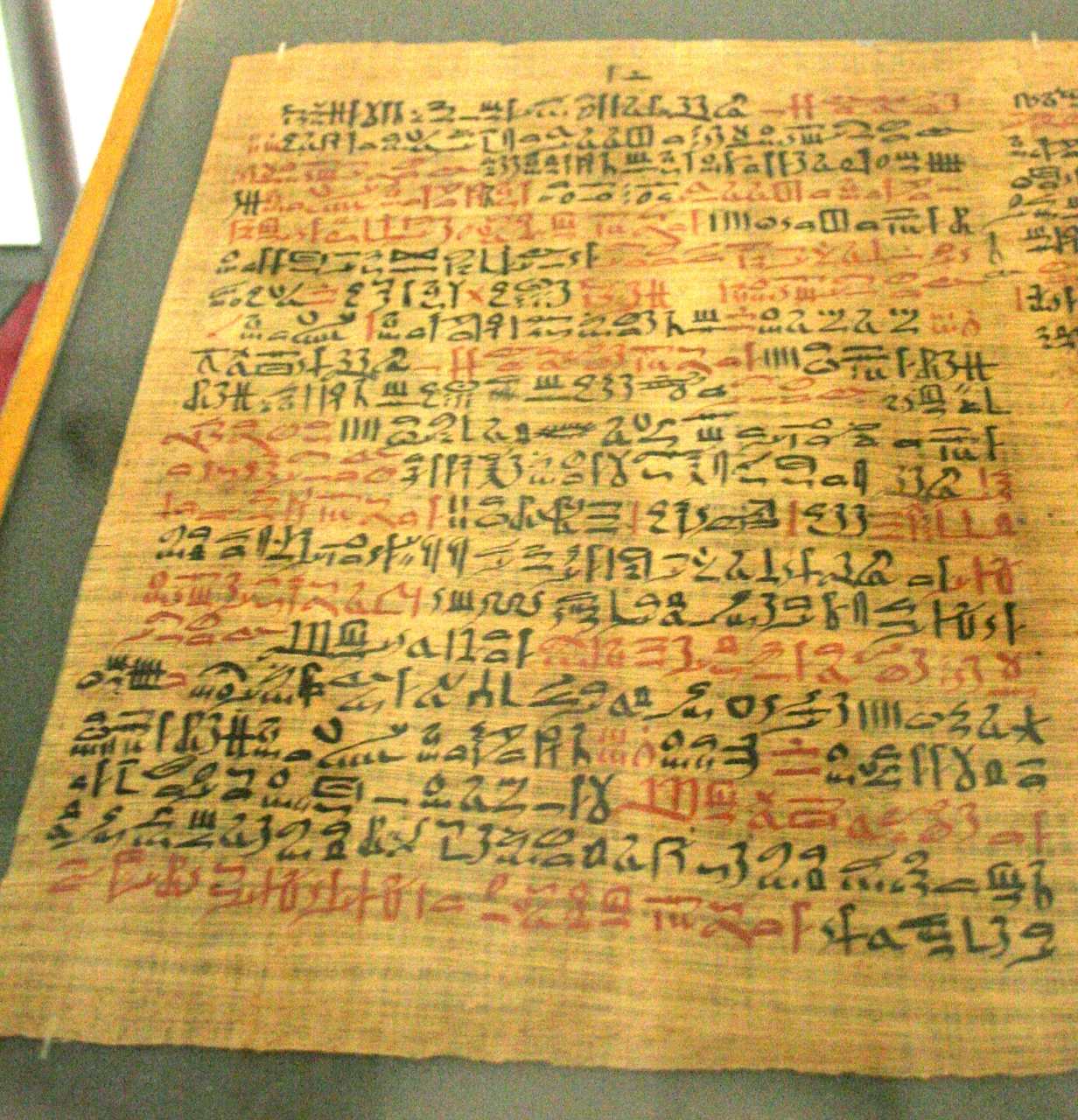

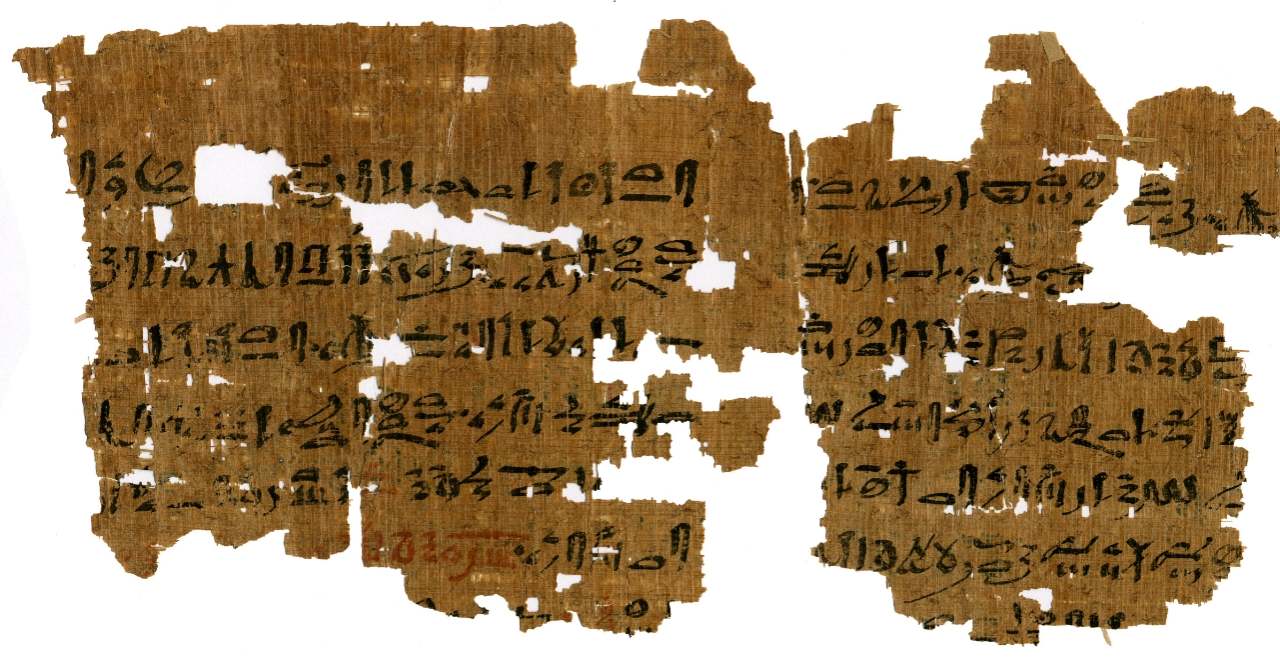

The Papyrus is almost 68 feet (21 metres) long and 12 inches (30 centimetres) broad. It is presently housed in Leipzig’s University Library in Germany. It’s divided into 22 lines. It was named after renowned Egyptologist Georg Ebers and is thought to have been created between 1550 and 1536 BC during the reign of Egyptian king Amenopis I.

The Ebers Papyrus is regarded as one of Egypt’s oldest and most comprehensive medical documents. It provides a colourful glimpse into Ancient Egyptian medicine and displays a merging of the scientific (known as the rational approach) and the magical-religious (known as the irrational method). It has been widely examined and re-translated nearly five times, and is recognised with providing considerable insight into Ancient Egypt’s cultural world between the 14th and 16th century BC.

Though the Ebers Papyrus contains a wealth of medical knowledge, there is just a little amount of evidence on how it was discovered. It was originally known as the Assasif Medical Papyrus of Thebes before being bought by Georg Ebers. It’s just as fascinating to learn how it came into the hands of Geog Ebers as it is to learn about the medical and spiritual treatments it discusses.

The myth & the history of the Ebers Papyrus

According to the legends, Georg Ebers and his wealthy sponsor Herr Gunther entered a rare collections shop run by a collector called Edwin Smith in Luxor (Thebes) in 1872. The Egyptology community had heard that he had strangely obtained the Assasif Medical Papyrus.

When Ebers and Gunther arrived, they questioned about Smith’s claim. A medical papyrus wrapped in mummy linen was handed to them by Smith. He stated that it was discovered between the legs of a mummy in the Theban necropolis’ El-Assasif District. Without further ado, Ebers and Gunther bought the medical papyrus and in 1875, they published it under the name Facsimile.

Though it is debatable whether the Ebers medical papyrus was authentic or a sophisticated forgery, the fact remains that Georg Ebers acquired the Assasif papyrus and proceeded to transcribe one of the greatest medical texts in recorded history.

The medical papyrus was produced by Ebers in a two-volume colour photo reproduction, complete with a hieroglyphic English to Latin translation. Joachim’s German translation emerged shortly after its publication in 1890, followed by H. Wreszinski’s translation of the hieratic into hieroglyphics in 1917.

Four further English translations of the Ebers Papyrus were completed: the first by Carl Von Klein in 1905, the second by Cyril P. Byron in 1930, the third by Bendiz Ebbel in 1937, and the fourth by physician and scholar Paul Ghalioungui. Ghalioungui’s copy is still the most comprehensive modern translation of the papyrus. It is also regarded one of the most valuable publications on the Ebers Papyrus.

Despite several attempts to accurately interpret the Ebers Papyrus, the papyrus continues to elude even the most experienced Egyptologists. A large number of cures have been found from what has been translated in the last 200 years, providing insight into the ancient Egyptian civilization.

The Ebers Papyrus: What have we learned?

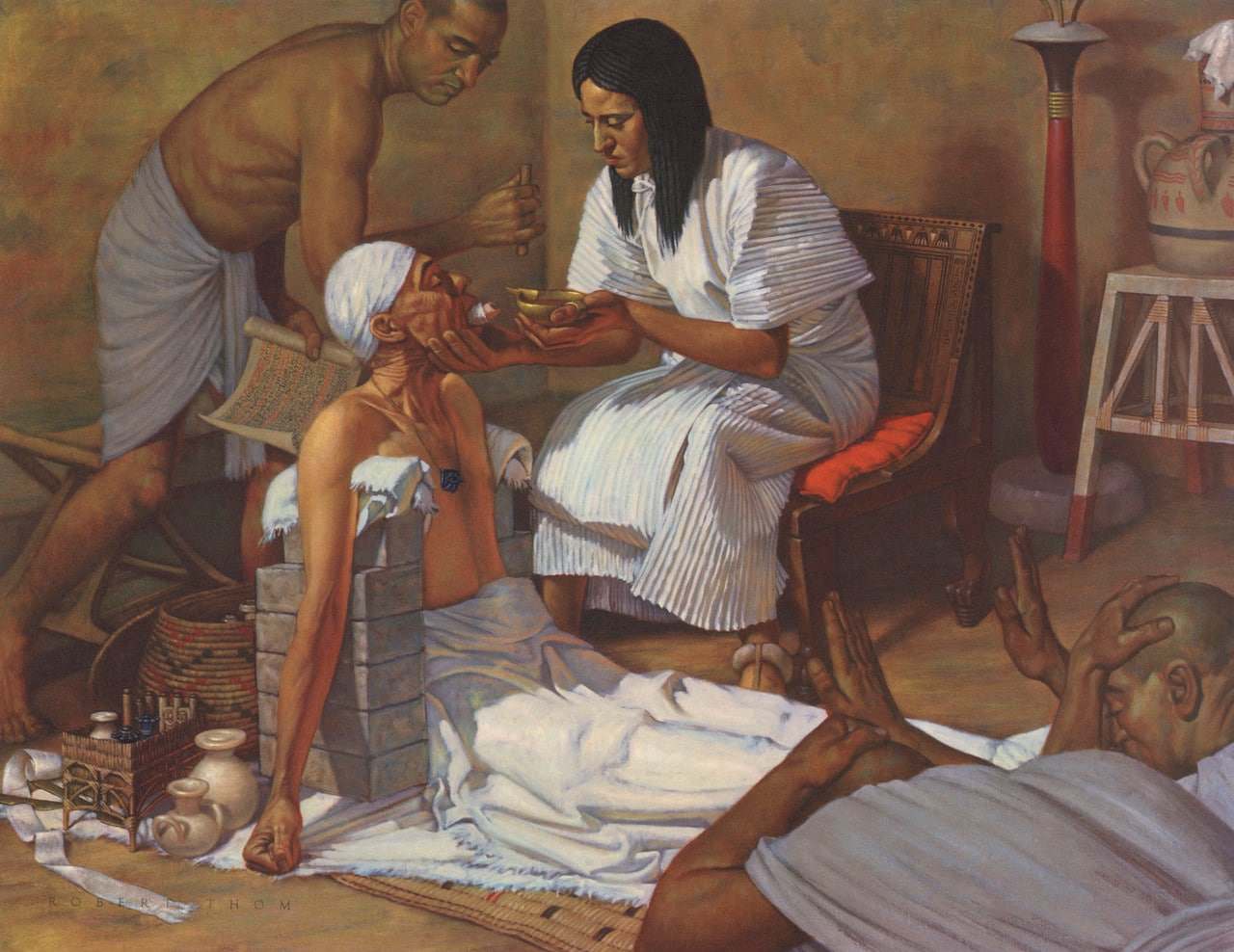

As previously stated, the Egyptian medical world was divided into two categories: “rational methods,” which were treatments based on modern scientific principles, and “irrational methods,” which involved magico-religious beliefs involving amulets, incantations, and written spells addressing ancient Egyptian gods. After all, there was a significant connection at the time between magic, religion, and medical wellness as a holistic experience. There was no such thing as bacterial or viral infection; only the gods’ wrath.

Although the Ebers Papyrus is dated to the 16th century BC (1550-1536 BC), linguistic evidence suggests that the text was taken from older sources dating back to Egypt’s 12th Dynasty. (From 1995 to 1775 BC). The Ebers Papyrus was written in hieratic, a cursive abbreviated version of hieroglyphics. It has 877 rubrics (section headers) in red ink, followed by black text.

The Ebers Papyrus is made up of 108 columns numbered 1–110. Each column has between 20 and 22 lines of text. The manuscript concludes with a calendar showing that it was written in Amenophis I’s ninth year, implying that it was created in 1536 BC.

It contains a wealth of knowledge about anatomy and physiology, toxicology, spells, and diabetic management. Among the treatments included in the book are those for treating animal-borne illnesses, plant irritants, and mineral poisons.

The majority of the papyrus focuses on therapy through the use of poultices, lotions, and other medical remedies. It has 842 pages of medicinal treatments and prescriptions that can be combined to make 328 mixtures for various diseases. There is, however, little to no proof that these mixtures were evaluated before to the prescription. Some believe such concoctions were inspired by particular element’s association with the gods.

According to archaeological, historical, and medical evidence, ancient Egyptian doctors possessed the knowledge and abilities to treat their patients rationally (treatments based on modern scientific principle). Nevertheless, the desire to combine magico-religious rituals (irrational methods) may have been a cultural requirement. If the practical applications failed, the ancient medical physicians could always turn to the spiritual ways to explain why a treatment was not functioning. One example can be found in a translation of a common cold healing spell:

“Flow out, fetid nose, flow out, son of fetid nose! Flow out, you who break bones, destroy the skull and make ill the seven holes of the head!” (Ebers Papyrus, line 763)

The ancient Egyptians paid close attention to the heart and cardiovascular system. They thought that the heart was in charge of regulating and transporting body fluids like as blood, tears, urine, and sperm. The Ebers Papyrus has an extensive section titled “the book of hearts” that details the blood supply and arteries that connect to every region of the human body. It also mentions mental problems like depression and dementia as important side effects of having a weak heart.

The papyrus also includes chapters on gastritis, pregnancy detection, gynaecology, contraception, parasites, eye difficulties, skin disorders, surgical treatment of malignant tumours, and bone setting.

There is one specific paragraph in the papyrus’ explanation of certain ailments that most experts believe is a precise statement of how to identify diabetes. Bendix Ebbell, for example, felt that Rubric 197 of the Ebers Papyrus matched the symptoms of diabetes mellitus. His translation of Ebers’ text is as follows:

“If you examine someone sick (in) the center of his being (and) is his body shrunken with disease at its limit; if you examine him not and you do find disease in (his body except for the surface of his ribs of which the members are like a pill you should then recite -a spell- against disease this in your house; you should also then prepare for him ingredients for treating it: bloodstone of Elephantine, ground; red grain; carob; cook in oil and honey; it should be eaten by him over mornings four for the suppression of his thirst and for curing his mortal illness.” (Ebers Papyrus, Rubric No. 197, Column 39, Line 7).

Though certain sections from the Ebers Papyrus read like mystical poetry at times, they also represent the first attempts at diagnosis that resemble those found in current medical books. The Ebers Papyrus, like many other papyri, should not be disregarded as theoretical prayers, but rather as practical guidance applicable to ancient Egyptian society and time. During a time when human misery was considered to be caused by the gods, these books were medicinal remedies for diseases and injuries.

The Ebers Papyrus provides valuable information into our current knowledge of ancient Egyptian life. Without the Ebers Papyrus and other texts, scientists and historians would only have mummies, art, and tombs to work with. These items may help with empirical facts, but without any written documentation to the world of their version of medicine, there would be no reference for the explanation of the ancient Egyptian world. However, there is still some suspicion about the paper.

The doubt

Given the numerous efforts to translate the Ebers Papyrus since its discovery, it has long been thought that most of its words were misunderstood due to the prejudice of each translator.

The Ebers Papyrus, according to Rosalie David, head of the KNH centre for biological Egyptology at the University of Manchester, may be useless. Rosalie stated in her 2008 Lancet paper that researching Egyptian papyri was a restricted and difficult source due to the extremely tiny fraction of work that is thought to be constant throughout 3,000 years of civilisation.

David goes on to say that current translators have run into issues with the language in the papers. She also observes that the identification of words and translations found in one text frequently contradicts the translated inscriptions found in another texts.

Translations, in her perspective, should remain exploratory and not be finalised. Because of the challenges mentioned by Rosalie David, most scholars have focused on analysing the mummified skeletal remains of individuals.

However, anatomical and radiological investigations on Egyptian mummies have shown more evidence that ancient Egyptian medical practitioners were highly skilled. These examinations showed repaired fractures and amputations, proving that ancient Egyptian surgeons were skilled at surgery and amputation. It has also been discovered that the ancient Egyptians were skilled in creating large prosthetic toes.

Mummy tissue, bone, hair, and tooth samples were analysed using histology, immunocytochemistry, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and DNA analysis. These tests aided in the identification of illnesses that afflicted the mummified persons. Certain ailments identified in the excavated mummies were treated with pharmaceutical treatments mentioned in medical papyri, demonstrating that some, if not all, of the medicines listed in writings such as the Ebers Papyrus may have been successful.

Medical papyri, such as the Ebers Papyrus, provide evidence for the origins of Egyptian medical and scientific literature. As Veronica M. Pagan points out in her World Neurosurgery article:

“These scrolls were used to pass down information from generation to generation, presumably kept on hand during war and used as a reference in daily life. Even with these extraordinary scrolls, it’s probable that above a certain degree, medical knowledge was transmitted verbally from master to pupil” (Pagan, 2011)

Further examination of the Ebers Papyrus, as well as the many others that exist, helps academics to see the connection between the spiritual and scientific in early ancient Egyptian medical knowledge. It enables one to grasp the vast quantity of scientific knowledge that was known in the past and that has been passed down through generations. It would be simple to ignore the past and believe that everything new was developed in the twenty-first century, but this may not be the case.

Final words

Rosalie David, on the other hand, urges for more research and is sceptical of the scrolls and their healing abilities. It is all too easy for individuals in the present day to disregard ancient medical treatments. The advances that have been made have progressed to the point where the deadliest illnesses and afflictions are on the edge of extinction. These improvements, on the other hand, are only marvelled at by those who live in the twenty-first century. Consider what a person from the 45th century might think of today’s practises.

After all, it will be fascinating to observe whether contemporary medical procedures in the Western world will be regarded as:

“A concoction of cultural and ideological cures devised to alleviate ailments that danced a tight line between their polytheistic gods and the invisible divinity known as ‘science.’ If only these folks had known that the spleen and appendix were the most vital organs, they may have been more than simply 21st-century neophytes.”

A sentiment that us in the current world would see as both stupid and disdainful, but which our forefathers may deem historically and archaeologically acceptable. Perhaps context is required for the ancient Egyptians in this regard. The ancient gods and their healing procedures were real in their world.