The Great Pyramids of Giza stand as a testament to the ingenuity of the ancient Egyptians. For centuries, scholars and historians have wondered how a society with limited technology and resources managed to construct such an impressive structure. In a groundbreaking discovery, archaeologists uncovered the Diary of Merer, shedding new light on the construction methods used during ancient Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty. This 4,500-year-old papyrus, the oldest in the world, offers detailed insight into the transportation of massive limestone and granite blocks, ultimately revealing the incredible engineering feat behind the Great Pyramids of Giza.

An insight into Merer’s Diary

Merer, a middle-ranking official referred to as an inspector (sHD), authored a series of papyrus logbooks now known as “The Diary of Merer” or “Papyrus Jarf.” Dating back to the 27th year of Pharaoh Khufu’s reign, these logbooks were written in hieratic hieroglyphs and primarily consist of daily activity lists of Merer and his crew. The best-preserved sections, labeled Papyrus Jarf A and B, provide documentation of the transportation of white limestone blocks from the Tura quarries to Giza via boat.

The rediscovery of the texts

In 2013, French archaeologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard, leading a mission at Wadi al-Jarf on the Red Sea coast, uncovered the papyri buried in front of man-made caves used to store boats. This discovery has been hailed as one of the most significant findings in Egypt during the 21st century. Tallet and Mark Lehner have even called it the “Red Sea scrolls,” comparing them to the “Dead Sea Scrolls,” to emphasize its significance. Parts of the papyri are currently on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The revealed construction techniques

The Merer’s Diary, along with other archaeological excavations, has provided new insights into the construction methods employed by the ancient Egyptians:

- Artificial Ports: The construction of ports was a pivotal moment in Egyptian history, opening up lucrative trade opportunities and establishing connections with distant lands.

- River Transportation: Merer’s diary reveals the usage of wooden boats, specially designed with planks and ropes, capable of carrying stones weighing up to 15 tonnes. These boats were rowed downstream along the Nile River, ultimately transporting the stones from Tura to Giza. About every ten days, two or three round trips were done, shipping perhaps 30 blocks of 2–3 tonnes each, amounting to 200 blocks per month.

- Ingenious Waterworks: Every summer, the Nile floods allowed the Egyptians to divert water through a manmade canal system, creating an inland port very close to the pyramid construction site. This system facilitated easy docking of the boats, enabling efficient transportation of materials.

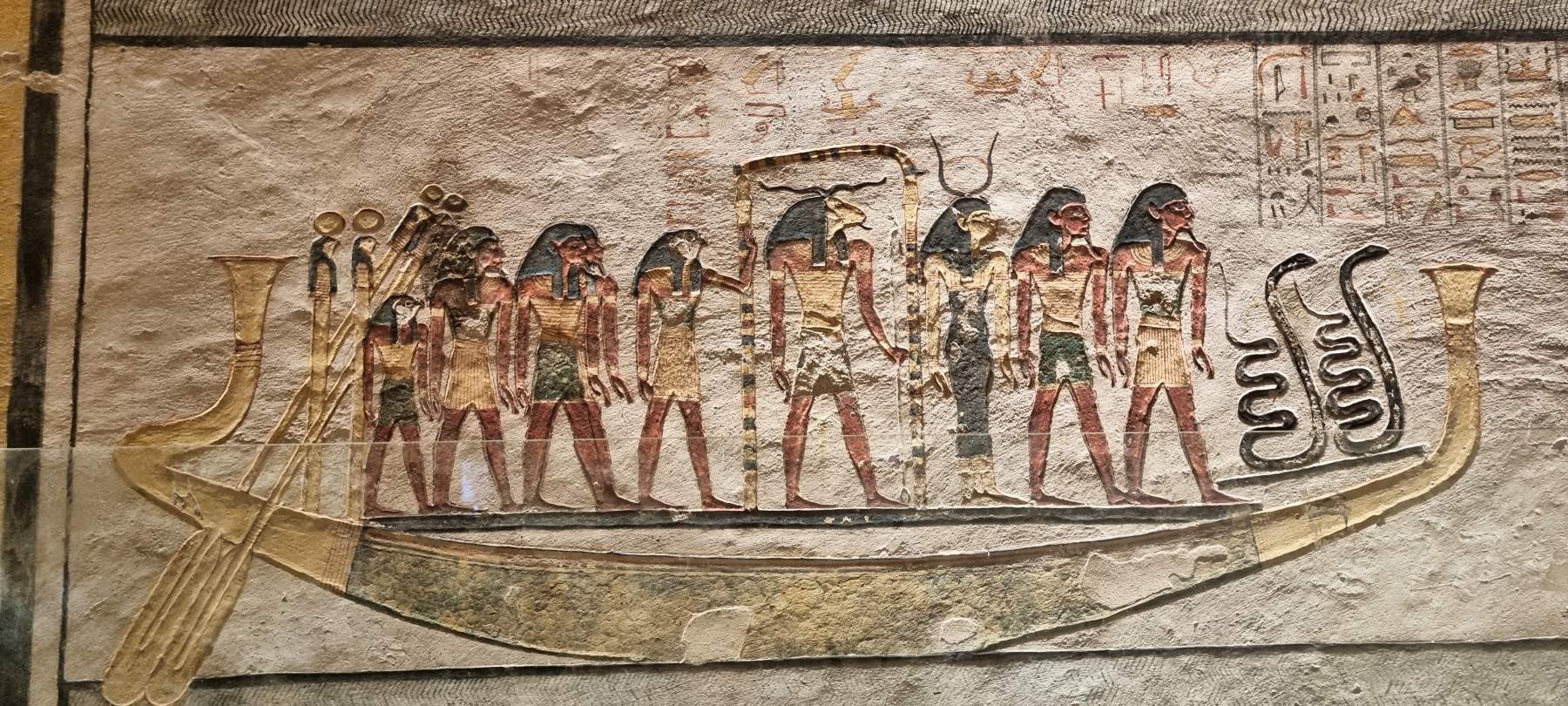

- Intricate Boat Assembly: By using 3D scans of ship planks and studying tomb carvings and ancient dismantled ships, archaeologist Mohamed Abd El-Maguid has meticulously reconstructed an Egyptian boat. Sewn together with ropes instead of nails or wood pegs, this ancient boat serves as a testament to the incredible craftsmanship of the time.

- Great Pyramid’s real name: The diary also mentions the original name of the Great Pyramid: Akhet-Khufu, meaning “Horizon of Khufu”.

- In addition to Merer, a few other people are mentioned in the fragments. The most important is Ankhhaf (half-brother of Pharaoh Khufu), known from other sources, who is believed to have been a prince and vizier under Khufu and/or Khafre. In the papyri he is called a nobleman (Iry-pat) and overseer of Ra-shi-Khufu, (perhaps) the harbour at Giza.

Implications and legacy

The discovery of Merer’s Diary and other artifacts has also revealed evidence of a vast settlement supporting an estimated 20,000 workers involved in the project. Archeological evidence points to a society that valued and cared for its labor force, providing food, shelter, and prestige for those engaged in pyramid construction. Moreover, this feat of engineering demonstrated the Egyptians’ ability to establish complex infrastructure systems that extended far beyond the pyramid itself. These systems would shape the civilization for millennia to come.

Final thoughts

Merer’s Diary offers valuable information on the transportation of stone blocks for the construction of the Giza Pyramids through water canals and boats. However, not everyone is convinced with the information recovered from Merer’s diary. According to some independent researchers, it leaves unanswered questions on whether these boats were capable of maneuvering the largest stones used, casting doubt on their practicality. Additionally, the diary fails to detail the precise method employed by ancient workers to assemble and fit these massive stones together, leaving the mechanics behind the creation of these monumental structures largely shrouded in mystery.

Is it possible that Merer, the ancient Egyptian official mentioned in the texts and logbooks, hid or manipulated information about the actual construction process of the Giza Pyramids? Throughout history, ancient texts and writings have frequently been manipulated, exaggerated, or degraded by authors under the influence of authorities and reigns. On the other side, many civilizations tried to keep their construction methods and architectural techniques secret from competing kingdoms. Therefore, it wouldn’t be surprising if Merer or others involved in the construction of the monument distorted the truth or deliberately concealed certain aspects to maintain a competitive advantage.

Between the existence and non-existence of super advanced technology or ancient giants, the discovery of Merer’s Diary remains truly remarkable in unraveling the secrets of ancient Egypt and the enigmatic minds of its inhabitants.