Known for its numerous therapeutic and culinary uses, it is a tale of a botanical marvel that vanished from existence, leaving behind a trail of intrigue and fascination that continues to captivate researchers today.

Silphium, an ancient plant that held a special place in the hearts of the Romans and Greeks, might still be around, unbeknownst to us. This mysterious plant, once a prized possession of emperors and a staple in ancient kitchens and apothecaries, was a cure-all wonder drug. The plant’s disappearance from history is a fascinating tale of demand and extinction. It’s an ancient botanical marvel that left behind a trail of intrigue and fascination that continues to captivate researchers today.

The legendary Silphium

Silphium was a highly sought-after plant, native to the region of Cyrene in Northern Africa, now modern-day Shahhat, Libya. It reportedly belonged to the Ferula genus, which comprises of plants commonly known as the “giant fennels”. The plant was characterized by its sturdy roots covered in dark bark, a hollow stem akin to fennel, and leaves that resembled celery.

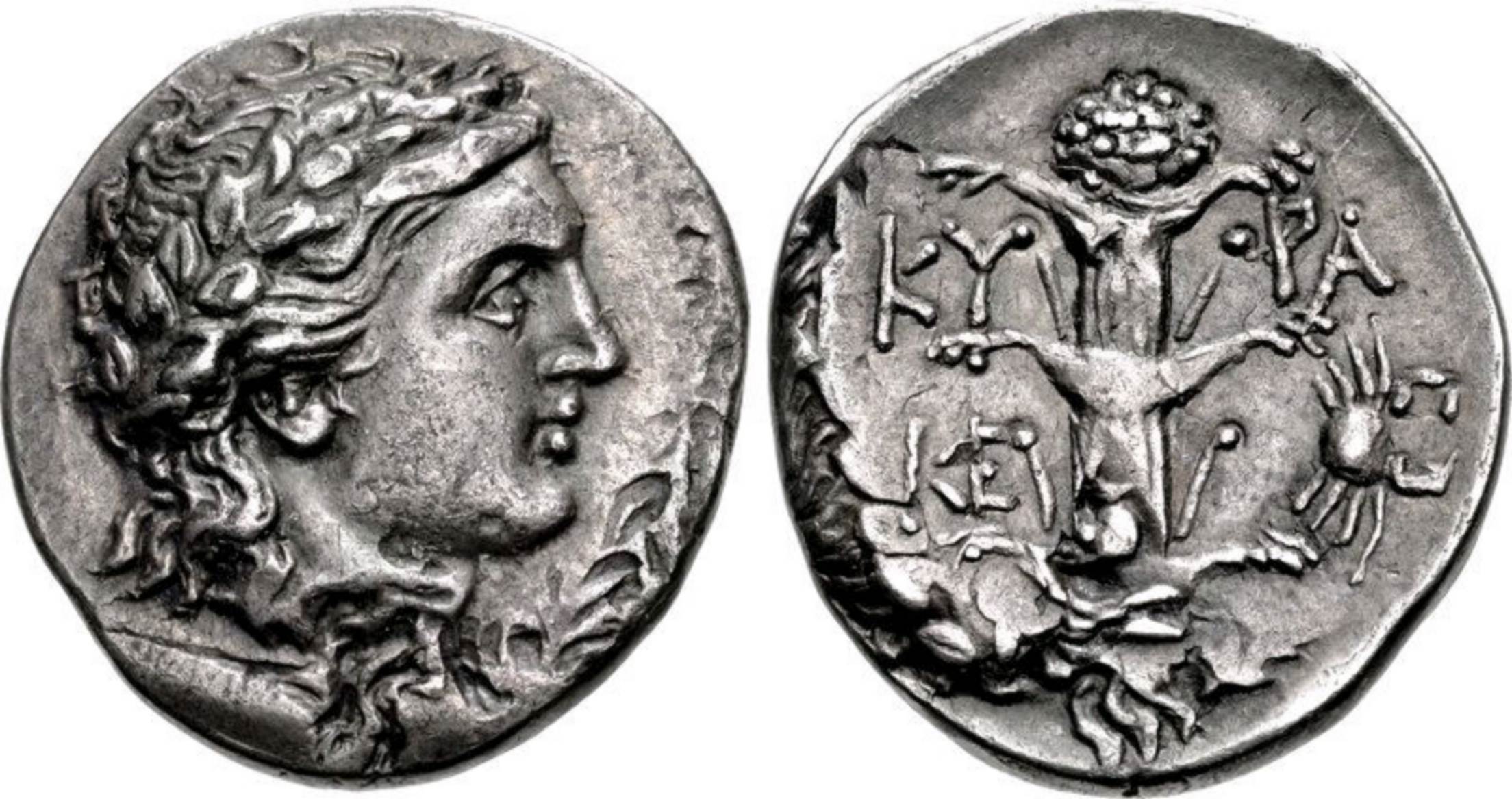

Attempts to cultivate Silphium outside its native region, particularly in Greece, were unsuccessful. The wild plant flourished solely in Cyrene, where it played a pivotal role in the local economy and was extensively traded with Greece and Rome. Its significant value is depicted in the coins of Cyrene, which often featured images of Silphium or its seeds.

The demand for Silphium was so high that it was said to be worth its weight in silver. The Roman Emperor Augustus sought to regulate its distribution by demanding that all harvests of Silphium and its juices be sent to him as a tribute to Rome.

Silphium: a culinary delight

Silphium was a popular ingredient in the culinary world of ancient Greece and Rome. Its stalks and leaves were used as seasoning, often grated over food like parmesan or mixed into sauces and salts. The leaves were also added to salads for a healthier option, while the crunchy stalks were enjoyed roasted, boiled, or sautéed.

Moreover, every part of the plant, including the roots, was consumed. The roots were often enjoyed after being dipped in vinegar. A notable mention of Silphium in ancient cuisine can be found in De Re Coquinaria — a 5th-century Roman cookbook by Apicius, which includes a recipe for “oxygarum sauce”, a popular fish and vinegar sauce that used Silphium among its main ingredients.

Silphium was also used to enhance the flavor of pine kernels, which were then used to season various dishes. Interestingly, Silphium was not only consumed by humans but was also used to fatten cattle and sheep, allegedly making the meat tastier upon slaughter.

Silphium: the medical marvel

In the early days of modern medicine, Silphium found its place as a panacea. The Roman author Pliny the Elder’s encyclopedic work, Naturalis Historia, frequently mentions Silphium. Furthermore, renowned physicians like Galen and Hippocrates wrote about their medical practices using Silphium.

Silphium was prescribed as a cure-all ingredient for a broad range of ailments, including coughs, sore throats, headaches, fevers, epilepsy, goiters, warts, hernias, and “growths of the anus”. Moreover, a poultice of Silphium was believed to cure tumors, heart inflammation, toothaches, and even tuberculosis.

But that’s not all. Silphium was also used to prevent tetanus and rabies from feral dog bites, to grow hair for those with alopecia, and to induce labor in expectant mothers.

Silphium: aphrodisiac and contraceptive

Aside from its culinary and medicinal uses, Silphium was renowned for its aphrodisiac properties and was considered the world’s most effective birth control at the time. The heart-shaped seeds of the plant were believed to increase libido in men and cause erections.

For women, Silphium was used to manage hormonal issues and to induce menstruation. The plant’s use as a contraceptive and abortifacient has been extensively recorded. Women consumed Silphium mixed with wine to “move menstruation”, a practice documented by Pliny the Elder. Furthermore, it was believed to terminate existing pregnancies by causing the uterine lining to shed, preventing the fetus’s growth and leading to its expulsion from the

body.

The heart shape of the silphium seeds might have been the source of the traditional heart symbol, a globally recognized image of love today.

The disappearance of Silphium

Despite its widespread use and popularity, Silphium disappeared from history. The extinction of Silphium is a subject of ongoing debate. Overharvesting could have played a significant role in the loss of this species. As Silphium could only grow successfully in the wild in Cyrene, the land might have been overexploited due to years of harvesting the crop.

Due to a combination of rainfall and mineral-rich soil, there were limits to how many plants could be grown at one time in Cyrene. It is said that the Cyrenians tried to balance the harvests. However, the plant eventually was harvested to extinction by the end of the first century AD.

The last stalk of silphium was reportedly harvested and given to Roman Emperor Nero as an “oddity.” According to Pliny the Elder, Nero promptly ate the gift (clearly, he had been poorly informed on the plant’s usages).

Other factors such as overgrazing by sheep, climate change, and desertification might also have contributed to making the environment and soil unsuitable for Silphium to grow.

A living memory?

Despite its disappearance, the legacy of Silphium endures. According to some researchers, the plant might still be growing in the wild in Northern Africa, unrecognized by the modern world. Until such a discovery is made, Silphium remains an enigma — a plant that once held a revered place in ancient societies, now lost to time.

So, do you think that fields of Silphium might still be blooming, unrecognized, somewhere in Northern Africa?