Millions of years ago, Antarctica was part of Gondwana, a large landmass located in the Southern Hemisphere. During this time, the area now covered in ice was actually home to trees near the South Pole.

The discovery of intricate fossils of these trees is now showing how these plants flourished and what the forests will potentially resemble as temperatures continue to rise in the present day.

Erik Gulbranson, an expert in paleoecology at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, pointed out that, Antarctica preserves an ecologic history of polar biomes that ranges for about 400 million years, which is basically the entirety of plant evolution.

Can Antarctica have trees?

When one glance at Antarctica’s current frigid atmosphere, it is difficult to envision the lush forests that once existed. To find the fossil remains, Gulbranson and his team had to fly to snowfields, hike over glaciers and endure the intense cold winds. However, from approximately 400 million to 14 million years ago, the landscape of the southern continent was drastically different and much more lush. The climate was also milder, yet the vegetation that flourished in the lower latitudes still had to endure 24-hour darkness in the winter and perpetual daylight in the summer, similar to the conditions of today.

Gulbranson and his colleagues are researching the Permian-Triassic mass extinction, which happened 252 million years ago and caused the deaths of 95 percent of Earth’s species. This extinction is believed to have been caused by huge amounts of greenhouse gases emitted from volcanoes, which resulted in record-breaking temperatures and acidified oceans. There are similarities between this extinction and current climate change, which is not as drastic but is still influenced by greenhouse gases, Gulbranson stated.

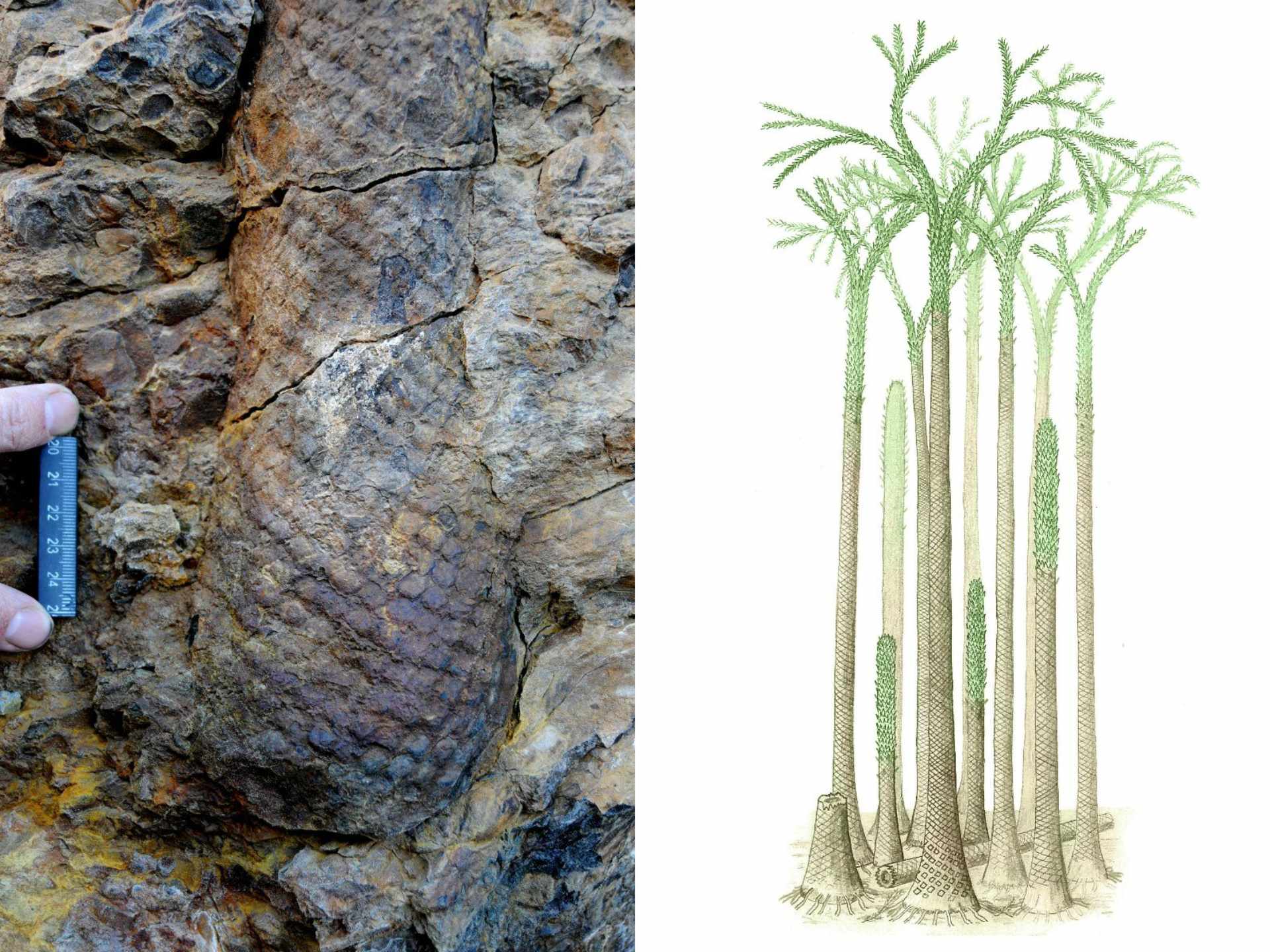

In the period before the end-Permian mass extinction, Glossopteris trees were the predominant species of tree in the southern polar forests, said Gulbranson in an interview with Live Science. These trees could reach heights of 65 to 131 feet (20 to 40 meters) and had large, flat leaves longer than even a human arm, according to Gulbranson.

Before the Permian extinction, these trees covered the land between the 35th parallel South and the South Pole. (The 35th parallel south is a circle of latitude that is 35 degrees south of the Earth’s equatorial plane. It crosses the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, Australasia, the Pacific Ocean, and South America.)

Contrasting circumstances: Before and after

In 2016, during a fossil-seeking expedition to Antarctica, Gulbranson and his team stumbled upon the earliest documented polar forest from the south pole. Although they haven’t pinpointed an exact date, they guess that it flourished around 280 million years back before being rapidly buried in volcanic ash, which kept it in perfect condition down to the cellular level, as the researchers reported.

According to Gulbranson, they need to visit Antarctica repeatedly to further explore the two sites that have fossils from before and after the Permian extinction. The forests underwent a transformation after the extinction, with Glossopteris no longer present and a new blend of deciduous and evergreen trees, such as relatives of the modern ginkgo, taking its place.

Gulbranson mentioned that they are attempting to discover what precisely caused the shifts to take place, though they currently lack a substantial understanding on the matter.

Gulbranson, also an expert in geochemistry, pointed out that the plants encased in rock are so well-preserved that their proteins’ amino acid components can still be extracted. Investigating these chemical constituents might be useful to understand why the trees survived the bizarre lighting in the south and what caused Glossopteris’s demise, he suggested.

Fortunately, in their further study, the research team (consisting of members from the US, Germany, Argentina, Italy, and France) will have access to helicopters in order to get closer to the rugged outcrops in the Transantarctic Mountains, where the fossilized forests are located. The team will stay in the area for several months, taking helicopter trips to the outcrops when the weather permits. The 24-hour sunlight in the region allows for much longer day trips, even midnight expeditions that involve mountaineering and fieldwork, according to Gulbranson.