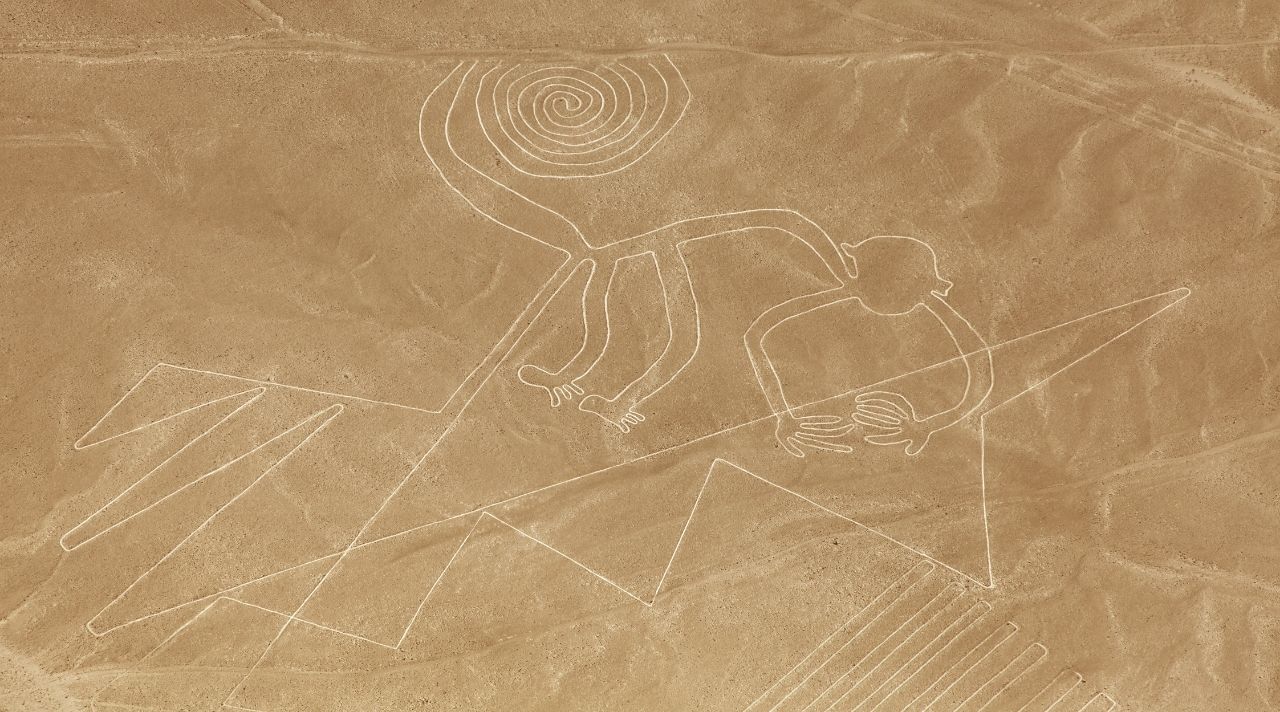

An ancient society developed around an agrarian economy that comprised maize, squash, yucca, and other crops about 2,000 years ago in a coastal area of Peru that receives less than 4 millimeters of rain yearly. Their legacy, known as the Nazca, is best known to the world today through the Nazca Lines, ancient geoglyphs in the desert that range from simple lines to depictions of monkeys, fish, lizards, and many other intriguing figures.

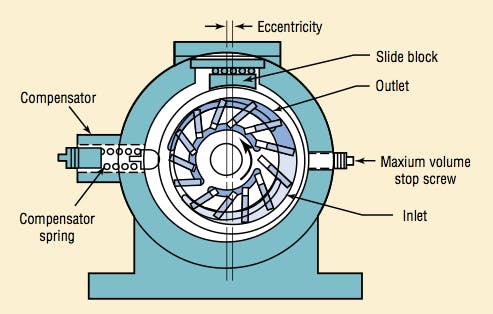

While the accepted theory is that the lines may have been built for religious reasons, the Nazcas’ sophisticated architecture of subterranean aqueducts was the vital power that sustained their whole society. The system tapped into naturally existent subterranean reservoirs at the base of the Nazca mountains, funneling the water to the sea via a series of horizontal tunnels. There were dozens, if not hundreds, of spiral-shaped wells known as puquios, dotting the surface of these underground aqueducts.

From 1000 BC until 750 AD, the Nazca people ruled the region. The origins of the aqueducts’ formation had been a mystery for decades, but according to an essay published by Rosa Lasaponara of the Institute of Methodologies for Environmental Analysis in Italy, her team had solved the mystery.

The scientists used satellite photography to eventually identify the puquios as ‘a complex hydraulic system built to extract water from subterranean aquifers’. Rosa Lasaponara believes that her discovery explains how the original Nazca people were able to exist in a water-stressed environment. Furthermore, they not only survived, but also developed agriculture.

The puquios are located in the same area as the well-known Nazca lines and the significance of these ancient holes has been extensively disputed. Some historians and archaeologists speculated that they were part of an advanced irrigation system. Others speculated that these were ceremonial graves.

Many experts were perplexed as to how the native inhabitants of Nazca were able to thrive in an environment where droughts may persist for years at a time.

Lasaponara and her team were able to better grasp how the puquios were dispersed over the Nazca region, as well as where they ran in relation to adjacent villages ― which are simpler to date ― by using satellite photography.

“What is obvious now is that the puquio system had to be considerably more sophisticated than it seems today,” Lasaponara adds. “By utilizing an unlimited water supply throughout the year, the puquio system helped to extensive valley agriculture in one of the world’s most dry regions.”

The origin of the puquios has remained a mystery to scholars since standard carbon dating procedures could not be used on the tunnels. Neither did the Nazca leave any hints as to where they came from. With the noteworthy exception of the Maya, they, like many other South American cultures, lacked a writing system.

“The creation of the puquios necessitated the application of very advanced technology,” Lasaponara explains. Not only did the architects of the puquios require a thorough grasp of the area’s geology and seasonal changes in water availability, but maintaining the canals was a technical difficulty due to their distribution over tectonic faults.

“What is truly amazing is the enormous amount of labor, planning, and cooperation necessary for their creation and ongoing maintenance,” Lasaponara says.

That meant a consistent, steady water supply for generations in a region that is one of the driest on the planet. To say, the most ambitious hydraulic project in the Nazca area made water available all year, not just for agriculture and irrigation, but also for domestic needs.

The Nazca region’s area has been researched for many decades, yet it still holds many surprises. A few years ago, David Jonson, a former teacher, cameraman, and independent researcher from Poughkeepsie, New York, proposed his own idea regarding the Nazca geoglyphs. He argues that the patterns serve as maps and points to subsurface water flows that feed the puquios system.

He has been studying the renowned Nazca lines blanket, which covers around 280 square miles, since the early 1990s (725.2 sq. km). Jonson spent many weeks in Peru’s coastal plain region investigating the lines, which are considered one of the world’s greatest mysteries.

The “Mysterious Holes of Peru,” according to the researcher, are certainly destined to become a great illustration of an ancient people’s technical and creative ability transported into South America from the Mediterranean Region. He argues that “sometime after arriving, the immigrants had, possibly out of necessity, built a simple, inexpensive, non-labor intensive water collecting and filtering system.”