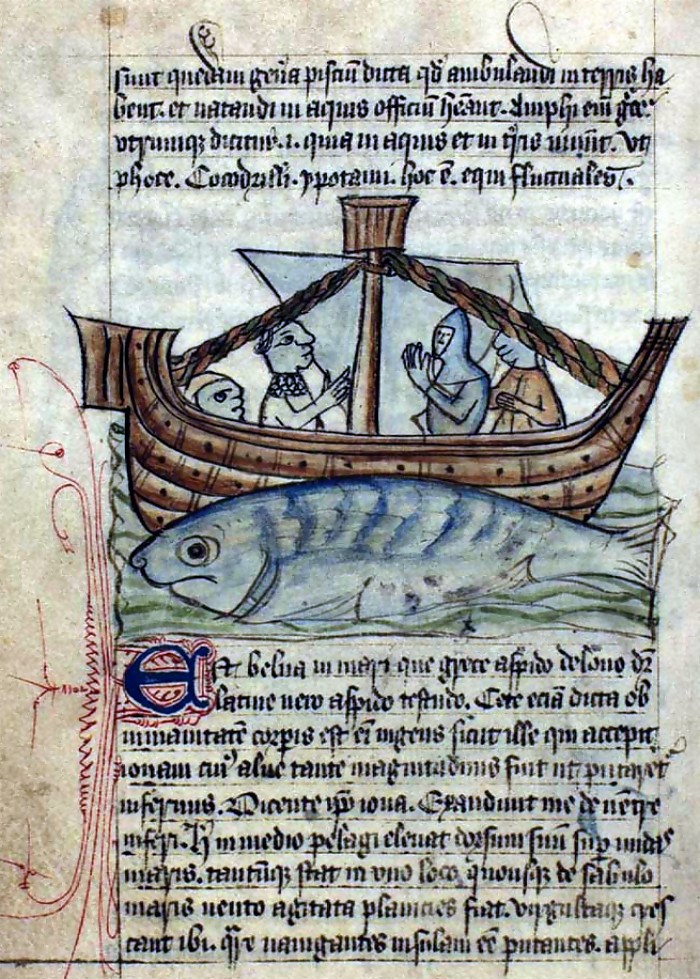

The name Aspidochelone combines the Greek aspis (meaning either “asp” or “shield”), and chelone, the turtle. The earliest accounts of the Aspidochelone can be traced back to medieval bestiaries and literary works. It is often depicted as a gigantic sea creature, sometimes resembling a whale or a sea turtle, but possessing distinct features such as a spiky shell or coral-covered back.

The Aspidochelone is said to have a deceptively inviting appearance, luring sailors with its calm and tranquil waters. Sailors who venture too close to what they believe to be an island would anchor their ships to explore, only to find themselves trapped on the creature’s back.

Once the sailors are on its back, the Aspidochelone would suddenly dive back into the depths of the ocean, dragging the unfortunate crew to their doom. The creature is often associated with voracious appetite, devouring everything and everyone in its path.

Aspidochelone’s legend has been subject to various symbolic interpretations over the centuries. Some believe it represents the dangers and uncertainties of the sea, warning sailors of the perils of the open waters. Others see it as a metaphor for the allure of deceptive temptations, cautioning against falling into treacherous traps.

The legend of the Aspidochelone has been passed down through generations of sailors, becoming a part of maritime folklore and nautical lore. Sailors would share tales of the creature during their journeys, reminding one another to exercise caution and remain vigilant at sea.

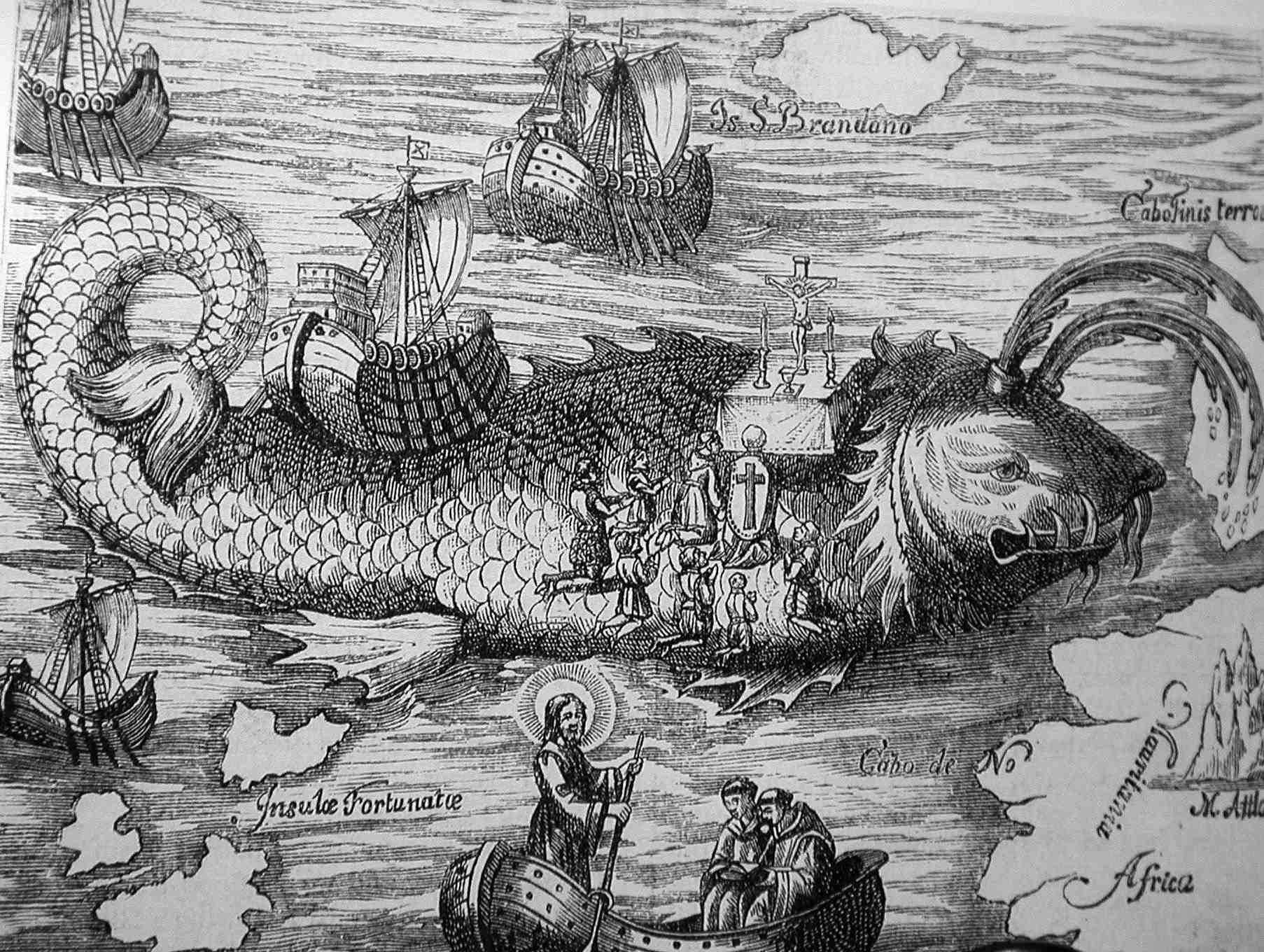

The Aspidochelone’s myth has also inspired numerous works of art and literature over the centuries. It has appeared in medieval manuscripts, paintings, and maritime-themed literature, further solidifying its place in cultural history.

Sea monsters so great as islands appear in biblical comentaries. Basil of Caesarea in his Hexameron says the following about the “great whales” (hebrew tannin) mentioned in the fifth day of creation (Genesis 1:21):

Scripture gives them the name of great not because they are greater than a shrimp and a sprat, but because the size of their bodies equals that of great hills. Thus when they swim on the surface of the waters one often sees them appear like islands. But these monstrous creatures do not frequent our coasts and shores; they inhabit the Atlantic ocean. Such are these animals created to strike us with terror and awe. If now you hear say that the greatest vessels, sailing with full sails, are easily stopped by a very small fish, by the remora, and so forcibly that the ship remains motionless for a long time, as if it had taken root in the middle of the sea, do you not see in this little creature a like proof of the power of the Creator?

The Pseudo-Eustatius Commentary on the Hexameron connects this passage with Aspidochelone mentioned in the Physiologus.

A related story is the Jonah’s Whale legend. Pliny the Elder’s Natural History tells the story of a giant fish, which he names pristis, of immense size.

The Arabic polymath Al-Jahiz mentions three monsters that are supposed to live in the sea: the tanin (sea-dragon), the saratan (crab) and the bala (whale). About the second (saratan), he said the following:

As to the sarathan, I have never yet met anybody who could assure me he had seen it with his own eyes. Of course, if we were to believe all that sailors tell […] for they claim that on occasions they have landed on certain islands having woods and valleys and fissures and have lit a great fire; and when the monster felt the fire on its back, it began to glide away with them and all the plants growing on it, so that only such as managed to flee were saved. This tale outdoes the most fabulous and preposterous of stories.

This monster is mentioned in The Wonders of Creation, written by Al Qazwini, and in the first voyage of Sinbad the Sailor in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights.

A similar monster appears in the Legend of Saint Brendan, where it was called Jasconius. Because of its size, Brendan and his fellow voyagers mistake it for an island and land to make camp. They celebrate Easter on the sleeping giant’s back, but awaken it when they light their campfire. They race to their ship, and Brendan explains that the moving island is really Jasconius, who labors unsuccessfully to put his tail in its mouth.

Another similar tale is told by the Old English poem “The Whale”, where the monster appears under the name Fastitocalon. The poem has an unknown author, and is one of three poems in the Old English Physiologus, also known as the Bestiary, in the Exeter Book – a large codex of Old English poetry, believed to have been produced in the late tenth century AD.

In modern times, the Aspidochelone continues to influence popular culture, appearing in various forms of media such as web series, movies, and video games. Its enduring legacy serves as a testament to the enduring power of mythical creatures in captivating human imagination.