Archaeologists in Israel have discovered fascinating evidence of brain surgery performed during the Late Bronze Age, dating back over 3,500 years. The discovery was made in the ancient city of Megiddo, which was inhabited during the Bronze Age. The excavations were led by a team from the Brown University’s Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World.

The discovery of brain surgery in prehistoric times is rare, and this latest finding offers up intriguing possibilities about the medical practices of ancient people. The researchers believe that the surgery was performed in ancient times to alleviate the symptoms of epilepsy, which they found on one skull.

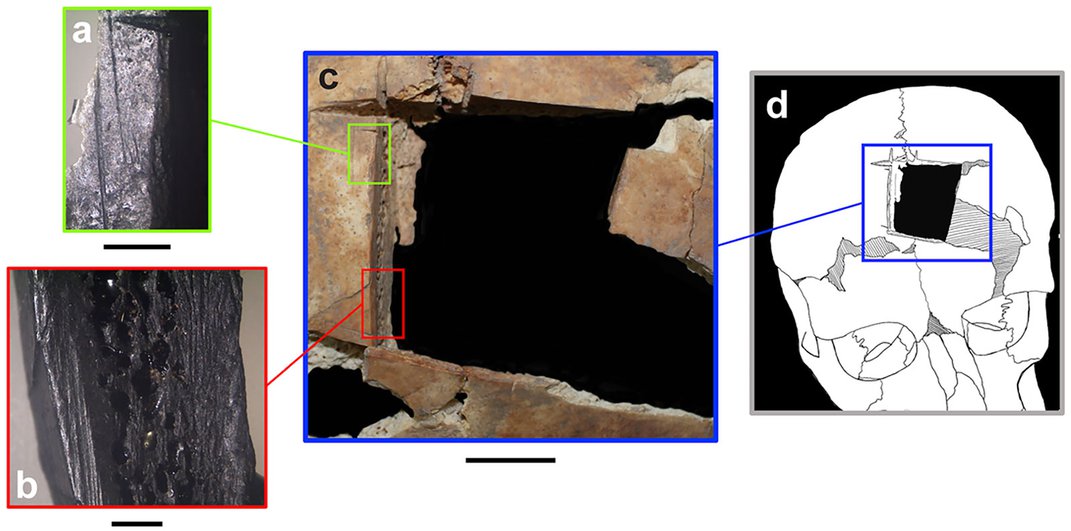

In 2016, while excavating the historic site – beneath the floor of a Late Bronze Age-era building – the archaeologists uncovered the remnants of two young upper-class brothers who lived in Megiddo around the 15th century BC. The team discovered that one of the brothers had undergone an angular notched trephination, a form of cranial surgery, not long before he passed away.

The surgery process entails cutting the scalp, carving four intersecting lines in the skull to make a square-shaped hole which the researchers believe was made using a small tool with a sharp beveled edge, possibly by a trained surgeon. The trephination is located on the top of the man’s skull, above the forehead and was likely the earliest example of such procedure in the Ancient Near East.

The remains also showed signs of the individual having also suffered from cranial trauma, likely caused by a blunt instrument, before the surgery was performed. The man’s skull had healed, and he lived on for several years before his death.

The discovery of brain surgery in the ancient times is particularly interesting, as it shows that even in the antiquity, human beings were capable of advanced medical practices. The researchers believe that this surgery was carried out by specialized doctors who played a crucial role in ancient society.

The findings have been published in the International Journal of PLOS ONE, discussing the practice and effectiveness of such surgeries in the ancient era. They stated, “The presence of a trephination on Individual 1 further represents an unusual and high-level intervention that indicates access to the services of a trained practitioner who administered this treatment shortly before death. This trephination thus illuminates the intersection of biological circumstance and social action in antiquity.”

However, the researchers noted that there is still a lot that archaeologists must uncover over the last 200 years to know more about trephination.

For instance, it is unclear why some trephinations are round, indicating the use of an analog drill, while others are square or triangular. Furthermore, it is unclear what ancient peoples were even trying to heal and how prevalent the treatment was in each region.

According to historical data, Megiddo was situated over a significant land route known as the Via Maris that linked Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia 4,000 years ago. By the 19th century BC, the city had developed into one of the richest in the region as it brimmed with temples, palaces, gates, fortifications, and many more. And the two brothers’ remains, according to the researchers, came from a residential area next to the late Bronze Age palace at Megiddo, indicating that they were elite citizens and perhaps even royalty.

The study also highlights the importance of the excavations being carried out, and the value of examining the remains of ancient people. By examining bone fragments and artifacts from the past, archaeologists can piece together evidence about ancient societies and their beliefs, practices, and medical knowledge.

This discovery of prehistoric brain surgery has opened up a new avenue of research and findings in the field of paleopathology, which involves studying ancient pathology and disease, and revealing how humans have adapted and evolved to survive.

As technology advances, and with new discoveries being made, there is still much to learn about our ancient past, and the potential clues it holds to our medical and social history.