In the west of the Al-Nafud Desert, 220 kilometres from the city of Tabuk, is the ancient Taima Oasis. In this deserted place, among the sands and rocks, one mystery especially attracts tourists – Al Naslaa, a huge formation of sandstone, as if cut in half by a giant’s sword. There are two parts of this giant cobblestone on fragile support, as the locals say, from time immemorial.

The Al Nafoud Desert is a huge sandy sea in the north of the Arabian Peninsula, 290 km long and 225 km wide. In some places, there are shrubs and stunted trees, but more often there are tall, dark red dunes resembling crescent-shaped dunes. This shape is due to strong winds blowing sand to one side. This is one of the driest places – it rains here once or twice a year, but powerful sandstorms are not uncommon.

On the edge of the desert

The first Europeans to visit Al Nafud left a mesmerizing description of the region. “What is most striking about this desert is its colour,” wrote Lady Anne Blunt in 1878:

“It is not white like the sand dunes we passed yesterday, and not yellow like the sand in some parts of the Egyptian desert. but really bright red, almost crimson in the morning, when the dew has not yet dried. And it would be a big mistake to think that it is sterile. On the contrary, Al-Nafud is richer in forests and pastures than all the sands that we crossed when we left Damascus. Everywhere we met Ghada bushes and bushes of another type, which are called yerta here.”

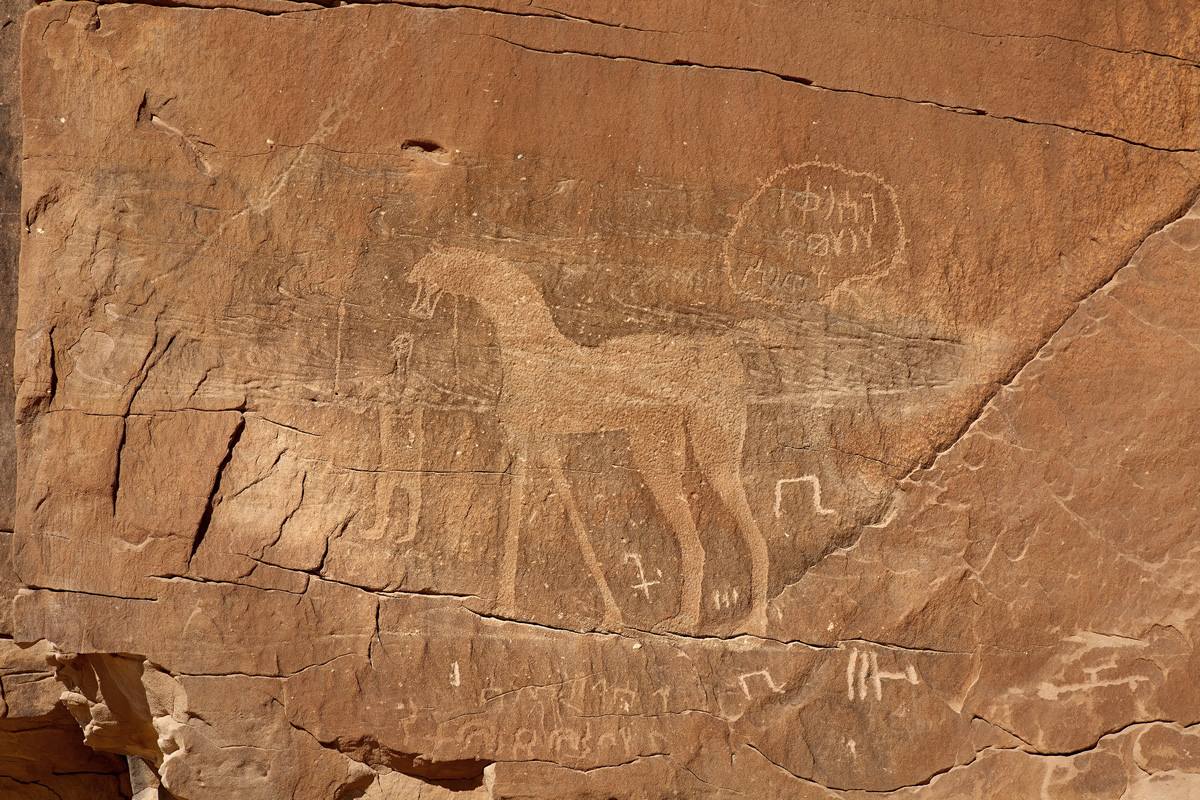

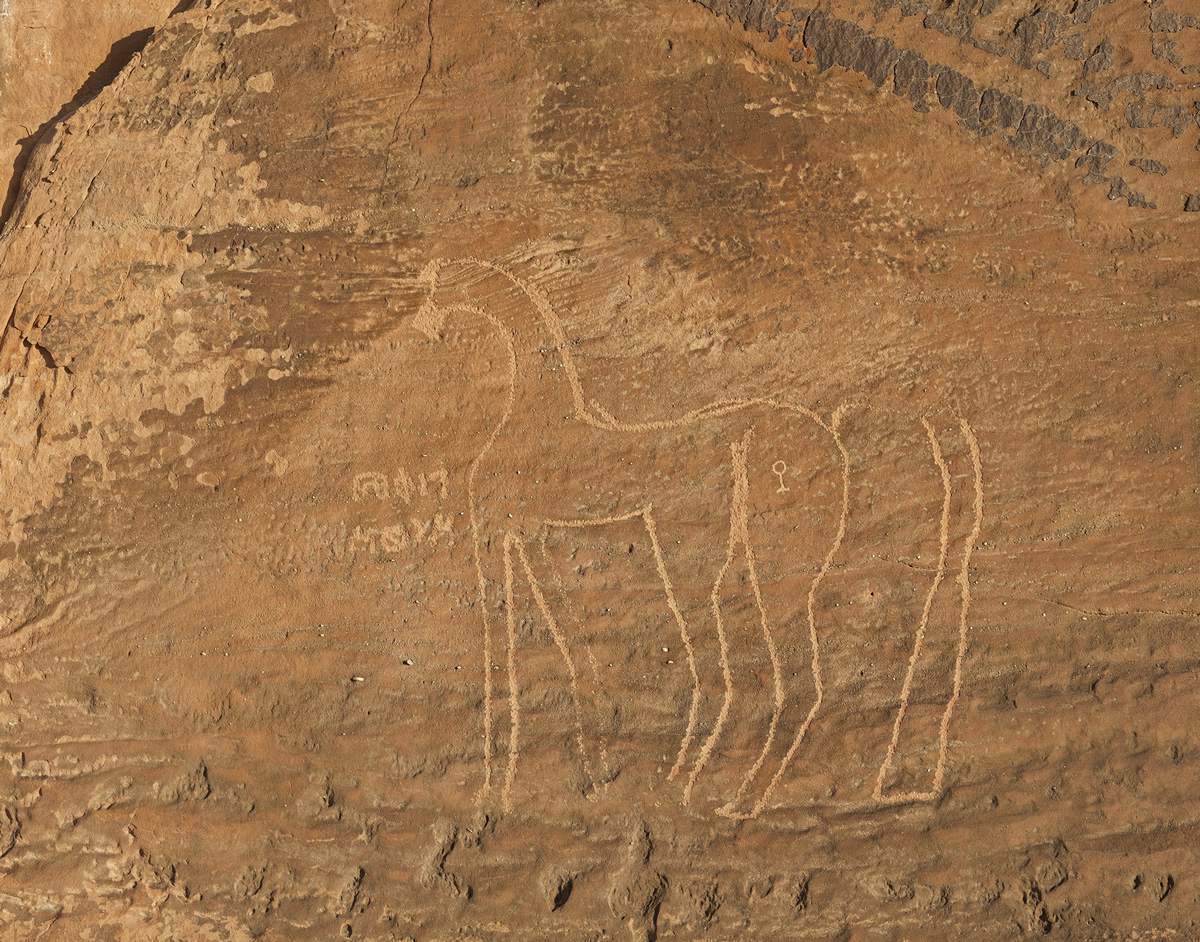

All Arabian deserts are covered with large tracts of lava fields formed during the eruption of ancient volcanoes. Here they are called harrats. The largest of them are Esh-Shama, Uvayrid, Ifnayn, Khaybar and Kura, Rakhat, Kishb, Hadan, Navasif, Bukum and Al-Birk. Harrat al-Uvayrid adjoins the Taima. It was first described by Charles Montague Doughty, a 19th-century explorer and author of Travels in the Arabian Desert. The rocks in this region are covered with numerous petroglyphs depicting people and animals, some of the images dates from the Neolithic era, some – to a relatively later time.

Older images appear darker and patinated, while younger images are lighter and more distinct. Ancient artists loved to depict shepherds with herds of sheep and goats, hunters with bows surrounded by dogs, animals such as ibex, bison, onager, gazelle. They painted people without facial features, but detailed headdresses and clothes. In the oldest drawings, there are no horses or camels, and, of course, no inscriptions.

But from the 3rd millennium BC, both horses and camels appear. Moreover, war chariots rush along the rocks, carts ride and the horses are distinguished by their graceful constitution and look like the famous Arabian breed of stallions. Dromedary camels follow the horses. And from about the 7th century BC, pictures are supplied with ancient Arabic letters. There are many such petroglyphs around the Taima oasis and in the oasis itself, where the ancient city was once located.

Rich Taima

The first images of Arabian horses were found here. Apparently, from here Arabian horses came to Egypt, and already in the 15th century BC, the cavalry of the pharaohs was formed from them. Since that time, rock scenes abound with pictures of battles with the participation of cavalry. The riders are equipped with straight swords with a clearly visible guard.

In ancient times, caravan routes went through the Tayma oasis. It was essentially a crossroad – on the right hand were Mesopotamia and the Red Sea, on the left – Egypt, to the south was the state of the Israelites, to the north lay the coast where the mysterious “sea peoples” were said to live. It is not surprising that the oasis has been inhabited since antiquity. A lot of archaeological evidence remains from this time. In 2010, for example, a rock with an inscription from the time of Pharaoh Ramses III (1186-1155 BC) was found here. Both the Bible and the texts of Assyria tell about Tayma. The Assyrians called Taimu Tiamat, and the Israelites called Tima.

In the 8th century BC, the ruler of Assyria, Tiglathpalasar III, imposed a tribute on Tayma, and his descendant Sinacherib ordered to bring gifts from the inhabitants of Tayma to its capital Nineveh through the Desert Gate. Probably, the inhabitants of the oasis, who could not resist the large states, preferred to buy off their enemies.

Fortunately, the city was rich, it was surrounded by walls, the remains of which archaeologists have found. Once again, Taimu was conquered by the Babylonian ruler Nabonidus, known for making the main god of the country not Marduk, but Sina, and began to build temples to the moon god throughout the land under his control. At the time, he settled for a whole decade, leaving the Babylonian throne to the son of Belshazzar. And the construction of the Sina temple in Tayma, probably, was not done without.

It is not surprising that the Israelites considered the inhabitants of Tayma to be pagans, and the prophet Jeremiah did not forget to stigmatize the luxury of these wicked. The petroglyphs on the Al-Naslaa rock probably belong to this time. The cliff depicts a horse of incredible beauty, which for some reason tourists take for a giraffe, and a man standing next to it. And above there is an ancient Arabic inscription, which has not yet been deciphered.

Rock cut in two

Tourists love to be photographed at the Al-Naslaa cliff. The horse, the man, and the indecipherable inscription do not interest them at all. Almost no one looks at the petroglyph.

On the other hand, all eyes are fixed on a perfectly flat and perfectly thin cut separating the right side of the stone from the left. Everyone is worried about only a few targeted questions: Who was able to cut this stone so cleverly exactly in the middle? How did they cut it? And for what? And why do ancient boulders stand on props that resemble a glass and do not fall? Who could place stones so ideally on these ledges that the entire structure would not fall apart over the millennia, but would stand unshakable?

Then, a lot of assumptions of the most incredible kind are being put forward. The most naive believe that this is the creation of the ancient gods or aliens.

True, they cannot explain why one or the other had to install the cut stone on a support. Others, more intellectually talk about forgotten technologies of the ancients and consider the rock to be a workpiece for some kind of building, which for some reason was not carried away by stone cutters. Still, others agreeing with the latter, think that this is an ancient monument erected in memory of some event.

Allegedly, the rock was sawn with copper tools, and then cleaned from the inside with a pumice stone. True, how it was possible for someone to wipe the irregularities of the cut with a copper saw in a very narrow space with a pumice stone without peeling off hand hands is completely incomprehensible. Sandstone and soft material, but hard work, and all the same – it will not work perfectly. This is where the forgotten technologies of the ancients come to the rescue, that’s why they are forgotten.

Geologists, however, look at these disputes with a grin. According to them, people did not lay hands on the Al-Naslaa rock. In fact, the unusual cut appeared for natural reasons. After all, there is a rock in a specific area, where the day is unbearably hot and the night is unbearably cold. Stones, if they have internal defects, as every engineer and builder who has studied the strength of materials know, expand in the heat and shrink in the cold. In the end, the defective structure breaks down and the stone bursts. As a rule, the crack looks perfectly flat.

Probably, the Al-Naslaa rock fell into two parts even in the deepest antiquity. And then the winds and water grinded it – millennia ago, when the climate in Arabia was rainier. Winds, weighed down by suspended sand in the air, are the best abrasive material for working on narrow cracks. Moreover, the wind, bursting into a narrow gap, accelerates, and the sand rubs the surface no worse than emery. If the wind is also saturated with moisture, you yourself understand what a great grinding tool it is!

So there is atleast one scientific explanation to the existence of the “cut” rock. But the actual secret here is completely different in the figure; and, of course, in the inscription. Who left it? What event was it connected with? Until the text is read, it is difficult to speculate.

Some archaeologists, to say, believe that the rock was an object of worship because in Arabia, the worship of stones was in the order of things. But it is unlikely that a petroglyph with a man and a horse would appear on the sacred stone. And even more so accompanied by text. But then what is it? So far, there is only one answer: we do not know.