Deep within the unforgiving Sahara Desert, whispers of a mythical city laden with gold and wealth echo through the sands of time, a city known as Zerzura. This elusive city, believed to be a grand oasis concealed by its ancient inhabitants, has piqued the interest of explorers and scholars alike for centuries. Could it be the ‘Saharan Atlantis’? Is there a connection between these two legendary cities? The quest to uncover these mysteries about Zerzura continues to fuel modern research and exploration.

The legend of Zerzura: tracing its origins

Arab geographers and travelers: the early accounts

The narrative of Zerzura can be traced as far back as the 13th century, when Arab geographers and travelers began to chronicle the city’s existence. These early accounts painted a picture of Zerzura as a stunning oasis city, resplendent with gold and precious gems. Its inhabitants, believed to be descendants of ancient Egyptians, supposedly concealed the city’s location to safeguard their wealth.

As the lore evolved, so did the portrayals of Zerzura. Some narrations speak of a city shielded by magic spells, while others describe a dormant king and his entourage guarding the city’s entrance. A few suggest that Zerzura lies buried beneath the desert sands, awaiting the right moment to rise again.

European exploration: the hunt for Zerzura

The allure of Zerzura captivated European explorers during the Age of Exploration. As they ventured into the African continent in the 19th century, the hunt for Zerzura became an obsession fueled by tales of other lost cities such as Atlantis and El Dorado.

One of the earliest European references to Zerzura dates back to 1843 in a publication titled “Modern Egypt and Thebes: Being a Description of Egypt” by renowned English Egyptologist, John Gardner Wilkinson. Wilkinson’s source was based on accounts from inhabitants of the Dakhla Oasis in Egypt who spoke of an unexplored oasis, abundant with palms and springs, with some ruins of an unidentified era.

“Five or six days west of the road to Farafreh is another Oasis, called Wadee Zerzoora [Zerzura], about the size of the Oasis Perva, abounding in palms, with springs, and some ruins of uncertain date. It was discovered about twenty years ago by an Arab, while in search of a stray camel and from seeing the footsteps of men and sheep, he supposed it to be inhabited.” – John Gardner Wilkinson

Despite the harsh desert conditions and local hostilities that led to several tragic expeditions, the allure of Zerzura remained strong, and its legend continued to flourish.

The mystical manuscript: Kitab al Kanuz

Another significant mention of Zerzura comes from Harding King’s “Mysteries of the Libyan Desert”, published in 1925. King references the Kitab al Kanuz, a lost medieval Arabic manuscript from the 15th century written by an anonymous author. The manuscript is believed to be a collection of mystical fables that list sites in Egypt that hold hidden treasures.

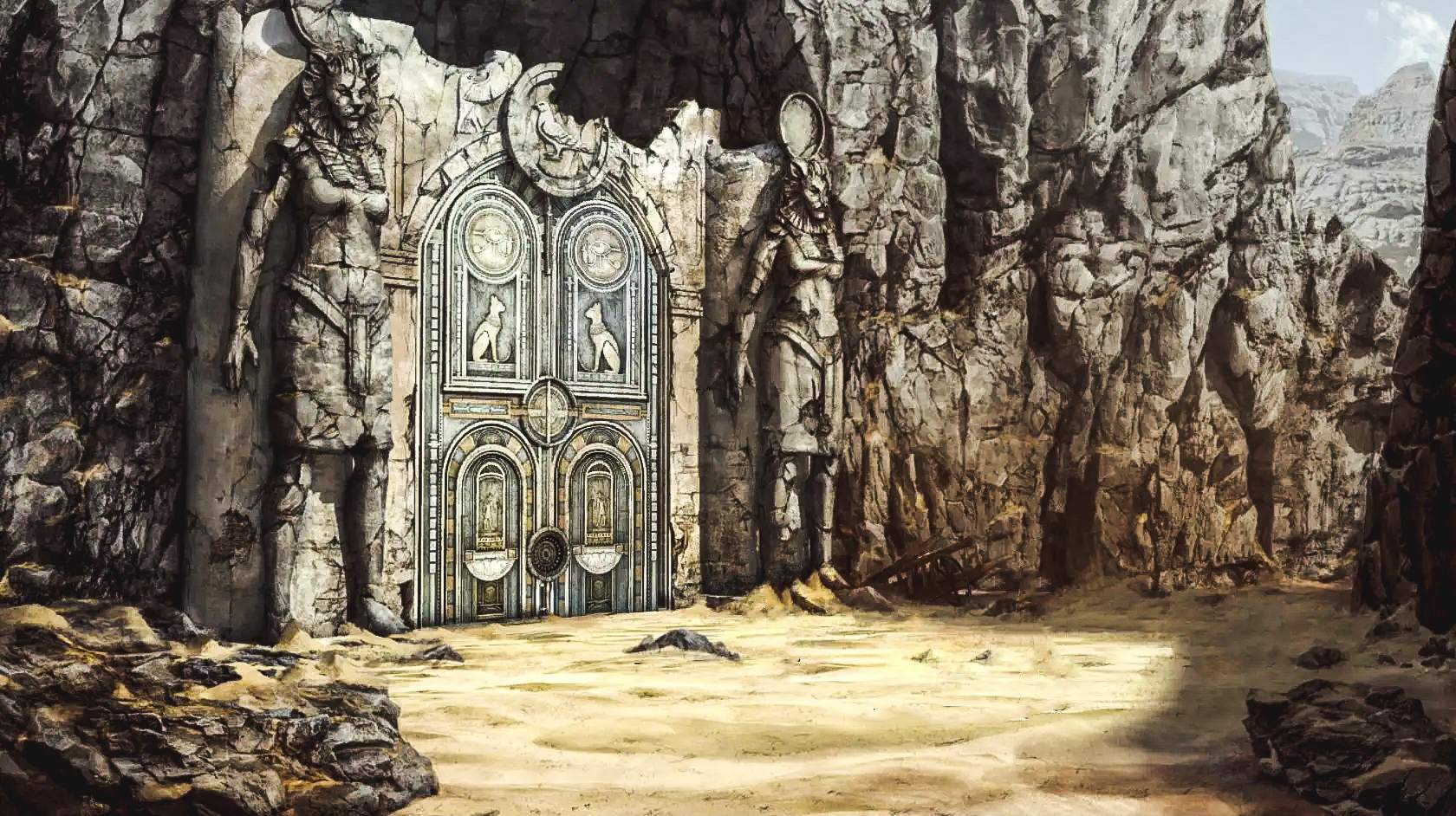

According to King, the manuscript describes the path leading to the city of Zerzura, adorned with palms, vines, and springs. The description provides a vivid picture of the city, painting it as a white city with a closed door, on which a bird is carved.

“In the city of Wardabaha, situated behind the citadel of el Suri, you will see palms, vines, and springs. Penetrate into the wadi and pursue you way up to it; you will find another wadi running westwards between two mountains. From this last wadi starts a road which will lead you to the city of Zerzura, of which you will find the door closed; this city is white like a pigeon, and on the door of it is carved a bird. Take with your hand the key in the beak of the bird, then open the door of the city. Enter, and there you will find great riches, also the king and queen sleeping in the castle. Do not approach them but take the treasure.” – Harding King’s citation from the Kitab al Kanuz

Historical controversies surrounding Zerzura’s existence

Despite the historical references and the manuscript’s description, controversies about Zerzura’s existence have always been prevalent. In 1928, Dr. John Ball refuted King’s association of the Kitab al Kanuz with Zerzura and instead pointed towards a manuscript written by Syrian emir Osman el Nabulsi in AD 1447.

El Nabulsi’s manuscript portrayed Zerzura as one of several deserted villages of his time, situated near a canal called the Bahr Tanabtawayh. This contradicted the description of a thriving oasis city in the earlier references.

A. Johnson Pasha weighs in on the argument by submitting a paper in 1930 simply titled, “Zerzura”. Pasha was a member of the Royal Geographical Society and claimed to have a copy of the Kitab al Kanuz which he loaned to the Department of Antiquities for translation.

Pasha writes: “I see that an ingenious suggestion has been made that the tradition of Zerzura started with the inclusion of a village bearing the same name in a list of deserted villages on the north-western border of the Faiyum, written two hundred years earlier than the Kitab al Kanuz. I think that this, though ingenious in the way of controversy, cannot be taken seriously when we are attempting to get a lead as to existence of the traditional Zerzura from actual facts.”

“When I first went to Dakhla (1885-6) I was supposed to be the first high official who had visited the oasis since “the killing,” which I understand was about the time of Muhammad ‘Ali. They spoke a good deal of the oasis of the blacks which they distinguished clearly from Zerzura. They spoke of a Mameluke Bey who had been sent to stop the raids by the blacks and of his having poisoned the water supply that the blacks depended on before they got to Dakhla. They asserted that a man who had been lost in the desert and been saved by reaching Zerzura had died in Dakhla only a few years before. Their idea of Zerzura was a fairly large oasis with many trees, springs, grass, and ruins, and they always dwelt on wild cattle,” added Pasha.

The pursuit of Zerzura: László Almásy’s expedition

The allure of Zerzura’s legend caught the interest of Hungarian desert explorer and aviator László Almásy. Almásy, who inspired the protagonist in Michael Ondaatje’s novel “The English Patient”, became captivated with the stories and lore of Zerzura.

After extensive research and interviews with native Bedouins, Almásy concluded that Zerzura should be somewhere in the unexplored Gilf Kebir region, near the end of the route from the Dachla Oasis to the Kufra Oasis. His expedition in 1932 led to the discovery of Wadi Talh, supposedly one of the three valleys of Zerzura.

The other two valleys were discovered by the expedition of Patrick Clayton and Lady Clayton, and by an air reconnaissance survey conducted by Almásy’s colleagues.

Whether this is the Zerzura from legend is inconclusive. Just prior to the Almásy expedition, Ralph Alger Bagnold, a desert explorer, geologist and soldier, was exploring the region after reading Ahmed Hassanein’s “Lost Oasis”.

After reading a paper on Almásy’s expedition, Bagnold wrote: “I shall continue to think that Zerzura is one of the many names that have been given to the many fabulous cities which the great North African desert has for ages created in the minds of those to whom it was hardly accessible; and that to identify Zerzura with any one discovery is but to particularise the general.”

“There can be little doubt that the wadis in the Gilf Kebir are the truth behind the Egyptian legends of the Oasis of the Blacks [Zerzura]. The actual waterhole has not yet been found, but it most probably will be when next the wadi is visited. Almásy deserves very great credit for his persistence in following up the problem of Wilkinson’s oasis and for the success of his efforts,” added Bagnold.

Modern research and theories

Archaeological evidence

Some archaeologists propose that Zerzura may be a combination of several ancient settlements lost to the sands of time. As the Sahara Desert expanded due to climate changes, these prosperous settlements might have been abandoned, their remnants gradually buried under shifting sands.

Significant discoveries in the region support the notion that the Sahara once supported complex societies. The Nabta Playa ceremonial site in modern-day Egypt, dating back to about 7000 BCE, suggests that advanced cultures existed in the area even before the rise of the Egyptian civilization. Additionally, the Garamantes civilization, which flourished in the Libyan part of the Sahara between 500 BCE and 700 CE, exemplifies that complex urban centers could thrive in this challenging environment.

Satellite imagery

Advancements in technology have provided researchers with new tools in the quest for Zerzura. Satellite imagery has revealed ancient riverbeds and potential settlement sites in the Sahara, suggesting that the region may have once supported thriving communities.

Theories regarding Zerzura’s location

Southern reaches of the Sahara?

The potential location of Zerzura has sparked several theories. Some researchers believe it may be found in the western desert of Egypt, others suggest Libya or Chad, and yet others propose that Zerzura might have been located in the southern reaches of the Sahara, in areas now part of Niger or Mali.

Map of the Hermit

Among the theories, one of the most intriguing is based on the discovery of an ancient map known as the “Map of the Hermit,” dating back to the 15th century. This map depicts a fortified city in the heart of the Sahara Desert, surrounded by mountains and palm trees. Some researchers postulate that this city could be Zerzura, though the map’s authenticity and accuracy have been questioned.

The ongoing quest for Zerzura

Despite the absence of concrete evidence, the search for Zerzura continues to fascinate researchers and enthusiasts. Expeditions into the Sahara continue in hopes of uncovering this legendary city or at least finding traces of the ancient civilizations that may have inspired the myth.

Modern technology, like satellite imagery, ground-penetrating radar, and LiDAR, has significantly improved researchers’ ability to explore and map the vast desert landscape. Furthermore, the study of ancient texts, oral histories, and local folklore remains crucial in piecing together the puzzle of Zerzura.

By combining traditional sources of information with cutting-edge technologies, researchers hope to one day unravel the truth behind this enigmatic lost city.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the existence of Zerzura remains unconfirmed, the persistent search for the city has led to valuable discoveries about the ancient civilizations that once inhabited the Sahara. With the continued development of technology and the dedication of researchers and explorers, the mysteries surrounding Zerzura may eventually be unraveled, shedding light on the rich and complex history of the Sahara Desert and its people. For now, it remains as the Sahara’s hidden jewel.