The title of a story published on November 14th, 2017 in Epoch Times claimed a genuinely astonishing discovery: “Australian Aboriginal symbols discovered on mysterious 12,000-year-old pillar in Turkey.” This surprising news is once again circulating these days. So, is it possible that Aboriginal Australians had a secret connection with the Göbekli Tepe?

To say, this outlandish idea was based on superficial parallels between pictures and symbols found in both cultural environments (Anatolian Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe and Aboriginal Australia).

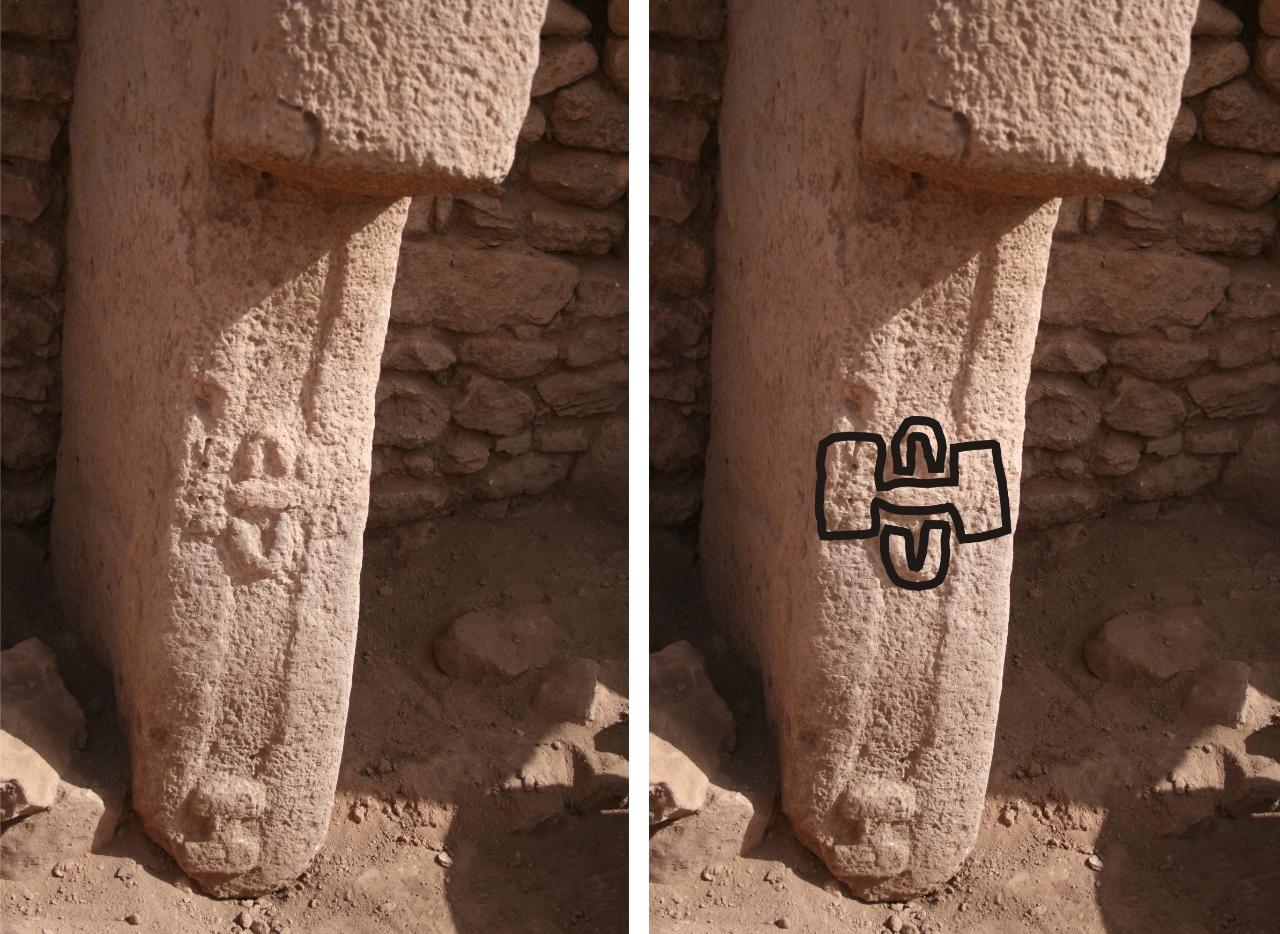

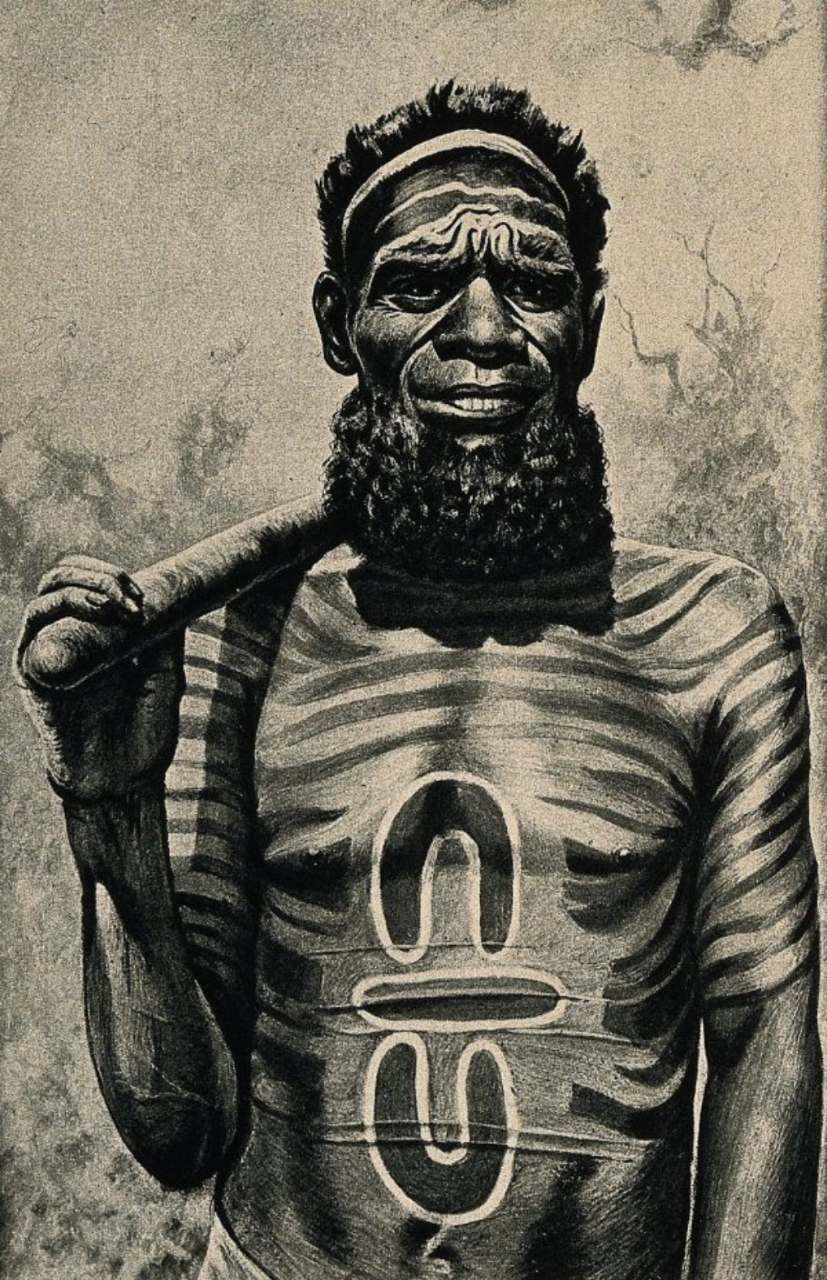

Aboriginal sign which appears to have been painted onto a medicine man’s chest is paralleled with symbols carved into stones on Göbekli Tepe’s pillars or other artifacts known from this and other contemporaneous sites in the vicinity.

According to the most recent studies, the Australian continent was most likely colonized around 65,000 years ago, most likely via the Malay archipelago. So, at some time, both cultures were contemporaneous? Yes, but in different corners of the world, separated by an ocean.

And, in the case of the Australians, with an extraordinarily long period of isolation. Because of the evident historical gap and the large geographical distance of around 15,000 kilometers, a direct relationship and interaction of both cultural events would be impossible.

The primary evidence, the Aboriginal elder’s chest sign, on the other hand, is considerably younger. The image in question appears to be a replica of a shot from the late nineteenth/early twentieth century Spencer and Gillen’s anthropological explorations throughout the continent.

The initial image was published in 1904 (Spencer & Gillen 1904, 58 Fig. 33) – far later, around 12,000 years later, than the Göbekli Tepe pillar was carved. Once again, quite a distance.

Nonetheless, the relatively new study of Aboriginal symbolism helps us to grasp the image in question here, which depicts two people talking. The alleged parallel at Göbekli Tepe, on the other hand, is a far uncommon outlier in early Neolithic iconography — one of which we cannot say what it truly meant to the prehistoric people carving it owing to a dearth of relevant materials.

Furthermore, and this may be the most important point to emphasize here, the Göbekli Tepe sign does not seem precisely the same. In reality, upon closer observation (see Fig. 2), what seems to be a straight horizontal line in the Aboriginal sign is actually a “H”-shaped emblem on the T-Pillar — with two vertical ‘arms’ on either side (which are obviously missing in the Australian example).

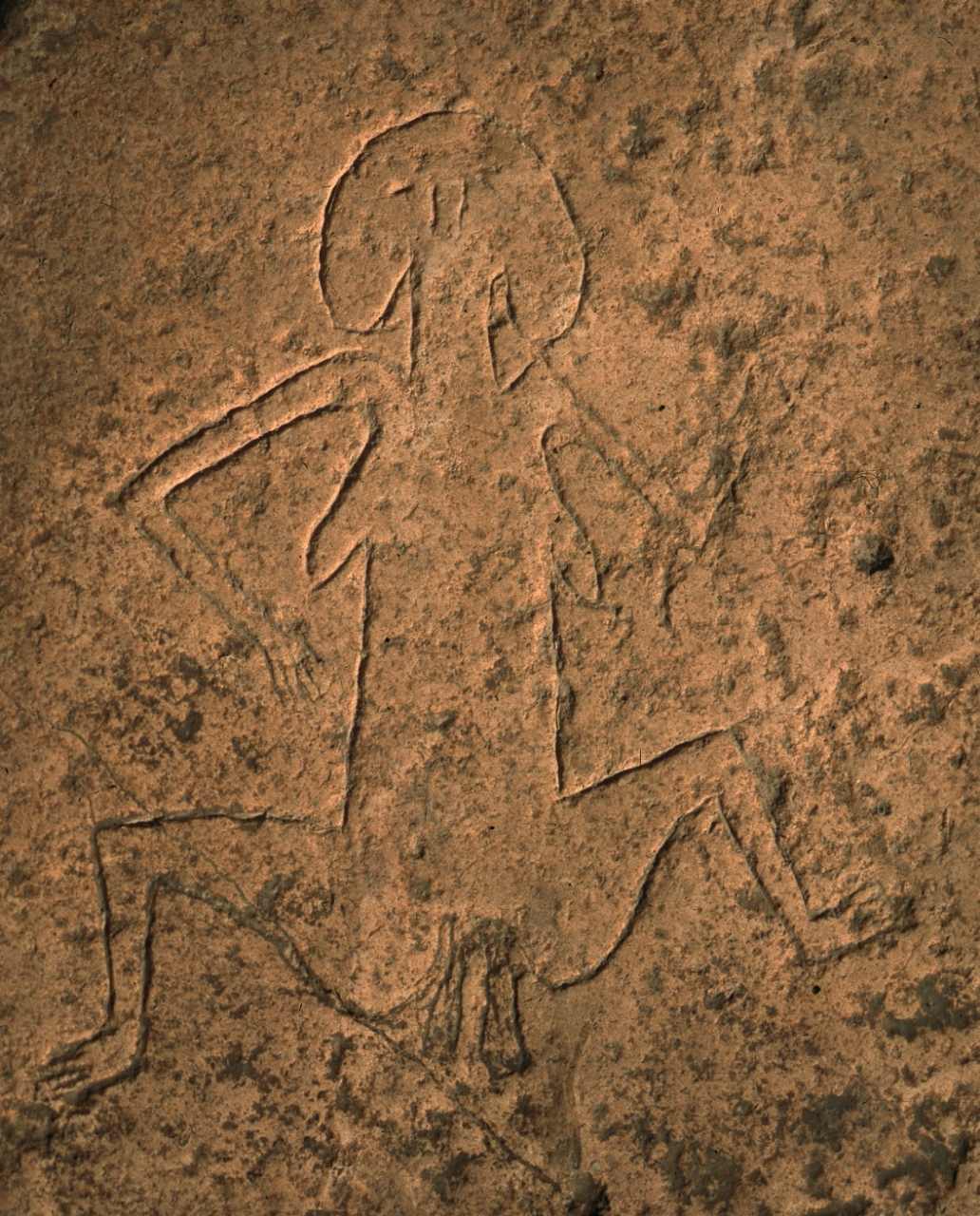

The same may be argued for the other symbols listed, particularly the female figure from Göbekli Tepe’s so-called Lion’s Pillar Building, which is related to Aboriginal images of the Rainbow Serpent, known as Yingarna in certain Aboriginal tribes and sometimes represented as a woman.

Again, we have context and meaning for one of these (the Australian example), but no further sources for the other at Göbekli Tepe – which, by the way, was not part of the original ornamentation, but is a later added (and unusual) graffito.

These already problematic parallels are muddled further by assumptions intended to emphasize the argument but without a clear factual basis. Substantiating that the Göbekli Tepe pillar symbols must be “similarly sacred” since the “pillar symbolizes a god” is, of course, fascinating, but not without complications, as previously mentioned.

The claim that the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe were “… constructed by a society that was wiped out by a cataclysmic disaster,” reference to a recently released research that caused a comparable news flow, was also criticized.

In the end, an all-too-simple identification of similarly seeming symbols and equating of the complex individual cultural processes behind them is extremely speculative — and does both civilizations and their rich iconography a disservice.

Furthermore, the selection of only a few images and symbols from an otherwise vast (and diverse) iconographic repertoire appears random. There are many more contrasts than parallels between these two civilizations and locations.

In addition, Aboriginal Australians do not create a single homogeneous culture complex. Meanwhile, over 400 unique Australian Aboriginal peoples may have been found, each with their own language (including a particular symbolic language) and culture (Horton 1994).

So, in response to the question stated in the headline: No. No, Aboriginal Australians did not construct Göbekli Tepe. The apparent parallels in iconography and art are remarkable coincidences at best, and misinterpretations at worst.

According to the same logic, the early Neolithic hunter-gatherers of Göbekli Tepe invented the letter “T” owing to the distinctive shape of these ubiquitous pillars…