Cremation is a common method that has been around for thousands of years and is still widely used in many parts of the world as a way to dispose of human remains. But have you ever given any thought to when and where the practice of cremation first came into existence?

According to a breakthrough study, the earliest known cremation in the Near East goes back to 7,000 BC. This astounding discovery sheds light on a crucial shift that took place in the burial practices of ancient civilizations and provides new insight into the beliefs and practices of ancient cultures.

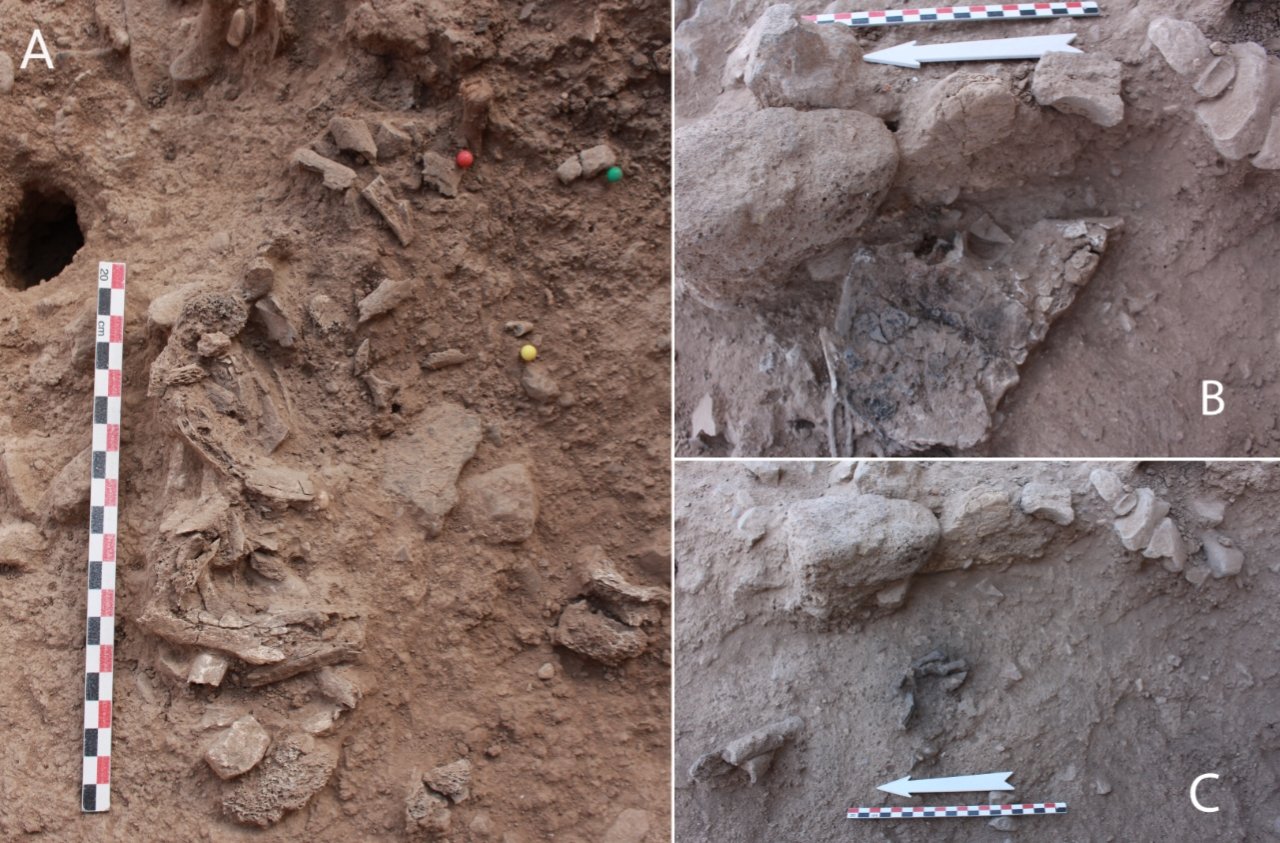

While excavating the Neolithic settlement of Beisamoun in the Upper Jordan Valley of northern Israel in 2013, researchers discovered the unusual burial site. According to the lead researcher of the study, Fanny Bocquentin, the burial hole had a total of 355 bone pieces, the majority of which had been burnt.

According to the study published online on August 12, 2020, in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Fanny Bocquentin of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and colleagues, ancient people in the Near East had begun the practice of intentionally cremating their dead by the beginning of the 7th millennium BC.

Excavations at the Neolithic site of Beisamoun in Northern Israel have revealed an ancient cremation pit containing the bones of a corpse that appears to have been intentionally burned as part of a funeral practice. These bones were directly dated to between 7,031 and 6,700 BC, (during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic C culture) making them the Near East’s oldest known case of cremation.

The remains are mostly of a young adult’s skeleton but their sex and height remain a mystery (the remaining bones were too damaged to tell, the lead researcher Fanny Bocquentin said). The bones exhibit signs of having been roasted to temperatures beyond 500°C shortly after death, and they are housed in a pit with an open top and strong insulating walls.

The microscopic plant fragments discovered inside the pyre pit are most likely leftovers from the fire’s fuel. This evidence leads the authors to believe that this was a deliberate cremation of a fresh corpse, rather than the burning of dried bones or an unfortunate fire accident.

This early cremation arrives at a critical juncture in funeral practices in this part of the world. Old customs, such as removing the dead’s skull and burying the dead within the community, were dying away, while new practices, such as cremation, were emerging. This shift in funeral practice may also indicate a shift in the rituals around death and the status of the departed within society. Further examination of other common cremation sites in the area will be helpful in explaining this important cultural transition.

Bocquentin says: “The funerary treatment involved in situ cremation within a pyre-pit of a young adult individual who previously survived from a flint projectile injury – the inventory of bones and their relative position strongly supports the deposit of an articulated corpse and not dislocated bones.” She adds, “This is a redefinition of the place of the dead in the village and in society.”

In conclusion, the study by Fanny Boquentin provides an interesting insight into the ancient practice of cremation in the Near East. As we continue to learn about ancient civilizations, we gain a greater appreciation for the rich history of our world and the ways in which our ancestors lived and died. This study serves as a fascinating glimpse into the past and a reminder of the complexity of our human history.

With further research, we can gain a deeper understanding of the evolution of human customs and traditions, and how they have shaped our societies and beliefs throughout history. This study is just one example of the crucial work being done to uncover the mysteries of our past.