The Castle of Edinburgh is lying on a prehistoric site dating back to the Iron Age and prevailed over the skyline of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland. Many people believe it to be the most haunted city on Earth. If we go back to its history, we can find the castle has seen uncountable gruesome tortures, bloody battles and deaths during its time.

In the present day, the castle is used as a great tourist destination. But, visitors and staff often claim to have experienced the feeling of being touched and pulled when no one is around within the castle premises. Some of them also report having seen strange apparitions inside the castle hall.

Spirits that have been witnessed repeatedly including: an old man in the apron, a beheaded drummer boy, and a piper who once mysteriously ended his life after getting lost inside the tunnels underneath the castle.

However, behind this haunted Castle Rock, there is another cursed place that hides some of the European history’s darkest pasts in its soils. The place is widely known as the Nor’ Loch.

The Nor’ Loch ― A Dark Past Behind The Edinburgh Castle:

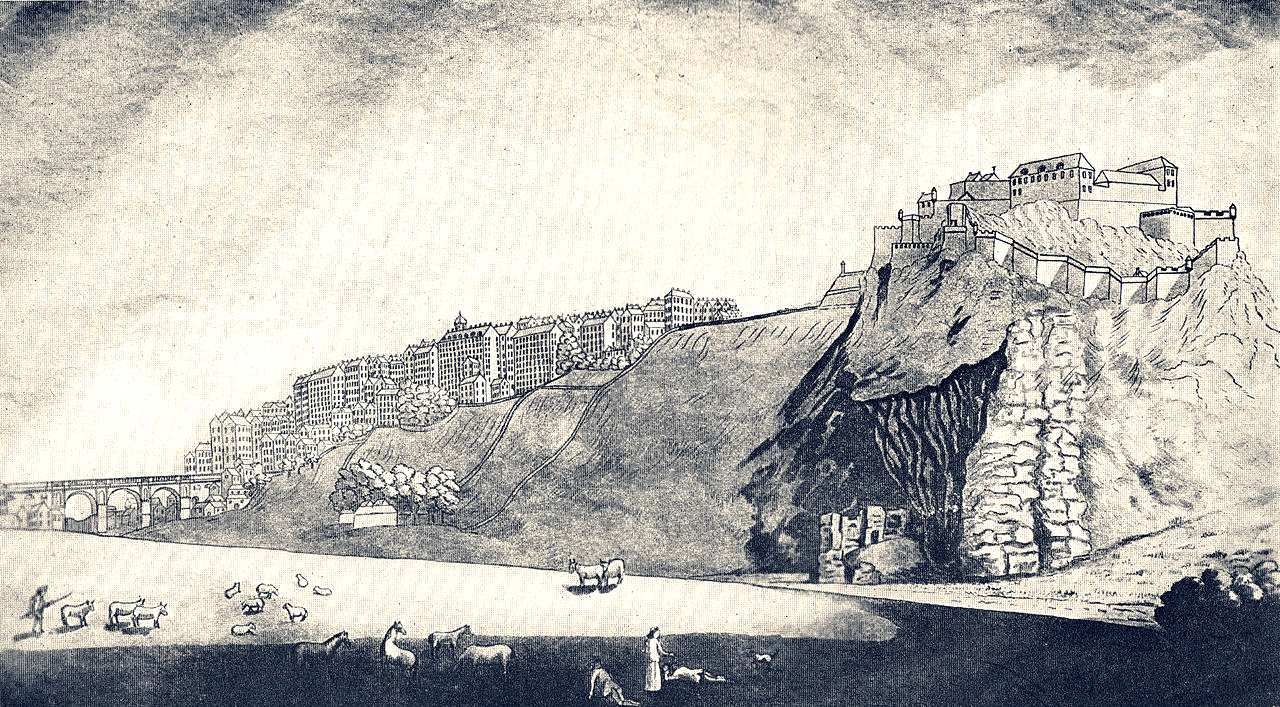

The Nor Loch, also known as the Nor’ Loch and the North Loch, was a lake formerly in Edinburgh, Scotland, in the area now occupied by Princes Street Gardens, which lies between the famous Royal Mile street and Princes Street.

The History Of The Nor’ Loch:

The precise origins of the Nor’ Loch are much contested. There is evidence to suggest that a large body of water existed in the valley to the north of the Castle Rock as far back as 15,000 years ago – the deep valley being a product of the last ice age.

However, at some point it appears the loch must have receded or vanished entirely, as there is no firm mention of it until the late 14th century, at which time the town of Edinburgh had already been in existence for several hundred years.

Therefore, the most widely-accepted belief is that the loch was man-made. Evidence suggests that it was created on the orders of King James II, around the middle of the 15th century, in order to bolster the town’s defences from the ever-present threat of invasion.

Scotland, and particularly Edinburgh, suffered frequent English invasions during the period of intermittent Anglo-Scottish wars from the 13th to 16th centuries.

Whatever the case, the loch, which extended from the Castle Rock down to the line of present-day Market Street, would certainly have provided the inhabitants of Edinburgh with added protection during the late Middle Ages.

As the Old Town became ever more crowded during the Middle Ages, the Nor Loch became similarly polluted, by sewage, household waste, and general detritus thrown down the hillside. All manner of effluent imaginable, including waste matter from the town’s many slaughterhouses, is said to have met with the loch’s stagnant waters. Therefore, historians are divided on whether the loch was ever used for drinking water.

Besides being a dumping ground and an important part of the city’s defence system the Nor’ Loch fulfilled a variety of other dark roles during this period:

Suicides:

Prince Street Gardens was once the site of the Nor’ Loch which was a common spot for suicide attempts.

Crimes:

The loch appears to have been used as a smuggling route and it witnessed numerous violent murders during the period.

Executions And Witch Trials:

It’s a popular legend that the Nor’ Loch was the site of ‘witch ducking’ in Edinburgh. ‘Witch ducking’ or ‘the swimming test’ was employed by witchcraft prosecutors in some areas of Europe as a method of identifying whether or not a suspect was guilty of witchcraft.

Executions and public trials were common things, with huge crowds gathering to witness the event. One of the more gruesome tales involved a Mr Sinclair and his two sisters who were sentenced to death for incest in 1628.

The story goes that the accused were locked in a chest with holes drilled in it and dumped in the loch. Two centuries later in the spring of 1820, when workers were busy digging a drain during the creation of West Princes Street Gardens, a large box containing the remains of three people was discovered deeply embedded in the mud.

The Witches’ Well commemorates the Scottish women who were accused of witchcraft and murdered between the 15th and 18th centuries. Though this ‘satanic panic’ was widespread across Europe, Scotland has the dubious honour of having executed the most people under this charge. This is in large part due to King James VI of Scotland’s famous hatred and obsession with the dark arts: he decreed that anyone suspected of being a witch must be in league with the Devil himself, and thus must be put to death.

This hysteria around witches, however, led to mass miscarriages of justice. Those accused of witchcraft never received a fair trial, and usually only admitted their guilt once they were subjected to horrific torture.

One of the most famous cases was the North Berwick Witch Trials, wherein James VI, upon returning to Scotland after collecting his new bride from Denmark, encountered storms so terrible that his ship had to turn back. He became convinced that the storms were the work of witches in North Berwick, at the time a small, insignificant village on the Scottish coast. Around 70 women were accused of being witches or their accomplices, and were subsequently either hung or burned at the stake.

In truth, the women accused of being witches were usually skilled herbalists, suffering from mental illness or had simply incurred someone’s grudge.

Prior to the Scottish Enlightenment, it is estimated that more than 300 people (mostly women) were sentenced to be tried for wizardry and witchcraft either in the Nor’ Loch itself or around its banks. The process was barbaric with victims being tied up thumb-to-toe, dragged down the muddy slope towards the loch and thrown into the water like rats. It’s called “Trial by Water.”

If they drowned and perished then they were declared innocent, but if they survived, they were ‘proven’ to be witches and killed. Death was guaranteed either way. However, in 1685 the law of Scotland outlawed drowning as a form of execution. But before then many lives were already taken.

Draining Of The Nor’ Loch And The City Renovation:

Draining of the Nor Loch began at the eastern end to allow construction of the North Bridge. Draining of the western end was undertaken between 1813 and 1820, under supervision by the engineer James Jardine to enable the creation of Princes Street Gardens. For several decades after draining of the Loch began, townspeople continued to refer to the area as the Nor Loch.

Later in the late 19th-century, the famed social reformer and urban planner Sir Patrick Geddes was improving the conditions of slums in Edinburgh’s Old Town by remodelling many of its narrow streets and closes, thus improving sunlight and airflow. He commissioned his friend and artist John Duncan to design a public drinking fountain near the castle in 1894 to commemorate the women who were senselessly persecuted for witchcraft.

Final Words:

Although the Nor Loch was filled in during the 19th-century, neither its legacy nor its name are entirely forgotten. During the construction of Waverley Station and the railway lines through the area, a number of bones were uncovered. Princes Street Gardens were created in the 1820s and now occupy much of the loch’s former extent. If you ever have a chance to visit this beautiful city, you must visit this historic site and feel the time it has left behind.