New Zealand’s ancient past is filled with mystery and intrigue. The remote island home to the Maori is also home to over 170 species of birds, of which over 80% are endemic, means they no longer exist anywhere else in the world. And many of the species are now extinct. The extinction of those birds is largely attributed to human settlement and to the many invasive species that came with it.

However, there are still some remnants of these unique creatures from a bygone era. This discovery of a 3,300-year-old unusually massive bird claw from New Zealand is a small but important reminder of how fragile life on earth can be.

More than three decades ago in 1987, the members of the New Zealand Speleological made a strange yet fascinating discovery. They were traversing the cave systems of Mount Owen in New Zealand when they unearthed a breathtaking find — a claw that seemed to have belonged to a dinosaur. And much to their surprise, it still had muscles and skin tissues attached to it.

Later, they found out that the mysterious talon had belonged to an extinct flightless bird species called moa. Native to New Zealand, moas, unfortunately, had become extinct approximately 700 to 800 years ago.

So, archaeologists have then posited that the mummified moa claw must have been over 3,300 years old upon discovery! It is estimated that the Moas’ ancestry can be traced back to the ancient supercontinent Gondwana around 80 million years ago.

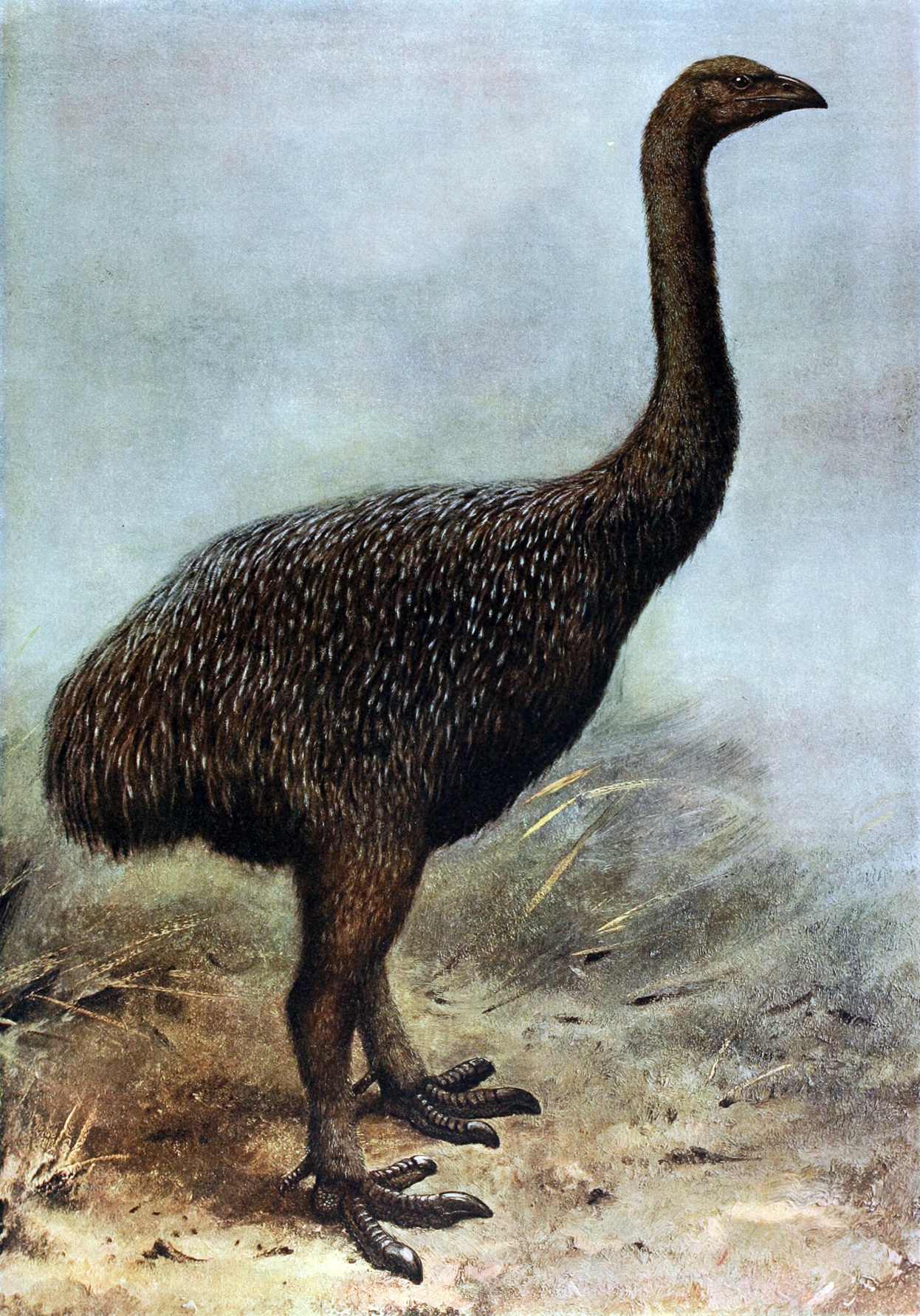

The name “moa” originates from the Polynesian word meaning domestic fowl, and the term refers to a group of birds that includes three families, six genera, and nine species.

The sizes of these species ranged widely; some were about the same size as a turkey, while others were considerably larger than an ostrich. The two largest of the nine species stood around 12 feet (3.6 m) tall and weighed roughly 510 lb (230 kg).

The fossil record shows that the extinct birds were predominantly herbivores; their diet consisted primarily of fruits, grass, leaves, and seeds. According to genetic analyses, the South American tinamous (a flying bird that is a sister group to ratites) were their closest living relatives. However, the nine species of moa, in contrast to all other ratites, were the only flightless birds that lacked vestigial wings.

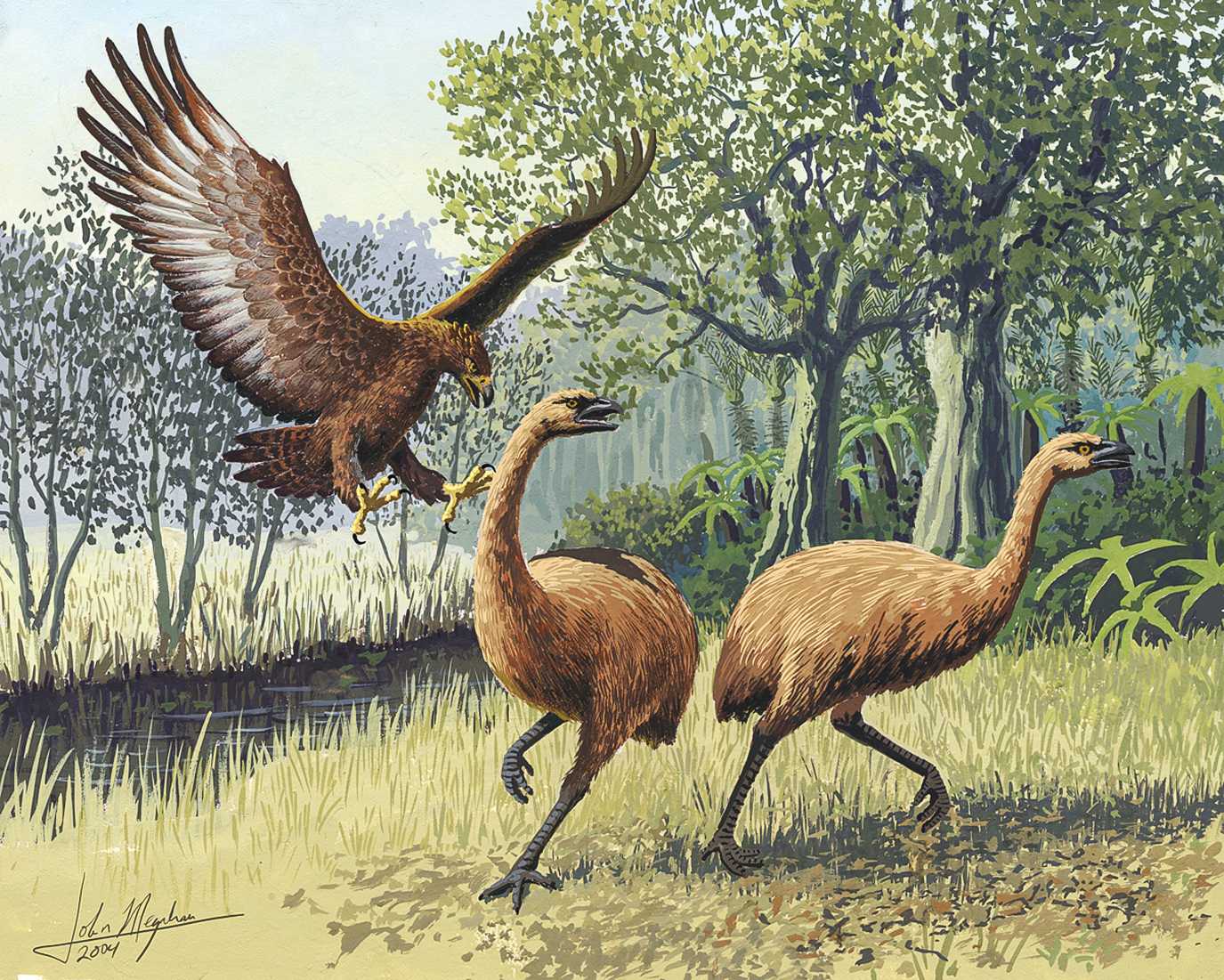

Moas used to be the largest terrestrial animals and herbivores that dominated the forests of New Zealand. The Haast’s eagle was its only natural predator before humans arrived.

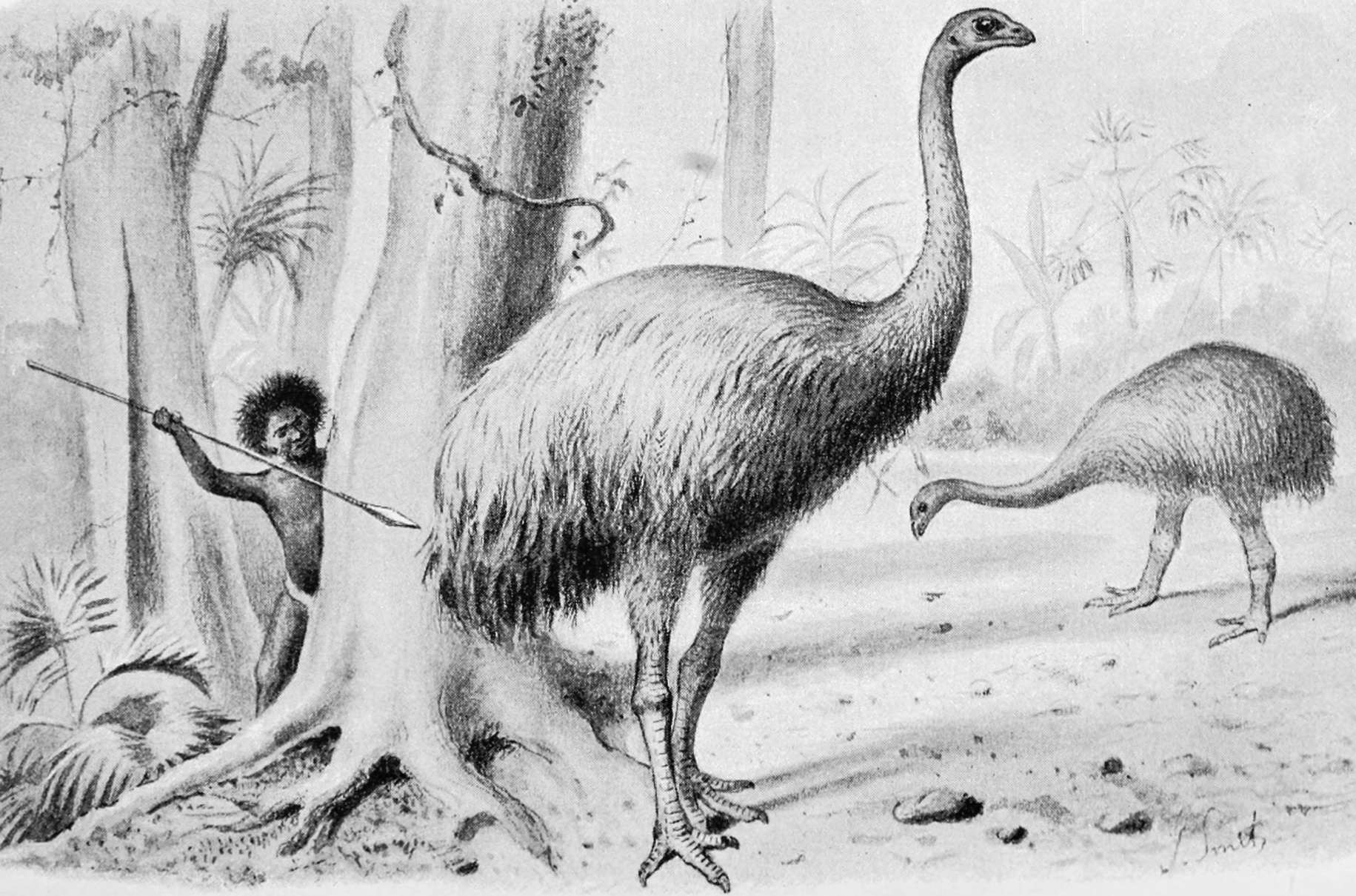

Meanwhile, the Maori and other Polynesians began arriving in the region in the early 1300s. Unfortunately, not long after humans arrived on the island, they went extinct and were never seen again. The Haast’s eagle also went extinct shortly after.

Numerous scientists asserted that hunting and habitat reduction were the main causes of their extinction. Trevor Worthy, a paleozoologist known for his extensive research on moa, appears to have agreed with this assumption.

“The inescapable conclusion is these birds were not senescent, not in the old age of their lineage and about to exit from the world. Rather they were robust, healthy populations when humans encountered and terminated them.”

Whatever the reasons were for the extinction of these species, may they serve as a warning to us to preserve the surviving species in peril.