Many times religion (of any sign) has opted to annihilate knowledge. For, voluntarily, putting an end to the progress of humanity for fear of losing the power of influence. At times, this destruction of knowledge has been able to cause it unintentionally, without knowing what it was doing. For an oversight.

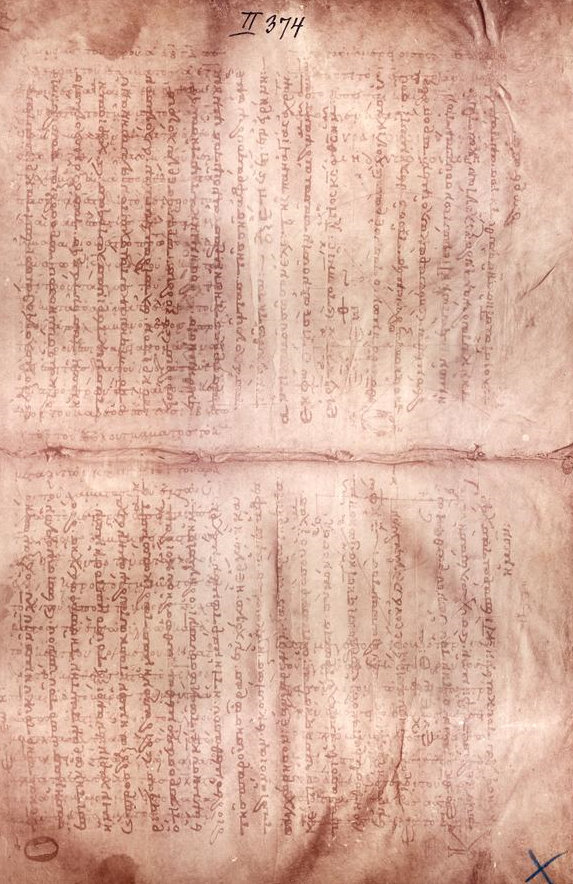

That is at least the moral we get from knowing what happened to the Archimedean Palimpsest. This essential unique document had among its pages The method of mechanical theorems of Archimedes, a famous mathematician of the time, as well as physicist and engineer, who lived developing his research in Syracuse in the second century BC.

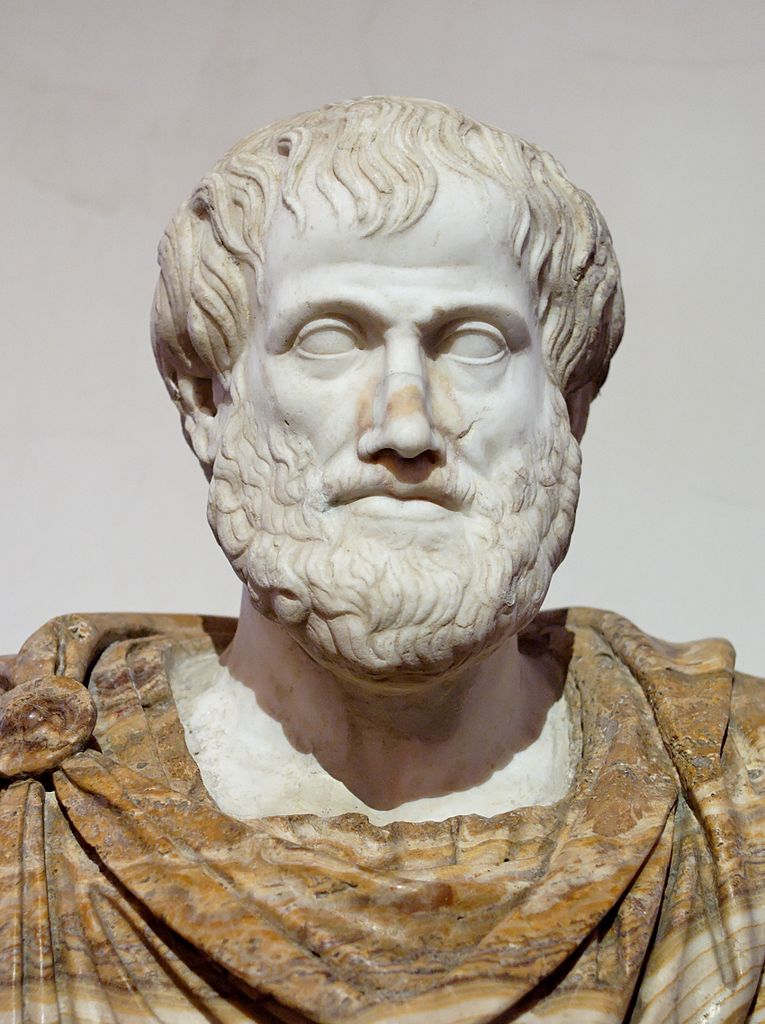

The document is found in Constantinople in the 10th century. It contained, to our knowledge, a speech by a famous 4th century BC Athenian politician and orator named Hyperides; a comment on a work by Aristotle, from the 3rd century; and, above all, approximations and calculations that anticipated our modern mathematics twenty centuries, including combinatorial mathematics.

What humanity would not discover with the development of mathematics until the arrival of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz in the early seventeenth century, this ancient thinker had already formulated.

In particular, he found a way to calculate the centre of gravity of a parallelogram, a triangle, and a trapezoid; and to calculate the centre of gravity of a parabola segment. These types of calculations, although very primitive, are those that, advanced the theoretical development, later allow us to deduce problems such as those of “how long it took a car to travel from point A to point B”. To accurately calculate the expenses of a company. To have road safety. To firmly build macro-bridges or skyscrapers.

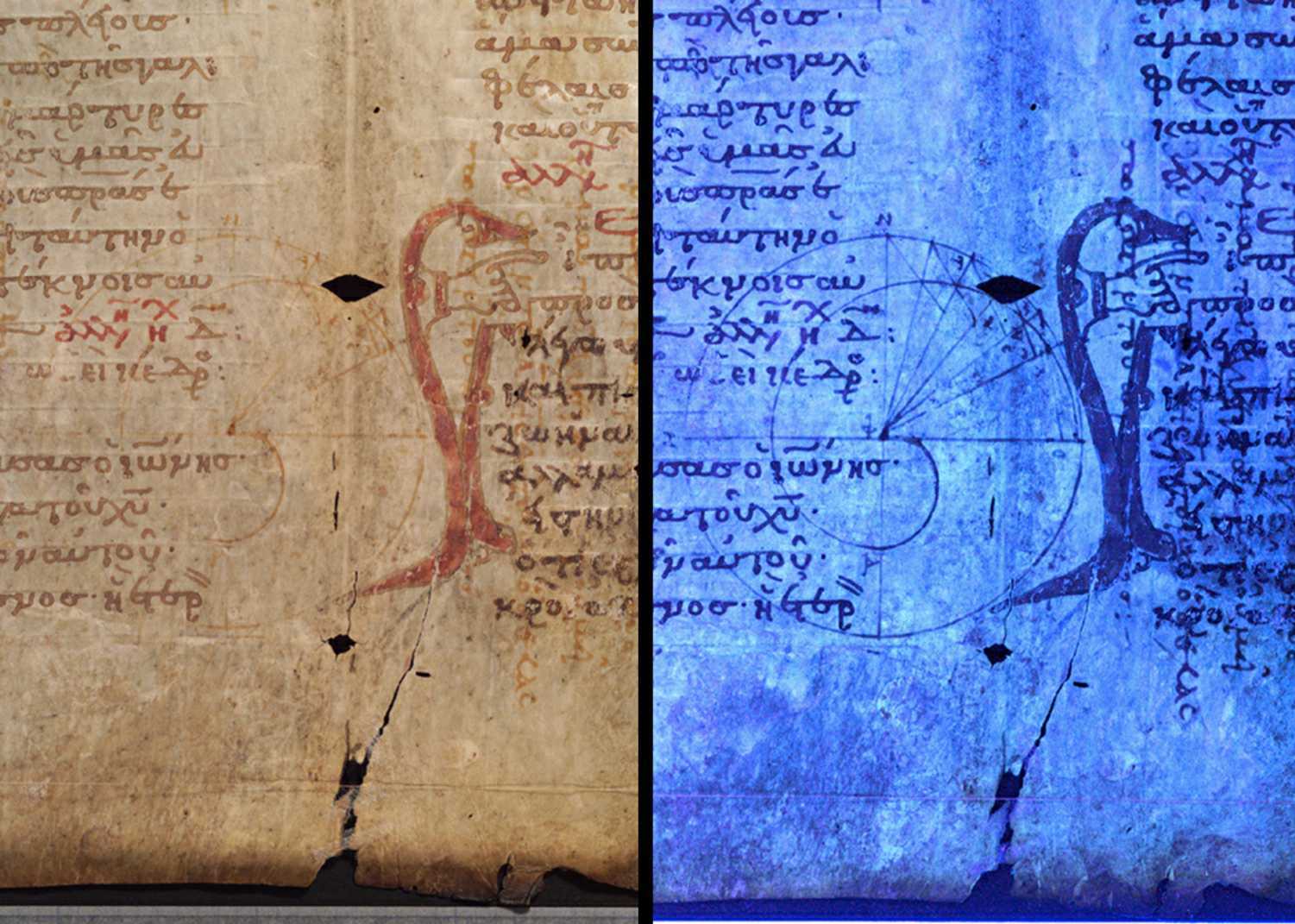

And what happened then? That no one seemed to understand at the time the importance of his revelations. The parchment, as we say, lived a long journey for 12 centuries, until three centuries later it was taken by monks from a Christian convent. They peeled the document, scratched imperfectly what its pages said, and combined the pages, split in half, with those of six other books that were there.

They recycled and re-pressed the pages and wrote a book of psalms and Christian prayers on them. It was a common practice at the time since the paper was a luxury. It’s just that they decided to downplay what Archimedes had written and prioritize some of his songs.

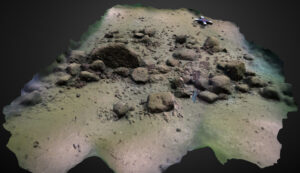

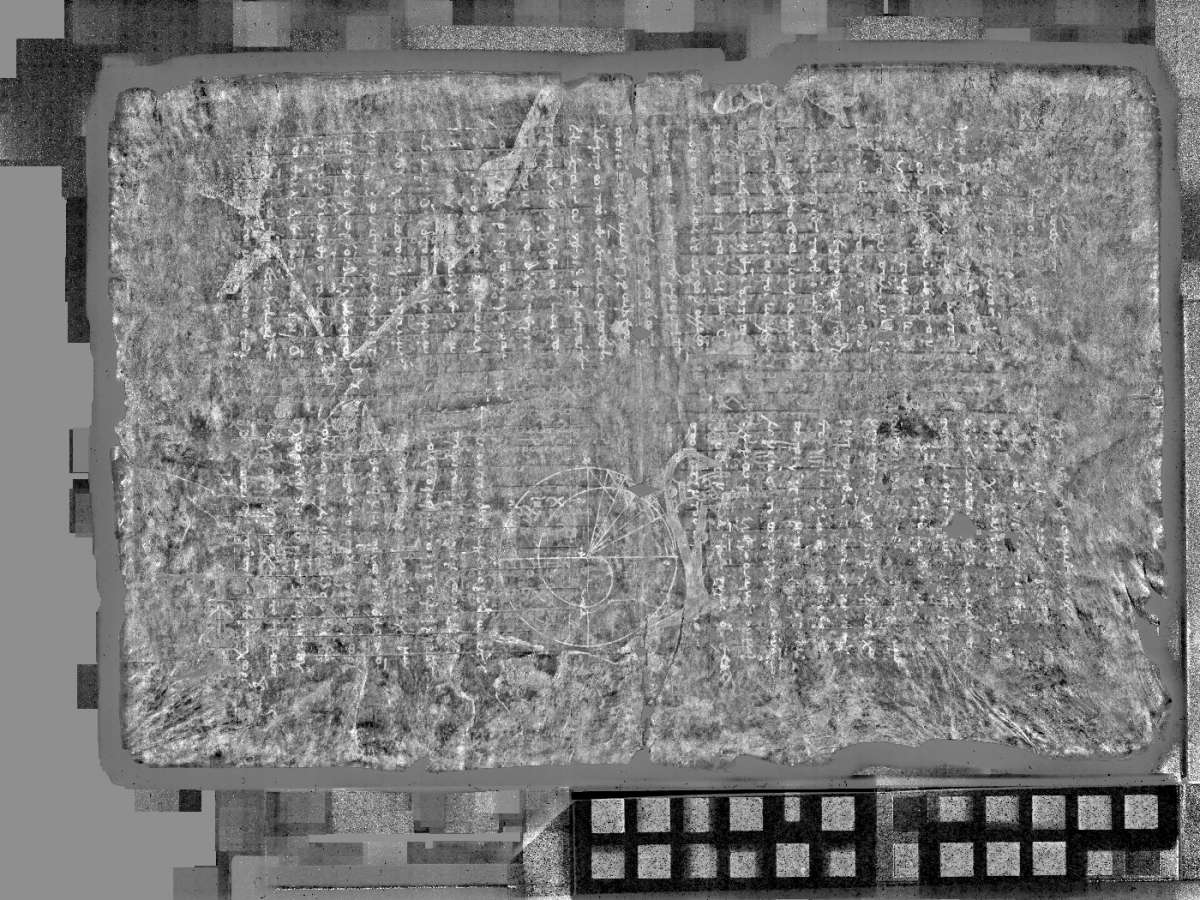

We travel to 1906 when he found himself again in Constantinople. Research on the document was stalled for years by World War I, but in 1998 a team of more than 80 scientists and experts in classical culture, mostly from Stanford University, strove to carry out archaeological work on this and other documents. The X-ray finding they made was, logically, totally unexpected and shocking.