An archaeological excavation in Majoonsuo, Outokumpu, eastern Finland, yielded an astonishing find: a Stone Age child interred with feathers and fur.

On a gravel road in a forest, the archaeological team found the first samples of fur and feathers in a Finnish Mesolithic burial. Funerary practices of thousands of years ago in this region are poorly understood. This is significantly new information to the historians.

Unique find from the Stone Age

It’s hard to piece together ancient civilizations from the few clues that survive today in archaeology. Thousands of other clues are missing, and among them are organic material. Even more so in Finland, where soil acidity rapidly degrades organic material.

However, new research led by the University of Helsinki, Tuija Kirkinen, found that the detectable remains of delicate organic objects in graves can remain in the ground for thousands of years.

The Finnish Heritage Agency was the first to examine the burial in 2018 because it was believed to be in danger of destruction. The site is under a gravel road in a forest, with the top of the tomb partially exposed.

The deposit was found due to the intense red color of the ocher. This iron-rich clay soil was also used in cave art around the world.

During the excavation only a few teeth were found, determining that it was a boy between 3 and 10 years old. Transverse quartz arrowheads and two other possible objects of the same material were also found.

According to the shape of the arrowheads and the dating at the level of the coast, it can be estimated that the burial comes from the Mesolithic period of the Stone Age.

Similarly, 24 microscopic fragments of bird feathers were detected, most of them from the down of an aquatic bird. These are the oldest feather fragments in Finland. Although their origin cannot be confirmed with certainty, they may come from clothing, such as a parka or anorak. It is also possible that the child was in a down bed.

Also, a single falcon feather beard was recovered, which probably came from the stringing of quartz arrowheads. It is also possible that falcon feathers were used to decorate the deceased child’s grave or clothing.

Detection processes

Apart from the feathers, 24 fragments of mammalian hair were also found, between 0.5 and 9.5 millimeters in length. Most of them were badly degraded, making identification impossible.

The best finds were the 3 canine hairs, possibly a predator, that were at the bottom of the grave. Although they could also belong to footwear, clothing, or a pet buried next to the child.

The main objective was to investigate how highly degraded plant and animal remains could be traced using soil analysis. For this investigation, 65 bags with soil samples were collected and the university experts separated the organic matter from the samples using water.

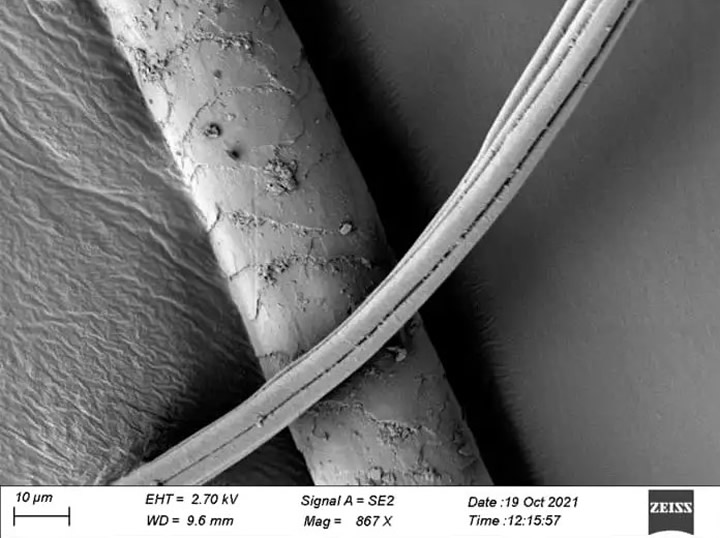

Exposed fibers and hairs were scanned and identified using transmitted light and electron microscopy. A unique fiber separation technique that was developed through research was also used, which it is hoped will provide a model for future studies.

Up to 3 different laboratories examined the remains found, looking for microparticles and fatty acids. The red soil was sieved and gently separated from the parent soil.

Plant fibers also had bast fibers, coming from a willow or nettle. They were probably part of a larger net, perhaps used for fishing or as a cord to tie clothing. Curiously, this is the second find of bast fiber in Finland from the Stone Age.

For the researchers, “all of this gives us valuable insight into Stone Age burial habits, indicating how people had prepared the child for the journey after death.”

It is a eye-opening revelation about how little we know about ancient humanity in certain regions, as well as a reminder that we still have a long way to go to unravel the mysteries of the past.

The research has been published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE. References: Science Alert/ Live Science / IFL Science