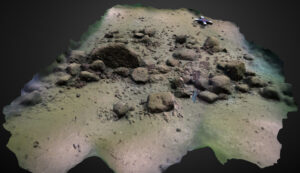

Inhabitants of Siberia have stumbled upon a remarkable prehistoric time capsule in what paleontologists consider the largest hyena lair ever found in Asia. The cave was untouched for 42,000 years and held a variety of animal bones.

Fossils of various creatures, both hunters and hunted, were discovered by paleontologists from the Pleistocene period (spanning from 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). These include brown bears, foxes, wolves, mammoths, rhinos, yaks, deer, gazelles, bison, horses, rodents, birds, fish, and frogs.

On June 20, the scientists released a video clip (in Russian) of their discovery.

Residents of Khakassia, a republic in southern Siberia, discovered the cave five years ago, according to a translated statement from the V. S. Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy. However, due to the remoteness of the area, paleontologists weren’t able to fully explore and examine the remains until June 2022.

Paleontologists gathered approximately 880 pounds (400 kilograms) of bones, including two full cave hyena skulls. It is hypothesized that the hyenas resided in the cave due to the gnaw marks on the bones matching hyena teeth.

“Rhinos, elephants, deer with characteristic bite marks. In addition, we came across a series of bones in anatomical order. For example, in rhinos, the ulna and radius bones are together,” Dmitry Gimranov, senior researcher at the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said in the statement. “This suggests that the hyenas dragged parts of the carcasses into the lair.”

The researchers also found the bones of hyena pups – which tend not to be preserved as they are so fragile – indicating they were raised in the cave. “We even found a whole skull of a young hyena, many lower jaws, and milk teeth,” Gimranov said.

The region of Siberia is teeming with ancient animal remains, which are generally too recent to have been fossilized. The remains of these animals, including bones, skin, flesh, and even blood, often remain remarkably well-preserved, nearly unchanged from the time of their death. This is primarily due to the cold weather effectively preserving them.

Sent to Yekaterinburg for closer examination, the bones could reveal to researchers information about the flora and fauna of that time, what animals ate, and what the climate was like in this area. Dmitry Malikov, senior researcher from the Institute of Geology and Mineralogy of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said in the statement.

“We will also get important information from the coprolites,” the fossilized feces of the animals, he added.