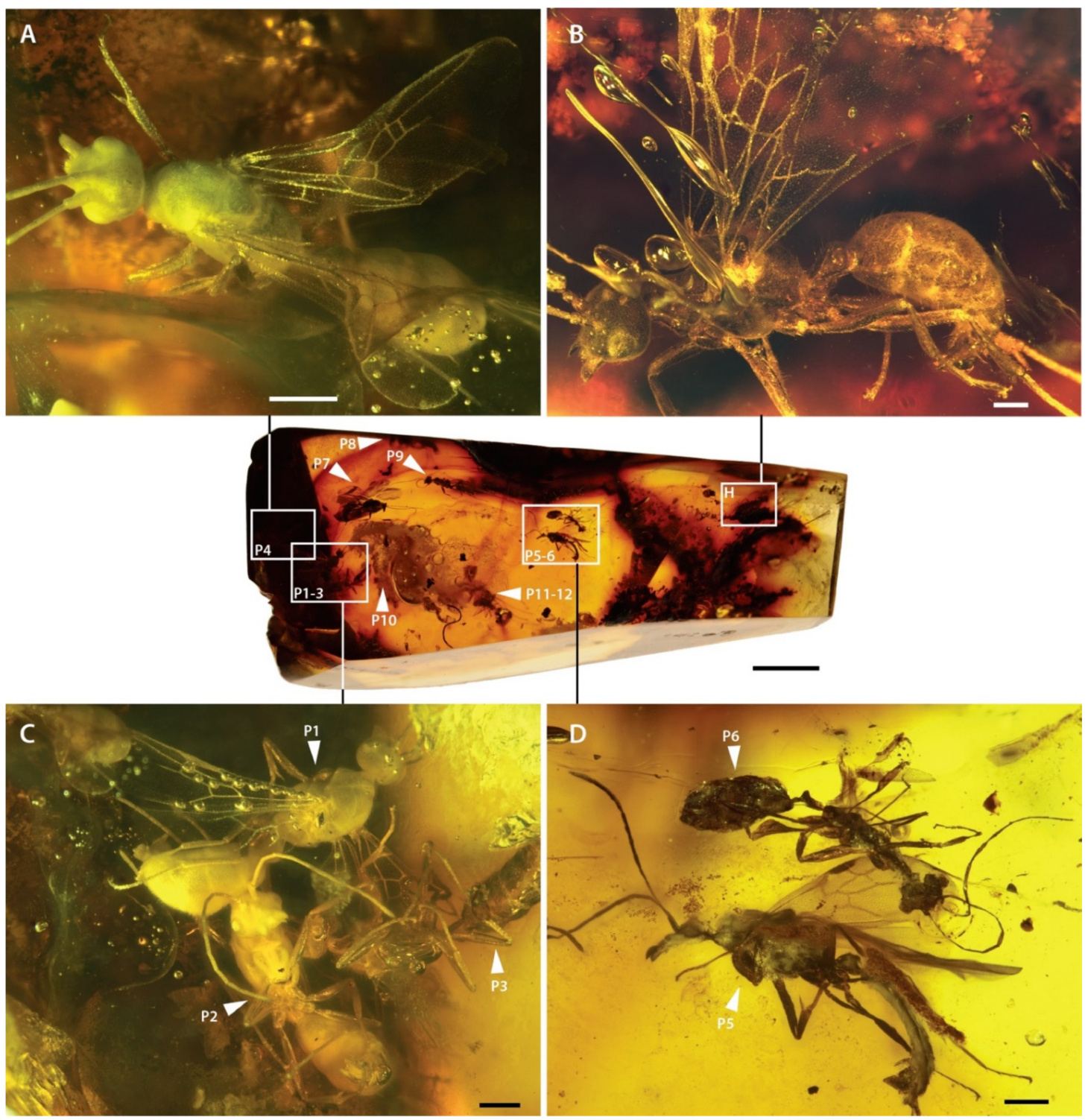

An international team of scientists has discovered a previously unknown extinct ant species encased in a unique piece of amber from Africa. Using the X-ray light source PETRA III at the German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg the researchers, from Friedrich Schiller University Jena, the University of Rennes in France, the University of Gdansk in Poland, as well as the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon in Geesthacht, Germany, had examined the critical fossil remains from 13 individual animals in the amber and realized that they could not be attributed to any previously known species.

The name given to the new species and genus is “†Desyopone hereon gen. et sp. nov.” In this way, the scientists are honoring the two research institutions involved—DESY and Hereon—which contributed significantly to this find with the help of modern imaging techniques. Ultimately, it was only possible to identify the new species and genus through the combination of extensive phenotype data from scans and recent findings from genome analyses of living ants. The team reports on its discovery in the research journal Insects.

Ponerinae instead of Aneuretinae

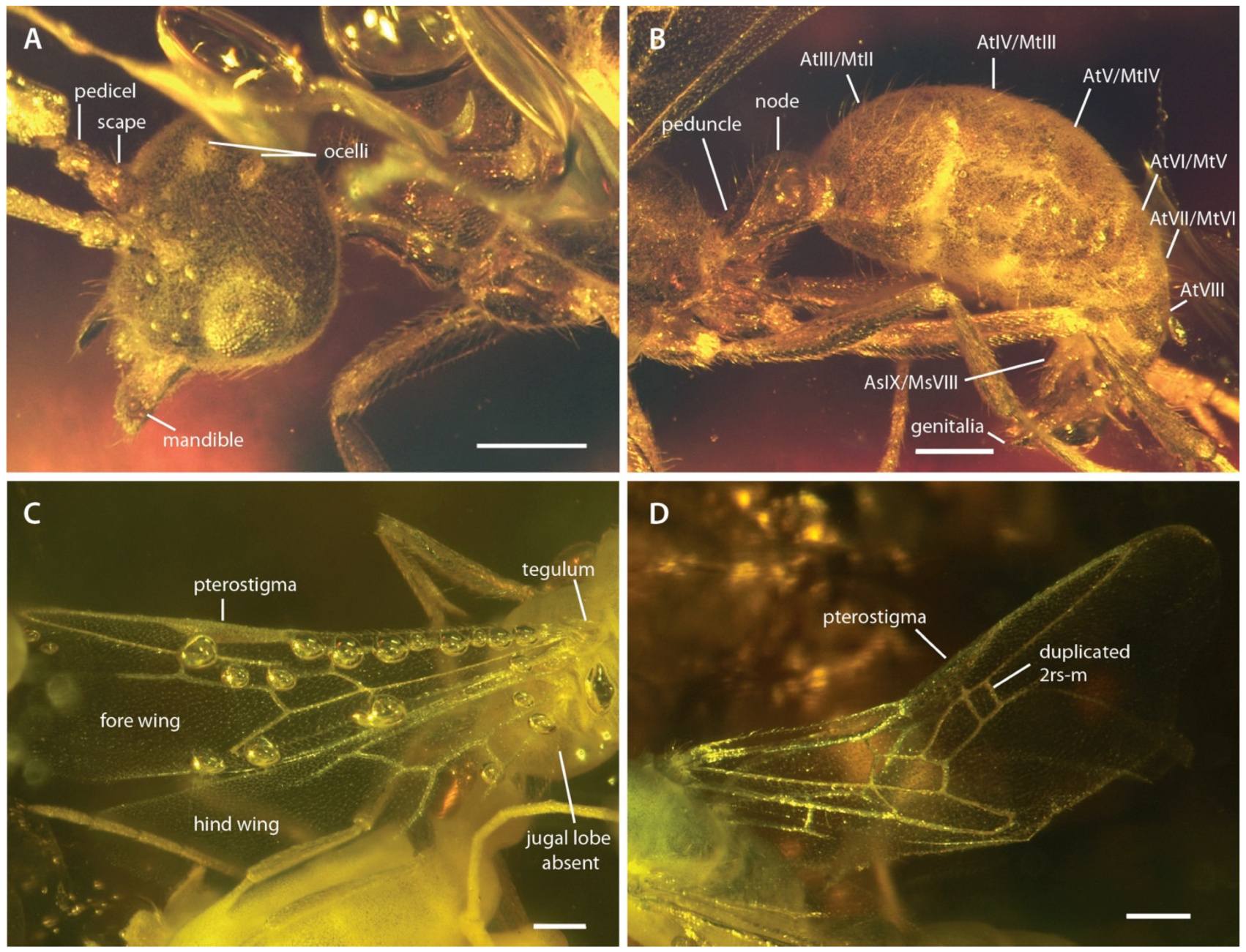

Initial anatomical comparisons led the scientists to hypothesize that the animals were a species of Aneuretinae, an almost extinct subfamily of ants known so far only through fossils and through a single living species from Sri Lanka. But they revised this identification thanks to the high-resolution images obtained by synchrotron micro-computed tomography.

“The complex waist segment and the large but rudimentary mandibles—the mouthparts—are more familiar to us from the Ponerinae, a dominant group of predatory ants,” says Brendon Boudinot, who is currently working at the University of Jena on a Humboldt Research Fellowship. “For this reason, we’ve assigned the new species and genus to this subfamily, even though it has a unique appearance, as the long waist and otherwise unconstricted abdomen are more reminiscent of the Aneuretinae.”

The present research results also contribute to putting male ants more under the spotlight of evolutionary research. “Because they have such a different body shape compared to the worker ants, all of whom are female, research has neglected them for a long time. This is because males are simply too often overlooked because they cannot be properly classified,” says ant expert Boudinot. “Our results not only update the literature on identifying male ants, but also show that by understanding male-specific features, such as the sex-specific shape of the mandible, we can learn more about the evolutionary patterns of female ants.”

This is because in the present study, the researchers have identified a fundamental pattern that occurs in all ants, namely that male and female mandibles follow the same developmental pattern in most species, even if they look very different.

Unique amber

Dating the find also presented the scientists with some challenges, as the amber itself is as unique as the organisms inside it. “The piece with these ants is from the only amber deposit in Africa so far that has featured fossil organisms in inclusions. Altogether, there are only a few fossil insects from this continent. Although amber has long been used as jewelry by locals in the region, its scientific significance has only become clear to researchers in the last 10 years or so,” explains Vincent Perrichot from the University of Rennes.

“The specimen therefore offers what is currently a unique insight into an ancient forest ecosystem in Africa.” It dates from the early Miocene and is 16 to 23 million years old, says Perrichot. Its complicated dating was only possible indirectly, by determining the age of the fossil palynomorphs—the spores and pollen—enclosed in the amber.

Modern methods for looking into the distant past

Research results such as these are only possible through the use of state-of-the-art technology. As the genetic material of fossils cannot be analyzed, precise data and observations on the morphology of animals are particularly important. Comprehensive data can be obtained using high-resolution imaging techniques, such as micro-computed tomography (CT), in which X-rays are used to look through all layers of the sample.

“Since the ants enclosed in amber that are to be examined are very small and only show a very weak contrast in classical CT, we carried out the CT at our measuring station, which specializes in such micro-tomography,” explains Jörg Hammel from the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon. “This provided the researchers with a stack of images that basically showed the sample that was being studied slice by slice.”

Put together, these produced detailed three-dimensional images of the internal structure of the animals, which the researchers could use to reconstruct the anatomy with precision. This was the only way to exactly identify the details that ultimately led to the new species and genus being determined.

The study originally published on MDPI (Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute). September 01, 2022.