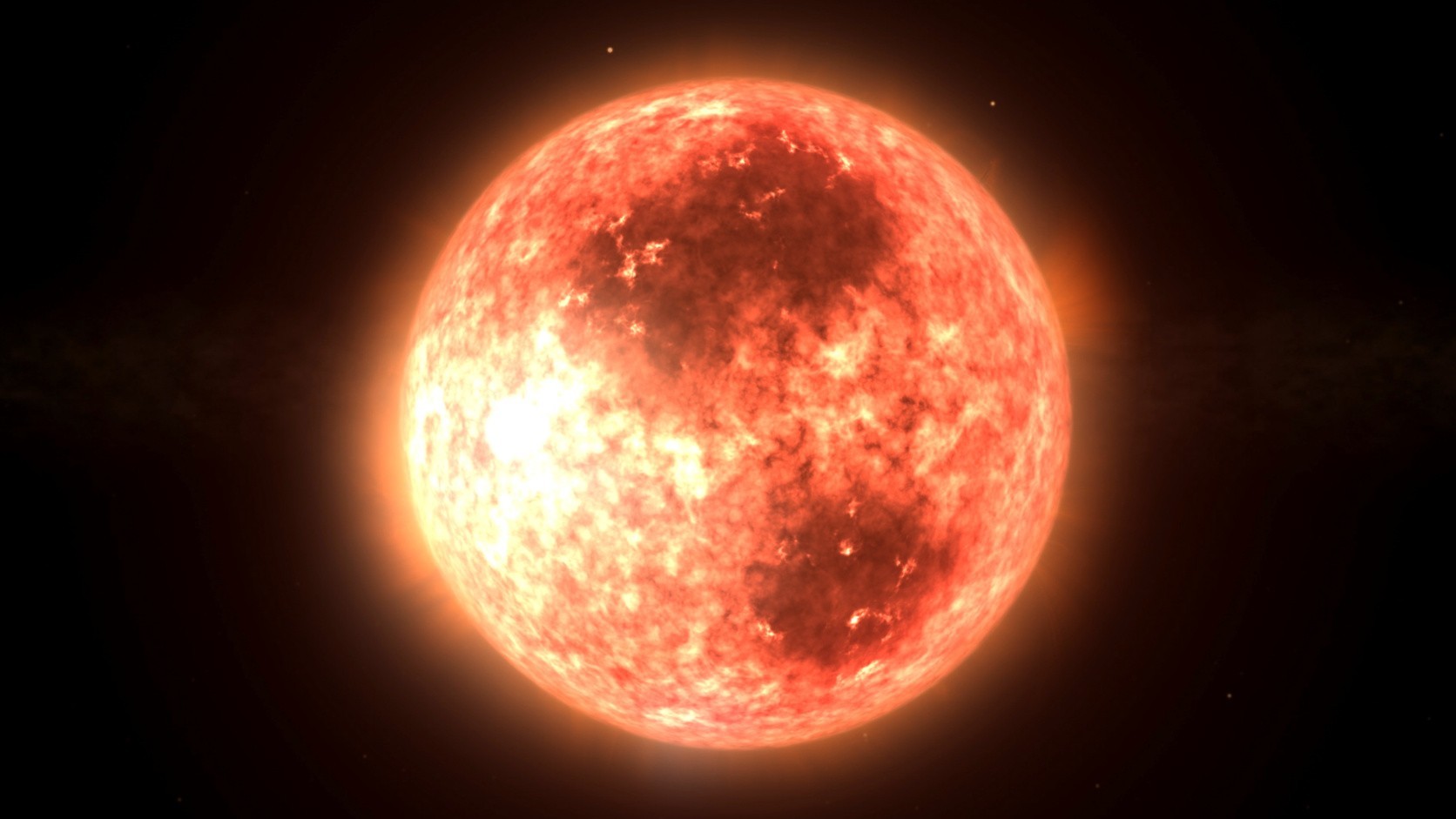

Red dwarfs are the most common stars in our galaxy. Smaller and cooler than the Sun, their high number means that many of the Earth-like planets found so far by scientists are in orbit of one of them. The problem is that, to maintain temperatures that allow the existence of liquid water, an essential condition for life, these planets have to orbit very close to their stars, much more, in fact, than the Earth does to the Sun.

The downside is that red dwarfs are capable of generating intense flares, much more violent and energetic than those launched by our relatively peaceful Sun, and that has made scientists doubt their ability to host planets capable of sustaining life.

How do flares affect?

It is no secret that, to a large extent, life on Earth depends on the energy of its star in order to exist. Which does not mean that sometimes, as all stars do, the Sun brings out its genius and sends us strong flares that have the potential to render our power plants and telecommunications networks useless. Despite this, the Sun is relatively weak compared to other stars. And among the most violent are, precisely, the red dwarfs.

Now, a team of researchers has studied how the activity of these flares can affect atmospheres and the capacity to support life of planets similar to ours that orbit around low-mass stars. They presented their findings Wednesday at the 235th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Honolulu. The work has just been published in Nature Astronomy.

In the words of Allison Youngblood, an astronomer at the University of Colorado at Boulder and a co-author of the study, “Our Sun is a quiet giant. It is older and not as active as the smaller, younger stars. In addition, the Earth has a powerful magnetic shield that deflects most of the damaging winds from the Sun. The result is a planet, ours, teeming with life.”

But for planets that orbit red dwarfs, the situation is very different. In fact, we know that the solar flares and associated coronal mass ejections emitted by these stars can be very detrimental to the prospects for life on these worlds, many of which also do not have magnetic shields. Indeed, according to the authors, these events have a profound influence on the habitability of planets.

Eventual flares and splashed over time (as happens with the Sun) are not a problem. But in many red dwarfs, this activity is practically continuous, with frequent and prolonged flares. In the study, says Howard Chen of Northwestern University and the first author of the paper, “we compared the atmospheric chemistry of planets that experience frequent flares with planets that do not experience flares. Long-term atmospheric chemistry is very different. The continuous flares, in effect, push the atmospheric composition of a planet to a new chemical equilibrium.”

A hope for life

The ozone layer in the atmosphere, which protects a planet from harmful ultraviolet radiation, can be destroyed by intense flare activity. However, during their study the researchers were surprised: in some cases, ozone did indeed persist despite the flares.

In the words of Daniel Horton, lead author of the research, “We have discovered that stellar eruptions may not exclude the existence of life. In some cases, burning does not erode all atmospheric ozone. Life on the surface might still have a chance to fight.”

Another positive side of the study is the discovery that the analysis of solar flares can help in the search for life. In fact, flares can make it easier to detect some gases that are biomarkers. The researchers found, for example, that a stellar flare can highlight the presence of gases such as nitric acid, nitrous dioxide and nitrous oxide, which can be generated by biological processes and therefore indicate the presence of life.

“Space weather phenomena,” says Chen, “are often seen as a liability to habitability. But our study quantitatively showed that these phenomena can help us detect important gas signatures that could signify biological processes.”