The discovery of two perfectly preserved cave lion cubs in Siberian permafrost has given scientists an incredible insight into how this extinct species lived and thrived in harsh northern environments.

The cubs have lain untouched for tens of thousands of years, providing a treasure trove of information for researchers about these magnificent creatures.

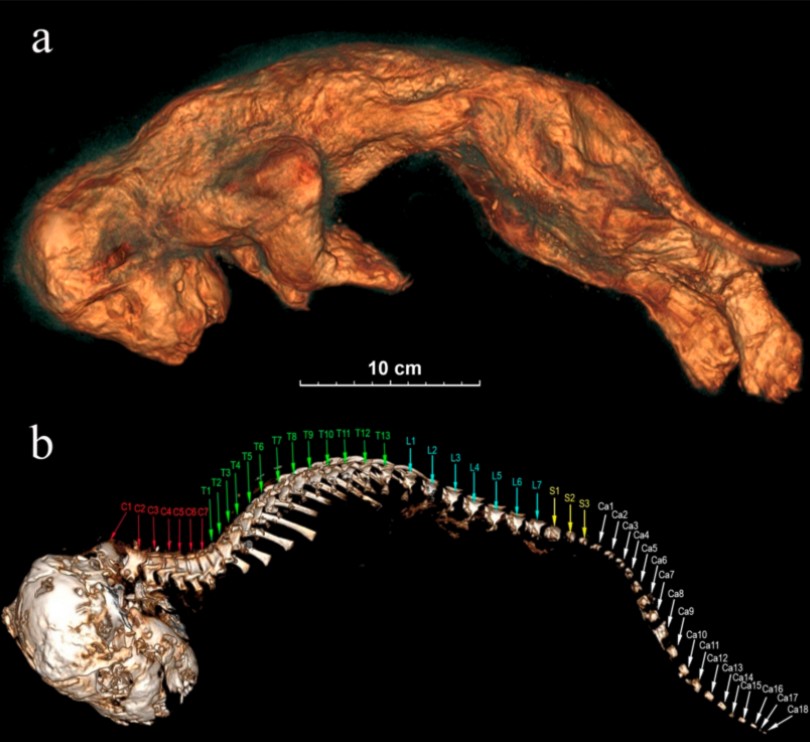

A team led by Russian researchers Gennady Boeskorov and Alexey Tikhonov from the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Centre for Paleogenetics in Sweden recently examined the mummified bodies of two cave lion cubs nicknamed “Sparta” and “Boris” who were discovered on the banks of the Semyuelyakh River in Siberia a few years ago. Their findings have been published in the journal Quaternary in Aug. 2021.

A study on the pair was published in August 2020, demonstrating that extinct cave lions (Panthera spelaea) were a distinct species from modern-day lions (Panthera leo) found in Sub-Saharan Africa. According to genetic evidence, the two families split up roughly 1.9 million years ago.

The crew has returned with a new examination of the anatomy of the cubs. Scientists have previously utilized animal portrayals in cave art, as well as comparisons with African lions, to determine the appearance of cave lions – but these two cubs provide an unprecedented glimpse at this extinct species.

Sparta, previously Spartak, is said to be the best-preserved Ice Age creature yet discovered. Her golden fur is nearly undamaged, albeit slightly matted, and her teeth, skin, soft tissue, and organs are all wonderfully preserved. According to the study, a cave lion cub’s coat hair is identical to that of an African lion cub, with cave lions characterized by long, thick fur undercoats that helped them survive the freezing temperature.

Because they were discovered so close together, the two were supposed to be siblings, but radiocarbon dating indicated Sparta is 27,962 years old and Boris is 43,448 years old.

According to the latest study, both cubs died when they were 1-2 months old. There was no evidence of predators or scavengers causing damage to their remains, yet they discovered shattered skulls, broken ribs, and bodies deformed into odd shapes. They believe the pair died in two distinct mudslides millennia apart based on this odd post-mortem.

The cave lion was widespread in eastern Siberia during the Late Pleistocene period, but evidence of the species has been discovered over most of Eurasia and even North America in what is now known as Alaska.

Cave lions, like many other great mammals of the Pleistocene epoch, went extinct around 14,000 years ago during the final major extinction event at the end of the last Ice Age. Fortunately, the Siberian permafrost’s sub-zero temperatures permitted these specimens to survive in unusually fine shape, providing insights into how they once lived.

The study was originally published in Aug. 2021, in the journal Quaternary.