On the Varna necropolis, a cemetery dating back to 4,460 – 4,450 BC. on the Bulgarian Black Sea coast, archaeologists have discovered the earliest gold artifacts ever discovered.

The Varna Cemetery, also known as the necropolis of Varna, is a significant burial ground located in the city’s western industrial zone and is widely regarded as one of the world’s most significant prehistoric archaeological sites. It dates back to the chalcolithic (copper) era of the Varna culture, which began around 6,000–6,500 years ago.

According to the Archeology of Bulgaria, a total of 294 tombs have been unearthed in the necropolis of Varna. Many of them contain sophisticated examples of metallurgy (gold and copper), pottery (about 600 pieces, including gold-painted ones), high-quality flint and obsidian blades, beads, and shells.

Tomb 43 is the one tomb that stands out among the rest, despite the fact that many other elite tombs have been uncovered. The skeletal remains of a tall guy who appeared to have been a monarch or leader have been uncovered by archaeologists.

During the construction of a tin factory on the site in 1972, a 22-years-old excavator operator named Raycho Marinov dug up several artifacts and collected them in a shoe box before bringing them to his house. This was how the golden Treasure in Varna was unexpectedly discovered. A few days later, he decided to inform some local archaeologists about the discovery.

After that, a total of 294 chalcolithic graves were unearthed from the necropolis throughout the excavation. Based on the results of radiocarbon dating, the graves of the Copper Age, which are where the golden treasures of Varna were discovered, dating back to between 4,560 and 4,450 BC.

All of these enigmatic treasures are the result of an ancient human civilization that flourished in Europe during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods. This civilization emerged in modern-day Bulgaria and the rest of the Balkans, as well as along the lower Danube and the west coast of the Black Sea. This prehistoric civilization is referred to as “old Europe” by some historians.

The findings from the necropolis point to the possibility that the culture of Varna engaged in commerce with far-flung regions of the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, and that rock salt was most likely shipped out of Provadia-Solnitsata (rock salt mine).

Seashells of the Mediterranean mollusk Spondyla were discovered in the graves of the necropolis of Varna and other chalcolithic sites in northern Bulgaria, leading archaeologists to speculate that they may have been employed as a form of currency by this ancient civilization.

Gold found in several of the tombs leads researchers to conclude that the Balkan Peninsula (southeast Europe) has been ruled by a monarchy since the Copper Age. There are almost 3,000 gold artifacts in the Gold Treasure Brewery, of which there are 28 different varieties weighing a total of 6 kilograms (13.23 lb).

Other precious relics found within the graves included copper, high-quality flint tools, jewelry, shells of Mediterranean mollusks, pottery, obsidian blades, and beads.

Grave no. 43, discovered in 1974 in the heart of the Varna necropolis, contained one of the most intriguing inventories. Its reported height is 1.70–1.75 meters (5 feet 6–8 inches). His tomb contained more than 1.5 kg of gold artifacts, leading researchers to conclude that he was a wealthy and influential member of his community, and perhaps a king or monarch.

The male, who was subsequently referred to as the “Varna man,” was laid to rest with a scepter, which is a symbol of great rank or spiritual power, and wore a sheath made of solid gold around his genitalia.

The burial is extremely important not only because of the grave goods but also because it is the first burial of a male elite known to have taken place in Europe. Before this, the most extravagant funerals and graves were reserved for the women and children of the community.

Beyond the priceless items and revelations about social stratification, the graves in the Varna necropolis have revealed important insights into the religious beliefs and intricate funerary procedures of this ancient civilization through the peculiarities of the graves themselves.

The researchers noticed that the male bodies were all laid out on their backs in the graves, while the female bodies were all put in the fetal position. The most shocking finding, however, was that some tombs contained no bones at all, and it was these “symbolic graves” that yielded the greatest amounts of gold and other treasures.

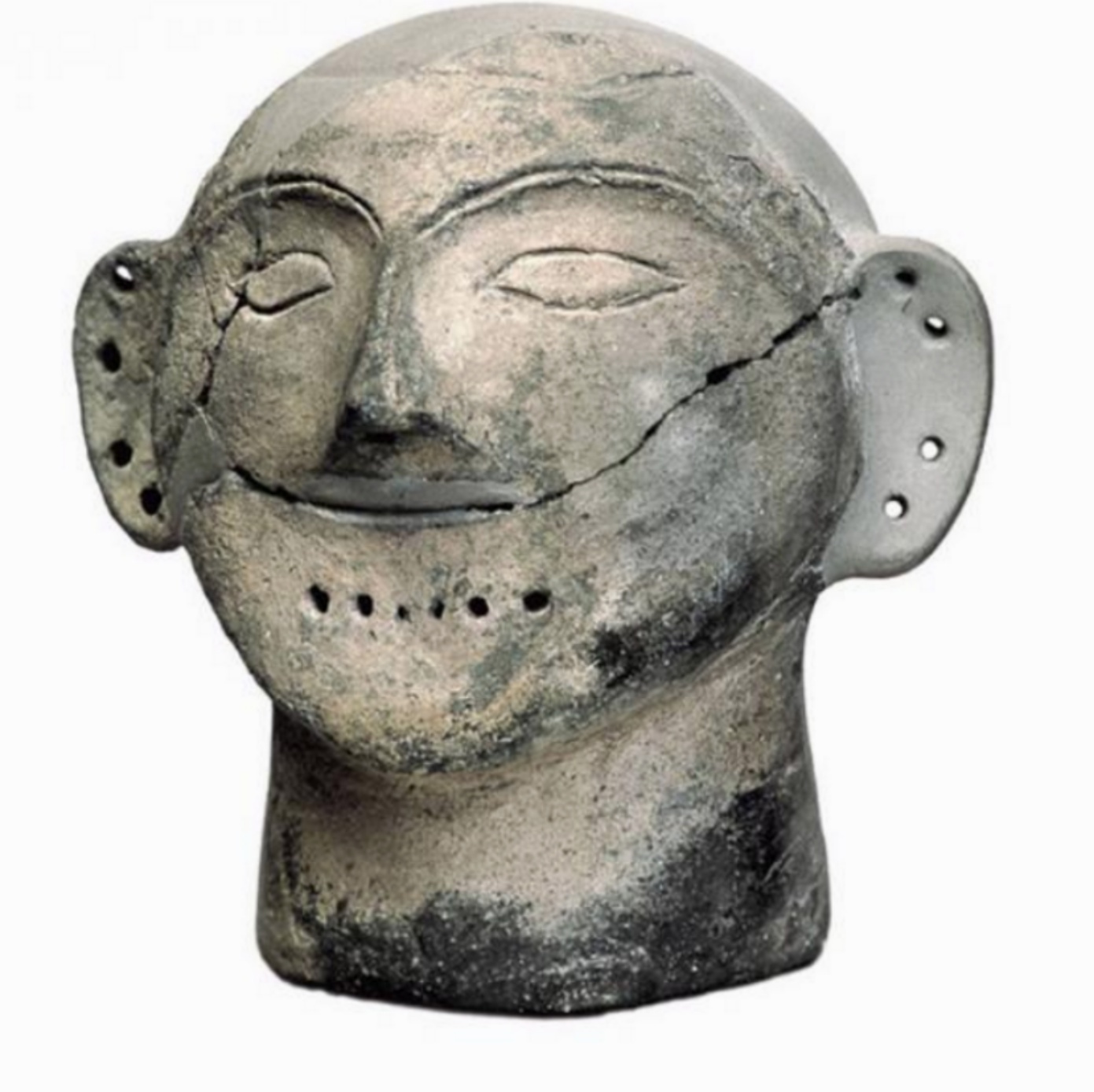

There were also masks of unfired clay, roughly the size of a human, placed in the cenotaphs in certain cases to represent the place of the head.

There are no known living descendants of the Varna civilization, yet this ancient culture left behind many valuable legacies and paved the way for the development of later European civilizations. Their mastery of metalworking was without parallel in Europe or the rest of the globe, and their culture displayed the hallmarks of an exceptionally sophisticated and developed society.