The link between a fossil found in a cave in northern Laos and stone tools made in north Australia is us – Homo sapiens. Our ancestors, when they initially arrived in Southeast Asia while traveling from Africa to Australia, left behind evidence of their existence in the shape of human fossils which had been stored for thousands of years in a cave.

The research team, made up of scientists from Laos, France, the US, and Australia, has uncovered definitive proof, published in journal Nature, from Tam Pà Ling cave in Laos that indicates that modern humans migrated from Africa to Asia sooner than initially believed.

The evidence supports that our forefathers did not simply trace the shorelines and islands. Instead, it appears they journeyed through woodlands, probably by means of river beds. Subsequently, some of them went on to traverse Southeast Asia before eventually becoming the initial inhabitants of Australia.

University of Copenhagen paleoanthropologist Assistant Professor Fabrice Demeter, one of the paper’s lead authors, has indicated that Tam Pà Ling is becoming increasingly important in the narrative of modern human migration across Asia; however, its significance has only recently been appreciated.

The project was supported by three Australian Universities, including Macquarie University and Southern Cross University which employed multiple techniques to date samples. Flinders University revealed that sediment in the cave had been accumulated in distinct layers over a period of tens of thousands of years.

In 2009, a skull and mandible were unearthed from the first excavation of the cave, resulting in a lot of debate. Our passage from Africa to Southeast Asia is generally related to islands like Sumatra, the Philippines, and Borneo.

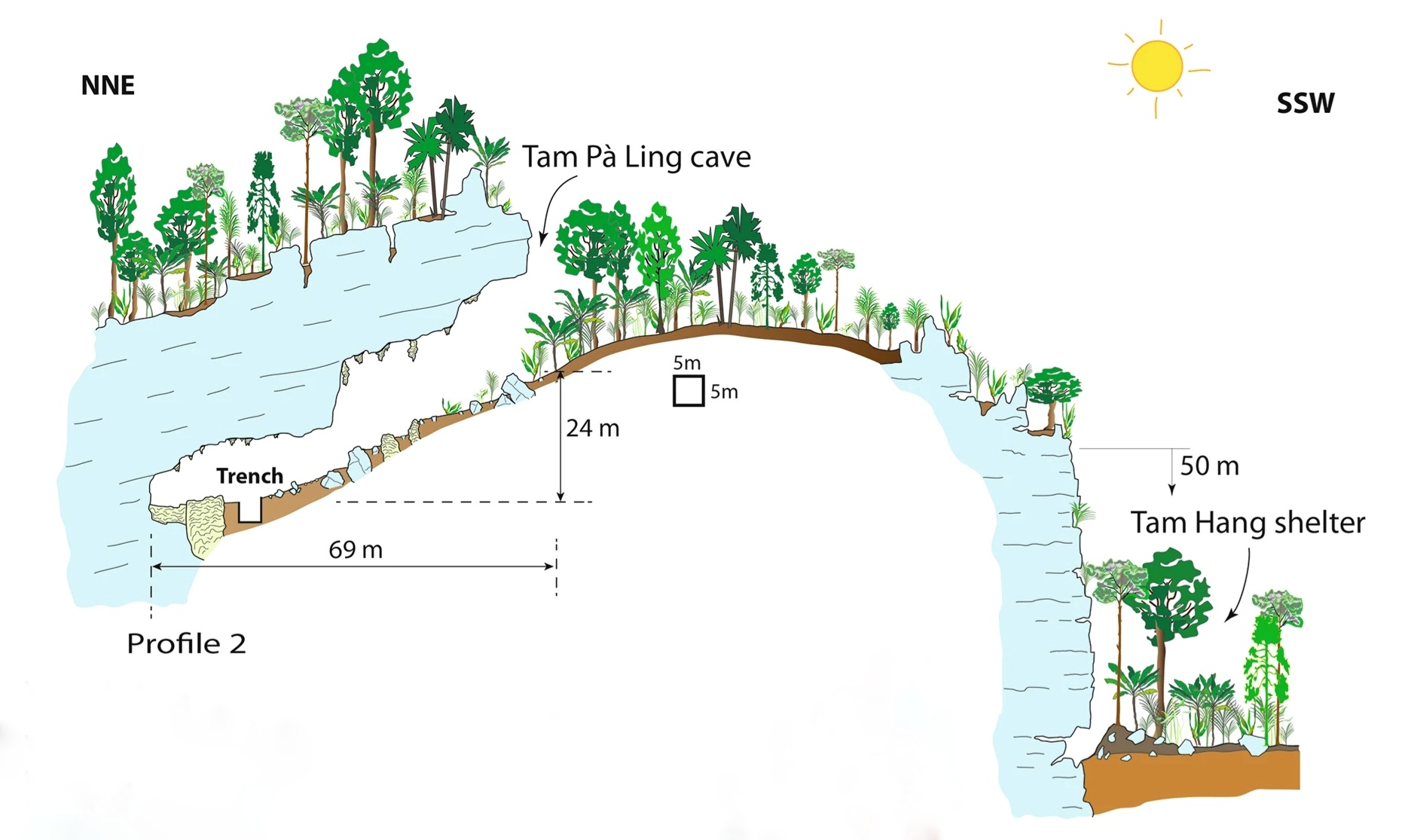

In an upland cave site called Tam Pà Ling, located 300 kilometers away from the sea in northern Laos, a mystery was brought to light. The skull and jawbone were confirmed to be from Homo sapiens who had passed through the area. However, the question of when this occurred remained unanswered.

When it comes to human emigration, the quarrel is often about when it happened. Unfortunately, this proof was difficult to determine the age of.

Due to the protected status of the human fossils in the World Heritage area, and the fact that the site is too ancient for radiocarbon dating, the burden of creating a timeline has fallen to luminescence dating of the sediments. There are very few animal bones or suitable decorations to assist in the dating process.

The process of luminescence dating relies on a light-sensitive signal that returns to its beginning point (zero) when exposed to light, however builds up over time when kept from light during burial. Initially, it was used to restrict the burial sediments that encased the fossils.

The process of luminescence dating involves a light-sensitive signal that returns to its beginning point when confronted with light, however, accumulates over time when kept from light during interment. Initially, it was utilized to restrict the sedimentation that was covering the fossils.

Associate Professor Kira Westaway from Macquarie University explains that, had it not been for luminescence dating, the essential evidence of the site would have had no timeline and would have been disregarded in the supposed path of dispersal throughout the region. Fortunately, the approach is quite flexible and can be adjusted to suit different requirements.

It was determined that the minimum age was 46,000 years, a timeline which corroborates with the time when Homo sapiens came to Southeast Asia. But that wasn’t the only thing that was found.

In the period from 2010 to 2023, excavations (delayed by three years of lockdowns) have yielded an increasing amount of evidence that Homo sapiens had ventured through the area on their way to Australia. As the work progressed, seven pieces of human skeletal material were found at various depths within 4.5 meters of sediment, which suggests that the Homo sapiens had arrived in this region much earlier than previously thought.

This team’s research was able to get around these issues by utilizing the uranium-series dating approach on a stalactite point that was buried in sediment, and combining it with electron-spin-resonance dating on two complete bovid teeth found at a depth of 6.5 meters.

Associate Professor Renaud Joannes-Boyau from Southern Cross University noted that the direct dating of fossil remains validated the age sequence acquired by luminescence, which enabled them to develop a complete and reliable timeline of Homo sapiens present at Tam Pà Ling.

The team employed micromorphology to analyze the sediment in order to back up the dating evidence they had. By taking a closer look at the layers under a microscope, they were able to establish the integrity of the layers and prove that sedimentary deposits had been consistently accumulating over an extended period of time.

The site, which is not a rapid dump of sediments, is instead a regularly and seasonally laid stack of sediments, according to Associate Professor Mike Morley from Flinders University. Morley worked with Ph.D. students Vito Hernandez and Meghan McAllister-Hayward on the project.

An investigation into the timeline of the region revealed that humans had been there for over 56,000 years. Evidence of this was the discovery of a fragment of a leg bone at a depth of seven meters, pointing to a time frame of between 86,000 to 68,000 years ago for modern human arrival in Southeast Asia. This is a significant extension of the arrival time by around 40,000 years. However, as genetics show, these earlier migrations did not have a major influence on our present-day populations.

Associate Professor Westaway declares that this specific paper is the one to settle the Tam Pà Ling evidence. He states that now they have sufficient data to confidently declare when Homo sapiens first appeared in the area, how long they were present, and the potential route they took.

The Tam Pà Ling cave is found in close proximity to the newly discovered Cobra Cave, a place that was frequented by Denisovans 70,000 years ago. Though there had been no proof of early human arrival in Southeast Asia until now, this area could be an ancient pathway taken by our ancestors before Homo sapiens.

Associate Professor Westaway believes that we can gain a great deal of knowledge from exploring the caves and forests of Southeast Asia.

The results of the research were documented in the journal Nature on June 13, 2023.