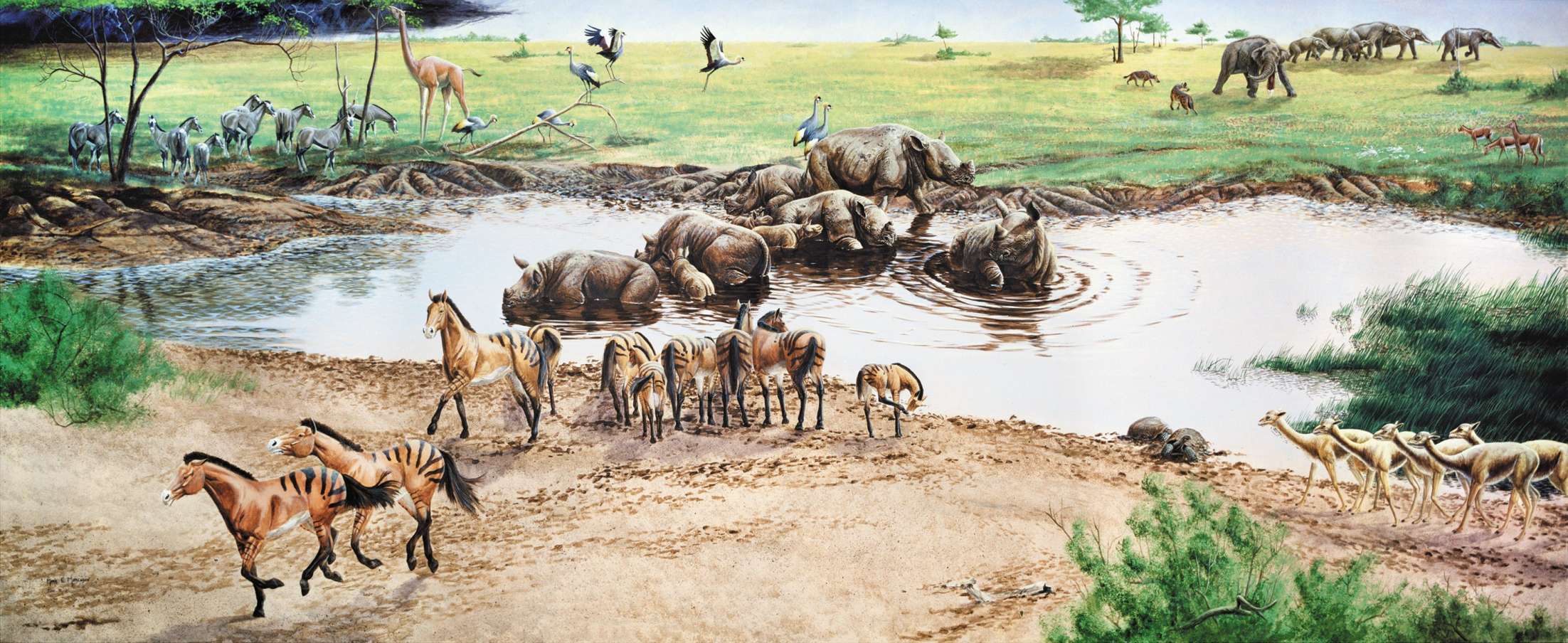

In that distant past, Nebraska was a grassy savanna. Trees and shrubs dotted the landscape. It likely resembled today’s Serengeti National Park in East Africa. The watering holes attracted prehistoric animals among Nebraska’s tall grasslands. From horses to camels and rhinoceroses, with wild dogs looming nearby, animals roamed the savanna-like region.

Then, one day, it all changed. Hundreds of miles away, a volcano in southeast Idaho erupted. Within days, up to two feet of ash covered parts of present-day Nebraska.

Some of the animals died immediately, consumed with ash and other debris. Most of the animals lived for several more days, their lungs ingesting ash as they searched the ground for food. Within a few weeks, northeast Nebraska was barren of animals, except for a few survivors.

More than 12 million years later, in 1971, a fossil was found in Antelope County, near the small town of Royal. The skull of a baby rhino was discovered by a Nebraska paleontologist named Michael Voorhies and his wife while exploring the area. The fossil was exposed by erosion. Soon after, exploration started in the area.

It was found that birds and turtles died quickly as their skeletons lie at the bottom of the ash, right on what was the sandy bottom of the watering hole. Other animals occur in layers.

Above the birds and turtles lie dog-sized saber-tooth deer. Then five species of pony-sized horses, some with three toes. Above those are camel remains. Atop them all are the biggest, the rhinos, in a single layer. All of this is buried under about 2.5 meters (8 feet) of ash. It must have blown into the water, covering the dead.

Fossils in the ash bed are whole. They haven’t been squashed flat. Their bones are all still in place. They’re also fragile. Most fossils form when groundwater soaks into bones and teeth. Over time, minerals from the water fill in the gaps and even replace some of the original bone. The result is a hard, rock-like fossil that can stand the test of time.

Here, however, the ash eventually locked the skeletons away from water. After the watering hole dried up, the super-fine ash left no room between particles for new water to seep in. The ash protected the bones, preserving them in their original positions. But they didn’t mineralize much. When scientists remove the ash around them, these bones start to crumble.

Within few years, as more discoveries were made, the fossil site grew into a tourist attraction. Today, people visit Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park to check out hundreds of fossils from 12 species of animals, including five types of horses, three species of camels, as well as a saber-toothed deer. The infamous saber-toothed cat remains a dream discovery.

Visitors view fossils inside the Hubbard Rhino Barn, a 17,500-square-foot facility that protects the fossils while allowing visitors to roam on a boardwalk. Kiosks provide information on fossils located in specific areas.