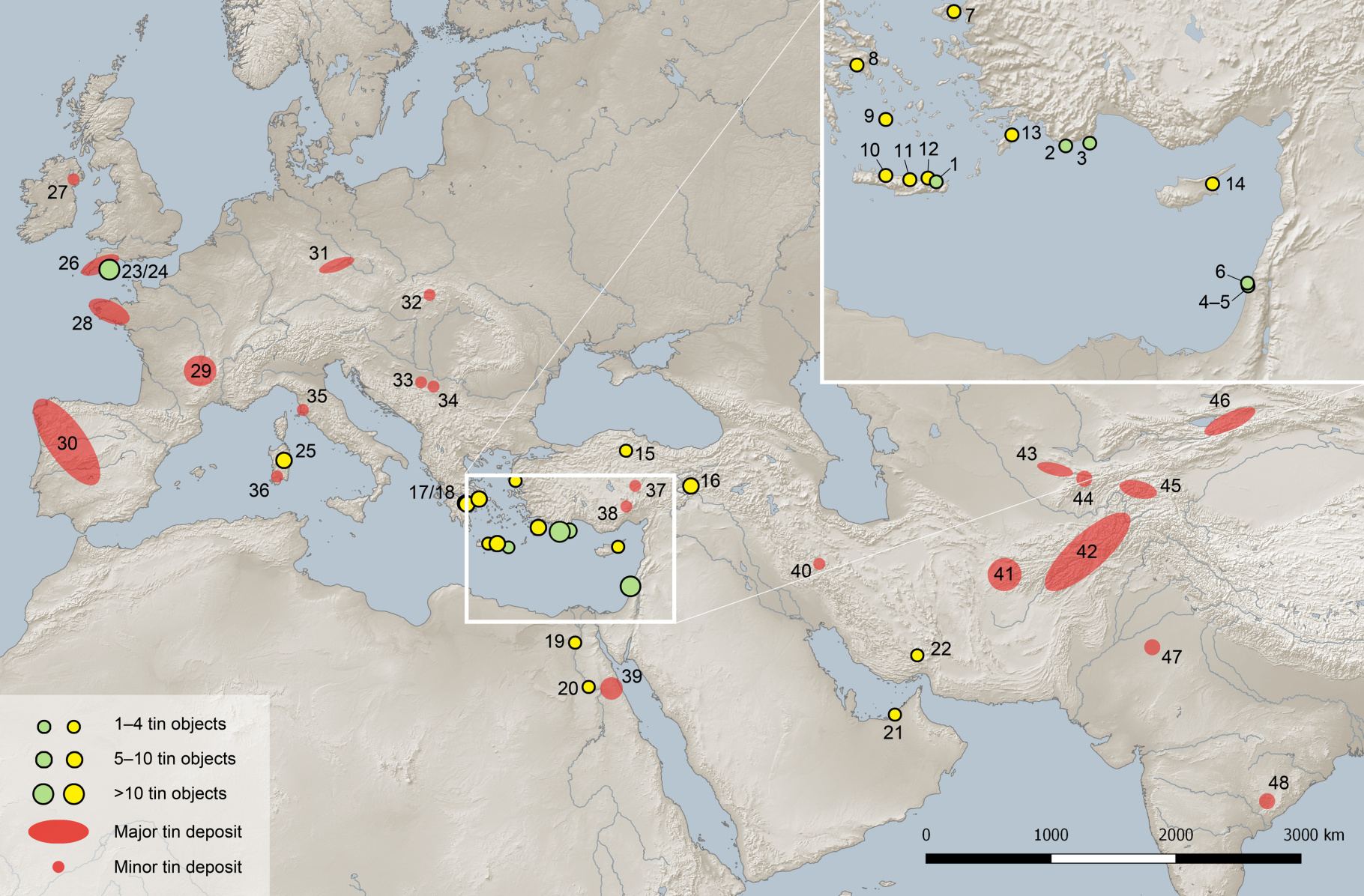

The origin of the tin used in the Bronze Age has long been one of the greatest enigmas in archaeological research. Now researchers have solved part of the mystery. They were able to prove that tin ingots found at archaeological sites in Israel, Turkey, and Greece do not come from Central Asia, as previously assumed, but from tin deposits in Europe.

Using methods of the natural sciences, researchers from Heidelberg University and the Curt Engelhorn Centre for Archaeometry in Mannheim have examined the tin from the second millennium BCE found at archaeological sites in Israel, Turkey, and Greece.

The findings are proof that even in the Bronze Age complex and far-reaching trade routes must have existed between Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean. Highly appreciated raw materials like tin as well as amber, glass, and copper were the driving forces of this early international trade network.

Bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, was already being produced in the Middle East, Anatolia, and the Aegean in the late fourth and third millennia BC. Knowledge on its production spread quickly across wide swaths of the Old World.

“Bronze was used to make weapons, jewelry, and all types of daily objects, justifiably bequeathing its name to an entire epoch. The origin of tin has long been an enigma in archaeological research,” explains Prof. Dr. Ernst Pernicka in a press statement.

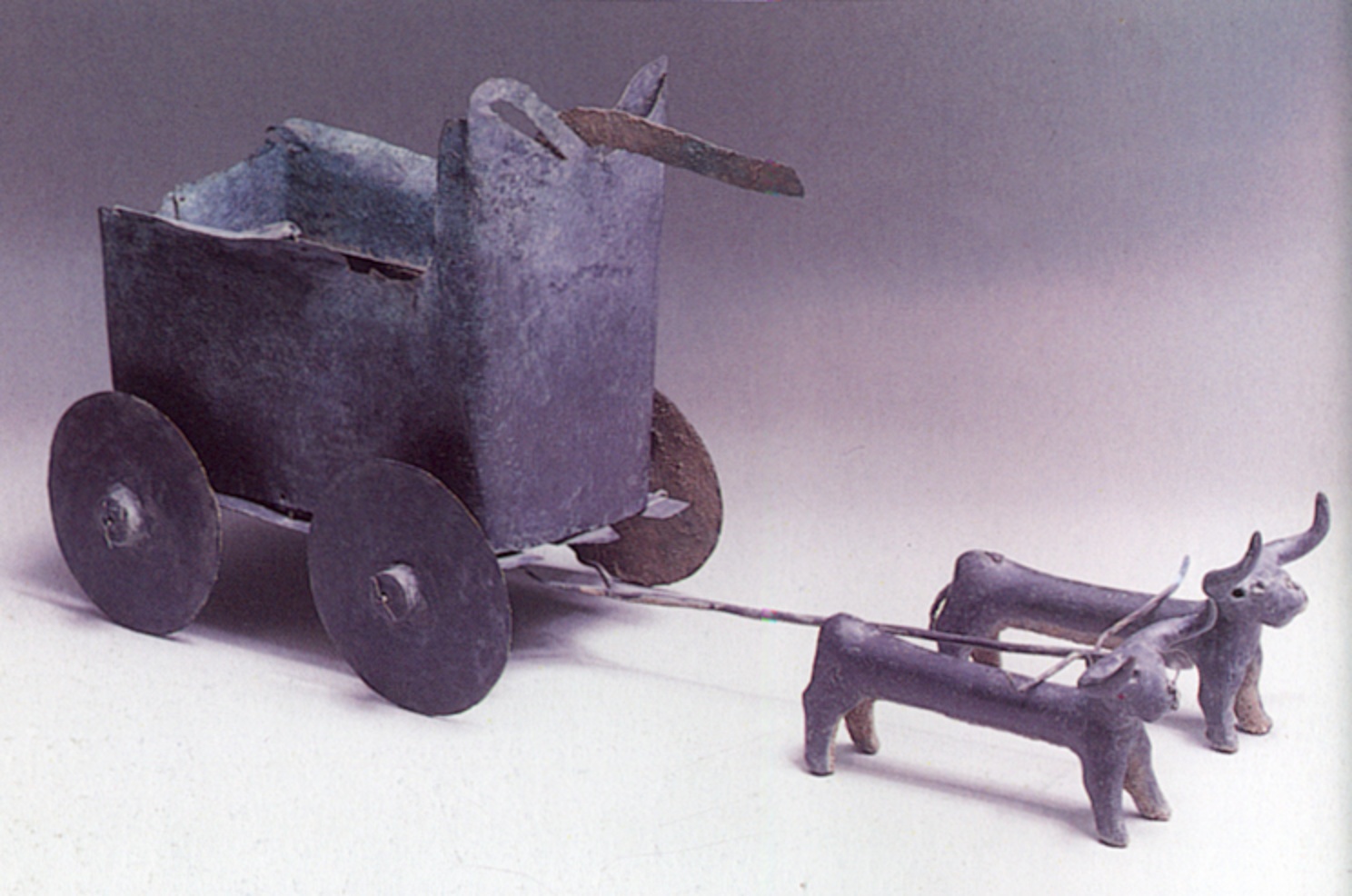

Egypt | Ptolemaic Period, 3rd century BCE |Bronze, wood, ibis bones and skull, remains of a linen textile, and amulets | Gift of Anwar el-Sadat, President of Egypt, to Yigael Yadin © Israel Museum, Jerusalem

“Tin objects and deposits are rare in Europe and Asia. The Eastern Mediterranean region, where some of the objects we studied originated, had practically none of its own deposits. So the raw material in this region must have been imported”, explained the researcher.