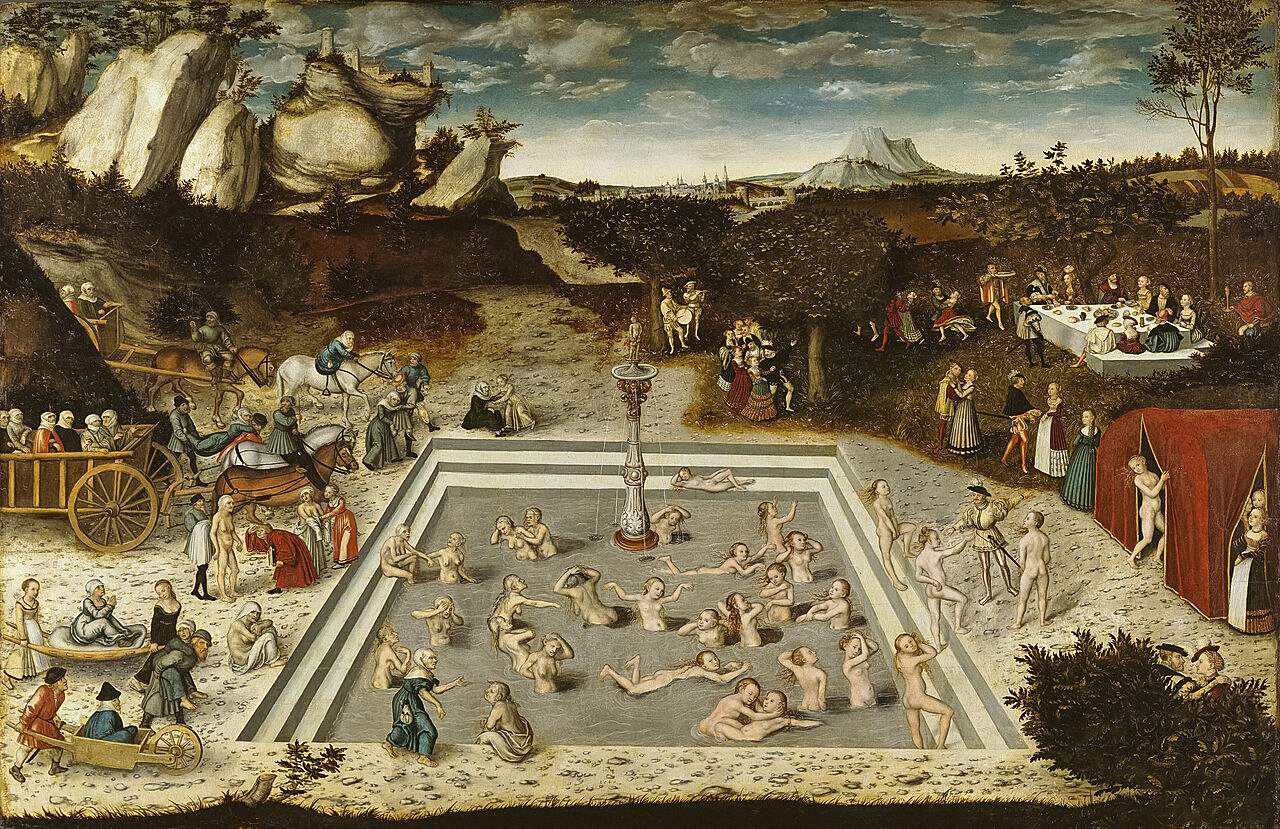

According to popular legend, Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León discovered the present-day state of Florida while searching for the Fountain of Youth. In actuality, stories about magical waters that grant youth or extended life date back to Herodotus or farther.

Alexander the Great, for example, was also said to have come across a healing “river of paradise” in the fourth century BC, and similar legends cropped up in such disparate locations as the Canary Islands, Japan, Polynesia and England. During the Middle Ages, some Europeans even believed in the mythical king Prester John, whose kingdom allegedly contained a fountain of youth and a river of gold.

Although Ponce de León did explore Florida in 1515, the story about the Fountain of Youth did not become attached to his journeys until after his death. In this article, we’ll explore how the Fountain of Youth became associated with his existence. Moreover, we’ll delve into whether he truly uncovered it.

Spanish sources asserted that the Taino Indians of the Caribbean spoke of a magic fountain and rejuvenating river that existed somewhere north of Cuba. These rumors conceivably reached the ears of Ponce de León, who is thought to have accompanied Christopher Columbus on his second voyage to the New World in 1493.

After helping to brutally crush a Taino rebellion on Hispaniola in 1504, Ponce de León was granted a provincial governorship and hundreds of acres of land, where he used forced Indian labor to raise crops and livestock.

In 1508 he received royal permission to colonize San Juan Bautista (now Puerto Rico). He became the island’s first governor a year later, but was soon pushed out in a power struggle with Christopher Columbus’ son Diego.

Having remained in the good graces of King Ferdinand, Ponce de León received a contract in 1512 to explore and settle an island called Bimini. Nowhere in either this contract or a follow-up contract was the Fountain of Youth mentioned.

By contrast, specific instructions were given for subjugating the Indians and divvying up any gold found. Although he may have claimed to know certain “secrets,” Ponce de León likewise never brought up the fountain in his known correspondence with Ferdinand.

Ponce de León set sail in March 1513 with three ships. According to early historians, he anchored off the eastern coast of Florida on April 2 and came ashore a day later, choosing the name “La Florida” in part because it was the Easter season (Pascua Florida in Spanish).

Ponce de León then journeyed down through the Florida Keys and up the western coast, where he skirmished with Indians, before beginning a roundabout journey back to Puerto Rico. Along the way he purportedly discovered the Gulf Stream, which proved to be the fastest route for sailing back to Europe.

Eight years later, Ponce de León returned to Florida’s southwestern coast in an attempt to establish a colony, but he was mortally wounded by an Indian arrow. Just before leaving, he sent letters to his new king, Charles V, and to the future Pope Adrian VI.

Once again, the explorer made no mention of the Fountain of Youth, focusing instead on his desire to settle the land, spread Christianity and discover whether Florida was an island or peninsula. No log of either voyage has survived, and no archaeological footprint has ever been uncovered.

Nonetheless, historians began linking Ponce de León with the Fountain of Youth not long after his death. In 1535 Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés accused Ponce de León of seeking the fountain in order to cure his sexual impotence.

Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, who lived with Indians in Florida for many years after surviving a shipwreck, also derided Ponce de León in his 1575 memoir, saying it was a cause for merriment that he sought out the Fountain of Youth. One of the next authors to weigh in was Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, the Spanish king’s chief historian of the Indies. In 1601 he penned a detailed and widely read account of Ponce de León’s first voyage.

The Fountain of Youth legend was now alive and well. It did not gain much traction in the United States, however, until the Spanish ceded Florida in 1819. Famous writers of the time such as Washington Irving then began portraying Ponce de León as hapless and vain.

Artists also got in on the act, including Thomas Moran, who painted an oversize canvas of Ponce de León meeting with Indians. By the early 20th century, a statue of the explorer had been placed in the central plaza of Florida’s oldest city, St. Augustine, and a nearby tourist attraction pretended to be the actual Fountain of Youth. But the authenticity of the fountain has never been verified even though tens of thousands of visitors come every year to sample the sulfur-smelling well water.

So, did Ponce de León actually discover this mythical source of eternal vitality on American soil?

Well, the jury is still out on that one! The tale of Ponce de León’s quest remains shrouded in mystique, a tantalizing puzzle that has captivated the imagination of historians, storytellers, and adventurers alike. Even as scientific advancements continue to change our understanding of life and longevity, the Fountain of Youth continues to symbolize our collective yearning for immortality.

Whilst it may still be an unsolved mystery, one thing’s for certain — the story of Ponce de León’s pursuit represents an enduring testament to humanity’s relentless quest for discovery and the unknown.