Hadara, the ostrich boy: A feral child who lived with ostriches in the Sahara desert

A child who has grown up completely isolated from people and society is called the “feral child” or the “wild child.” Because of their lack of outward interaction with others, they have no language skills or knowledge of the outside world.

Feral children may have been severely abused, neglected, or forgotten about before finding themselves alone in the world, which only adds to the challenges of trying to adopt a more normal lifestyle. Kids raised in those conditions typically were left on purpose or ran away to escape.

Hadara – The Ostrich Boy:

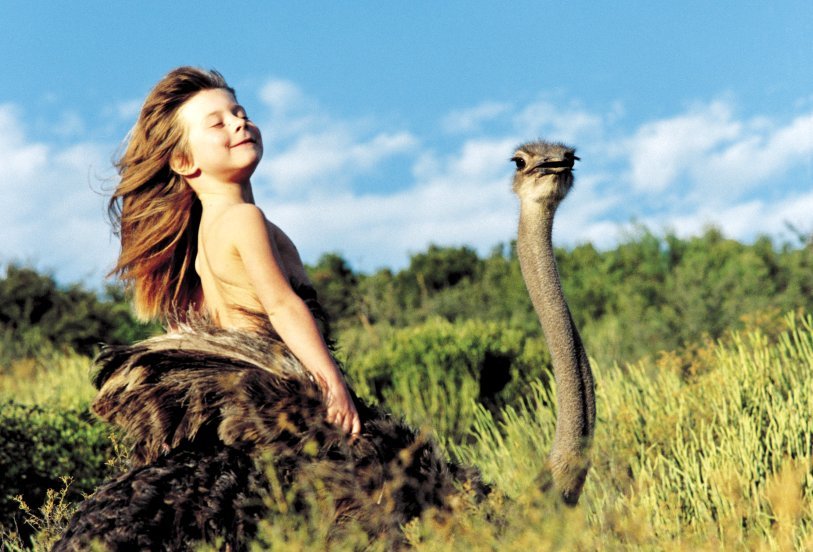

A young boy named Hadara was one such feral child. He was separated from his parents in the Sahara desert at the age of two. His chances for survival were nothing. But fortunately, a group of ostriches took him in and served as a makeshift family. Fully ten years passed before Hadara was finally rescued at the age of twelve.

In 2000, Hadara’s son, Ahmedu, recounted the story of Hadara’s younger days. The story was passed on to Monica Zak, a Swedish author, who wrote a book about this case.

Monica had heard the story of the ‘Ostrich Boy’ from the storytellers when she was travelling through the Sahara desert as a reporter. Having visited the tents of nomad families in the liberated part of Western Sahara and also many families in the huge camps with refugees from Western Sahara in Algeria she had learnt that the proper way of greeting a visitor is with three glasses of tea and a good story.

Here’s How Monica Zak Stumbled Upon The Story Of The ‘Ostrich Boy’:

On two occasions she heard a story about a small boy who was lost in a sandstorm and was adopted by ostriches. He grew up as part of the flock and was the favourite son of the ostrich couple. At the age of 12, he was captured and returned to his human family. The storytellers she heard telling the story of the ‘Ostrich Boy’ finished by saying: “His name was Hadara. This is a true story.”

However, Monica did not believe it was a true story, but it was a good one so she planned to publish it in the magazine Globen as an example of storytelling amongst the Sahrawi in the desert. In the same magazine, she also had several articles about the life of the children in the refugee camps.

When the magazine was published she was invited to the Stockholm office of the representatives of Polisario, the organization of the Sahrawi refugees. They thanked her for writing about their sad plight, about them living in refugee camps in the most inhospitable and hot part of the Algerian desert since 1975 when their country was occupied by Morocco.

However, they said, they were especially grateful that she had written about Hadara. “He is dead now”, one of them said. “Was it his son that told you the story?”

“What?” Monica said flabbergasted. “Is it a true story?”

“Yes”, the two men said with conviction. “Didn’t you see the refugee kids dancing the ostrich dance? When Hadara returned to live with human beings he taught everyone to dance the ostrich dance because ostriches always dance when they are happy.”

Having said that, the two men started dancing Hadara’s ostrich dance, flapping their arms and craning their necks among the tables and computers of their office.

Conclusion:

Although the book, that Monica Zack wrote about the ‘Ostrich Boy’, is based on many real experiences, it is not completely nonfiction. The author added some of her own fantasy to it.

Like us, ostriches walk and run on two legs. But they can reach speeds of up to 70km per hour ― about twice the speed of the fastest human. In the story of the ‘Ostrich Boy’, the only question that remains in the end is: How can a human child adapt to such a group of one of the world’s fastest creatures?