There are over two hundred megalithic structures that have been discovered in the province of Huelva in southwest Spain. One of these structures is particularly impressive while also being mysterious and puzzling.

Dolmen de Soto is a massive underground structure that dates back thousands of years and is buried beneath a mound that is sixty meters in diameter. It is frequently referred to as Spain’s underground Stonehenge and is one of the largest circular megalithic arrangements in Spain.

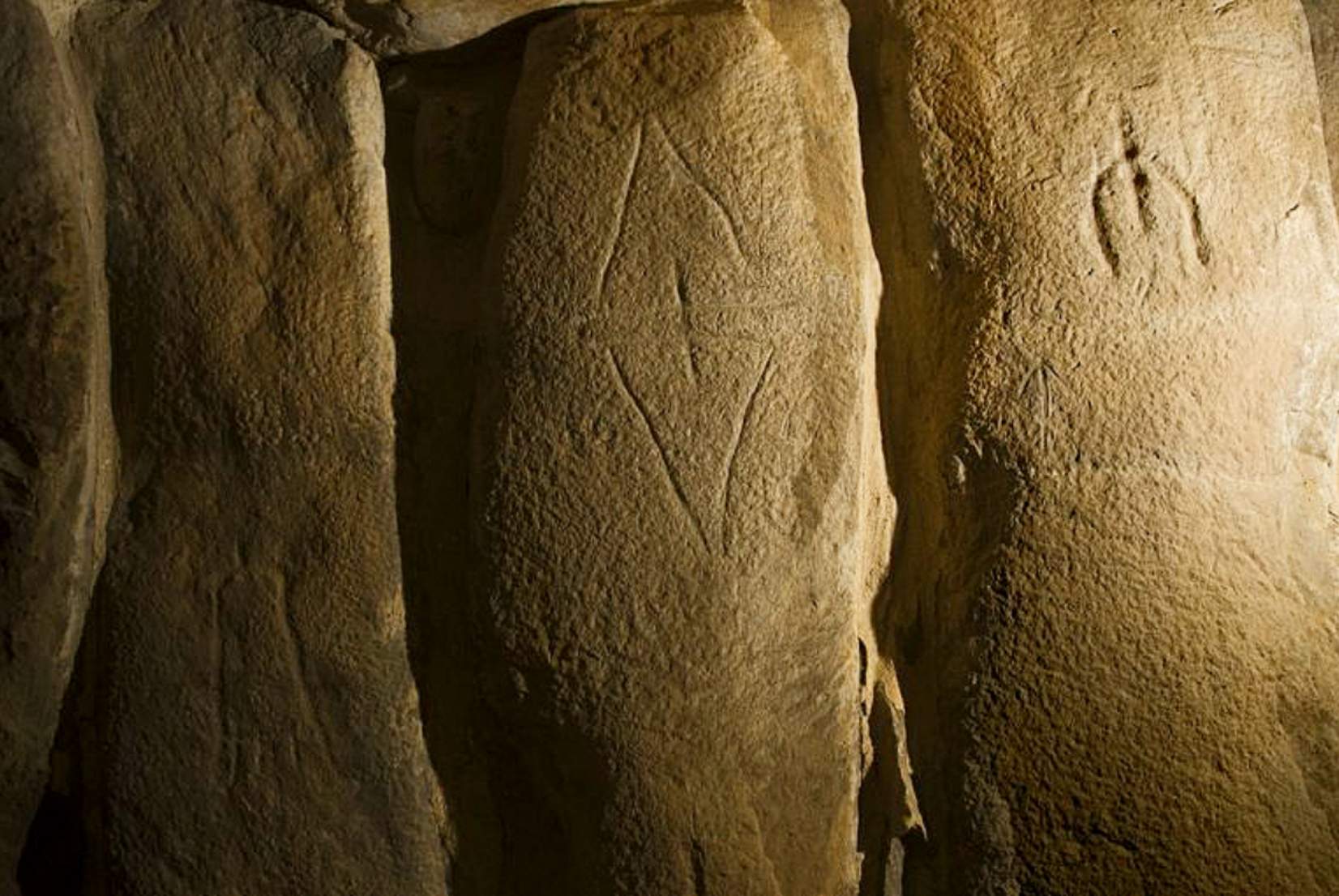

As a result of modern technologies used by experts, they have discovered ancient drawings on the stones, and many of them depict people armed with daggers, staffs, and axes. Surprisingly, no other megalithic structure in Europe has as many well-armed figures as Dolmen de Soto, according to the analysis. The question that arises from this is, were the people who lived in the past afraid of anyone or anything?

Recent archaeological finds uncovered and proved the existence of a Neolithic stone circle that measures 65 meters in diameter and has been dated to between 5,000 and 4,000 BC. The construction of the circle was done with stones of varied sizes and shapes.

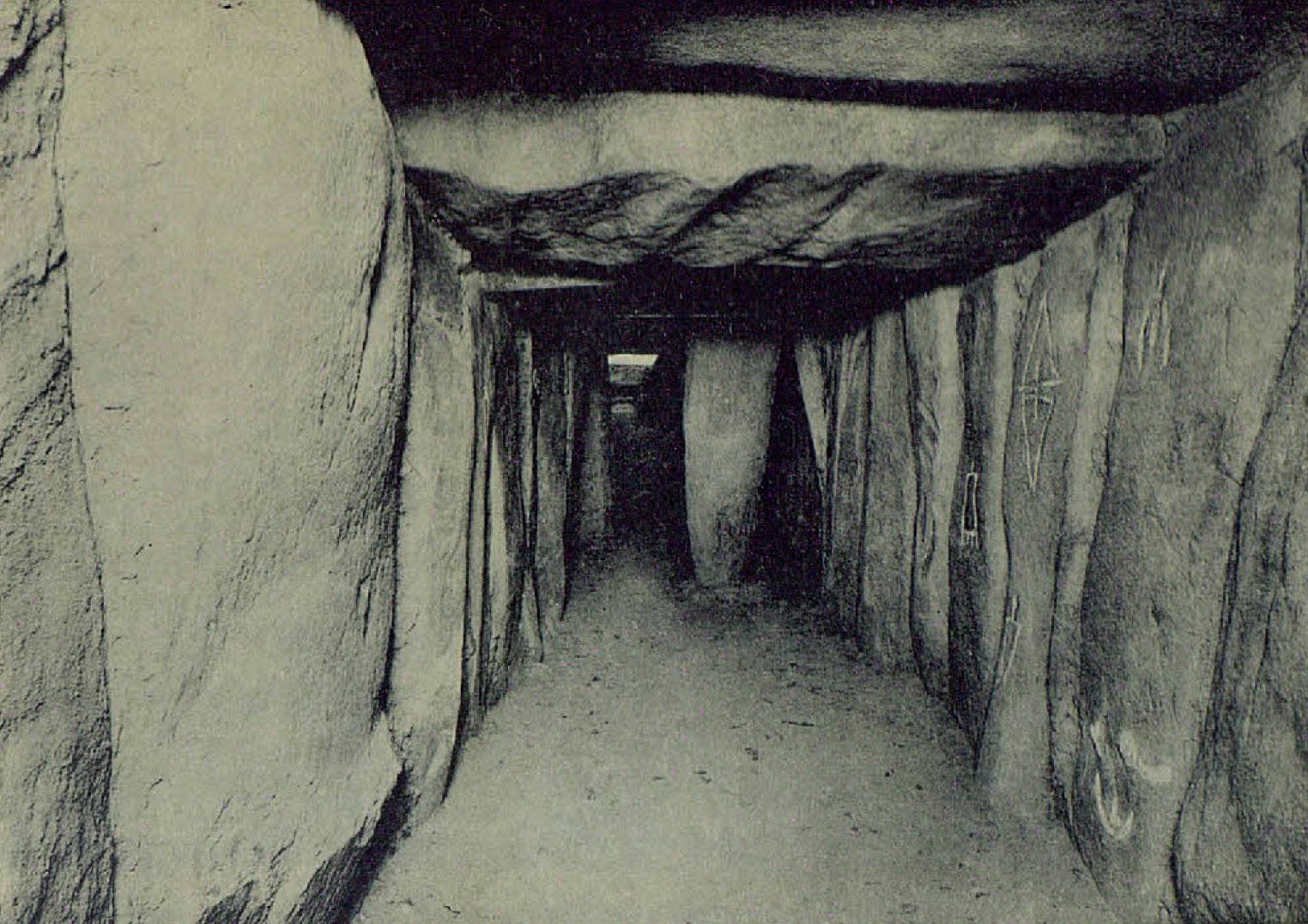

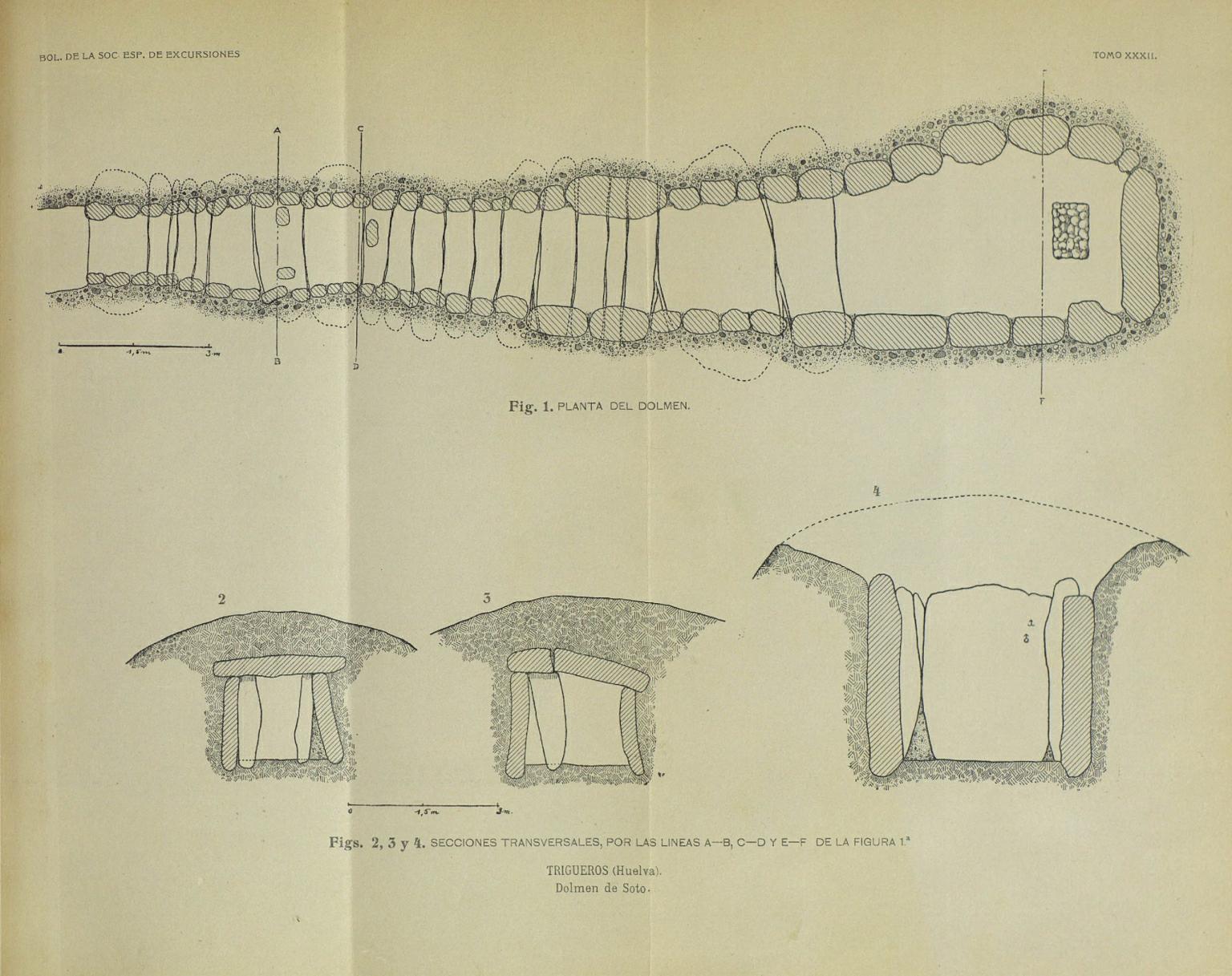

The 21 meter underground passage begins narrow and widens to three meters in width and height as it approaches the monument’s back. On the inside is a gallery that has 63 stone pillars, a frontal slab, and 30 more stones covering it for coverage.

Was this megalith a place of worship for the cult of death? Or perhaps was it a site where devotion was paid to various gods and other forms of divinity? Dolmen de Soto served what purpose?

Was there a cemetery there? If this is the case, how come there are only a few bodies buried in such a large underground complex? How exactly was it put together? There are a lot of questions, but not all of them have clear explanations.

There are 94 granite pillars surrounding the walls of the dolmen, which was built between 3000 and 2500 BC and has an anthropomorphic stele with a human face, belt, and trident, very similar to the dolmen on the Channel Island of Guernsey.

The Dolmen de Soto was discovered in 1923 by Armando de Soto Morillas, and subsequently excavated over three consecutive seasons by the German archaeologist Hugo Obermaier, who shed light on its architecture, an enormous quantity of engravings, and various stelae used more than once.

Dolmen de Soto is astronomically oriented towards the east and perfectly matches the sunrise at the spring and autumn equinoxes. At the time of the equinox, the first rays of the sun shine through the corridor and are cast upon a specific chamber that is situated at the easternmost point of the Dolmen’s passage. It gives the impression that the ancient people had a symbolic ritual in which the deceased was reborn experiencing sunlight.

The underground structure of the long corridor dolmens family is the most extensive megalithic facility in the Huelva province. It is almost 21m long, though its width varies from 0,82m at the door up to 3.1m.

Experts discovered a metalworking workshop inside the mound dating around 3,000 BC, indicating that the engravings of the weapons are most likely related to the discovery of metallurgy.

Only eight bodies have been found inside the Dolmen, buried in seven different places. The bodies appear crouched near the wall and have orthostats, decorated with a few engravings showing the image of the deceased, his protecting totemic sign, or some of his weapons.

As can be seen, we know a lot about Dolmen de Soto today, yet there’s still a lot we don’t know. Doubtful, the mystery of this significant Neolithic landmark will be ever definitely solved even with modern techniques.

The problem is that the eight bodies buried in seven different places inside the Dolmen are missing! The bodies and their belongings were taken from Dolmen de Soto and transported to the United Kingdom. Their whereabouts are unknown.

“If we had access to the ancient bodies found at the site, we could learn more about this fascinating place. It’s a pity these human remains and artifacts were never analyzed” said Mimi Bueno-Ramrez, professor of prehistory at Alcalá de Henares University in Madrid. Dolmen De Soto’s history is incomplete without this missing piece.