A theory put forward by Professor Ivan Watkins states that the ancient people of the world were able to cut stone by harnessing the power of the Sun. Obviously, many do not believe that simple tools were enough to create some of the truly wondrous ancient stone monuments seen on just every continent of the world. From Machu Picchu in South America to the Giza Plateau in Egypt, every ancient monument has led us to think and strongly believe that ancient aliens are responsible for these ancient mega projects.

Of course, one could interpret ancient writings images and structures in a number of different ways but some intellectuals believe there was once a far more advanced civilization that collapsed at the end of the last ice age ― the remnants of which became scattered around the world.

One thing is for sure, certain ancient monuments do show advanced methods of stonework. Some theorists believe it wasn’t due to the use of electricity and power tools, but a more efficient technology that harnessed natural forces such as the Sun, wind, water or sound.

The technology has not been recorded in history. But if natural forces were harnessed, there wouldn’t be much evidence recorded in the archaeological record apart from the product of that technology ― which is what we see in the form of perfectly drilled granites, intricate diorite vases, and perfectly fit in irregular stone walls. You can’t just drill or shape stone in the way you can wood or metal.

Especially, hard stones like granite or diorite as

they are made from extremely hard interlocking minerals that wear down tools before any real progress can even be made.

The ancient stone and metal tools (that we are told were used) would have very little impact on hard igneous rocks. So, archeology is certainly missing something in the modern age. It takes diamond tip tools and lots of cooling fluid to achieve the feats of stone masonry that we see in the distant past. And even now, it is a relatively slow and difficult process which brings us to another theory for how they achieved it by harnessing the power of sound tuning fork’s vibrations.

Sonic drilling and acoustic levitation are always that kind of sounds which can be utilized for technological gain, and are all scientifically feasible using not only modern but also ancient methods and materials. So, how does sonic drilling work?

Well, in simple terms, when sound vibrations of a specific frequency are sent through a drill bit or even through something as simple as a metal pipe, it can vibrate in such a way to act like a very high frequency jackhammer.

The drill barely needs to turn as the vibrational impacts and shattering do the job compared to conventional drilling. The method is actually faster thus less wear on the tool bits takes less energy. Conceivably, you can even turn the handle of a large tuning fork into a cutting rod whether it’s drill tube or a drill bits. Even a copper tube could conceivably cut into granites using this method.

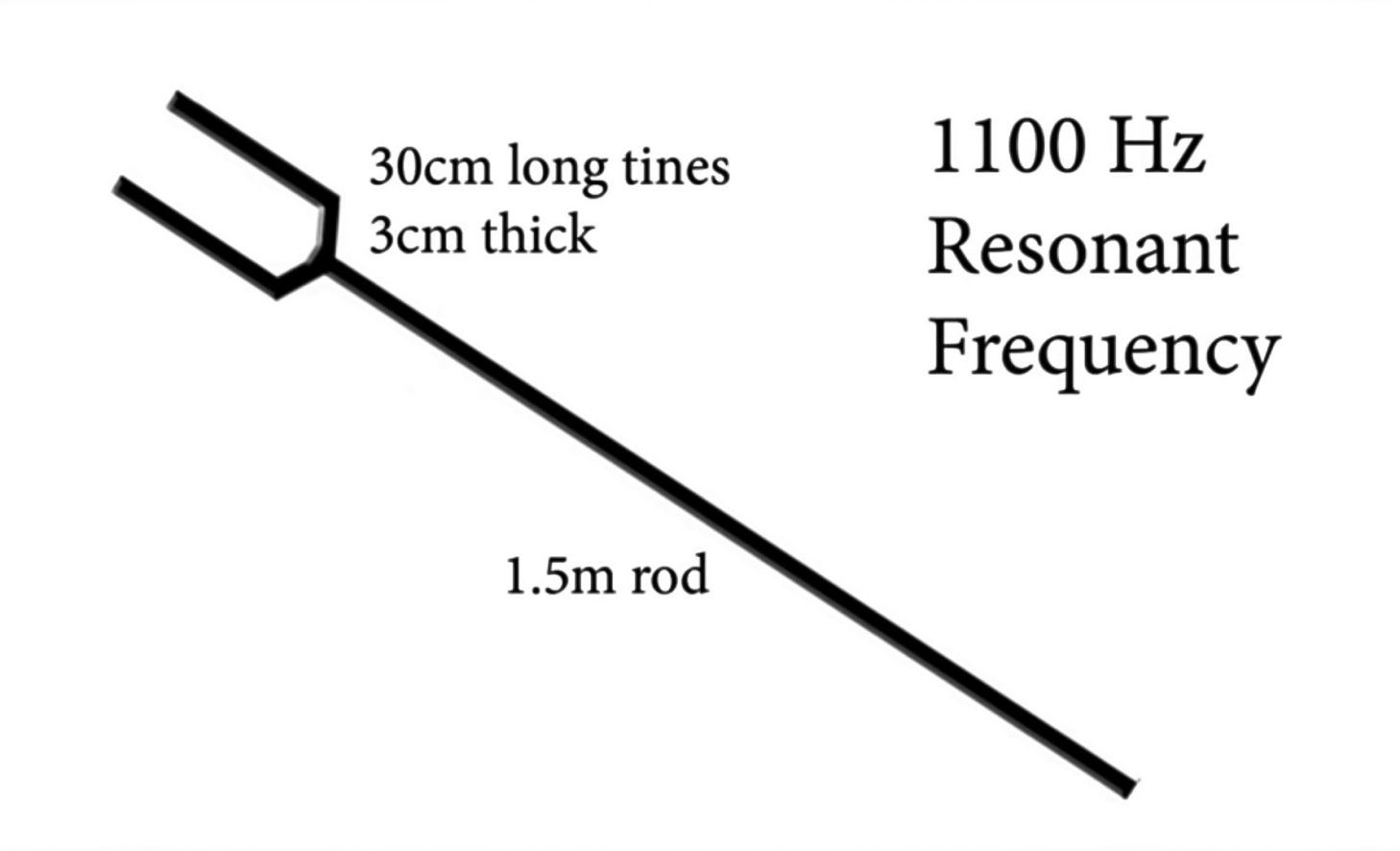

To turn a tuning fork into a sonic drill, the resonant frequency of the cutting rod must match the frequency of the fork that is attached to it.

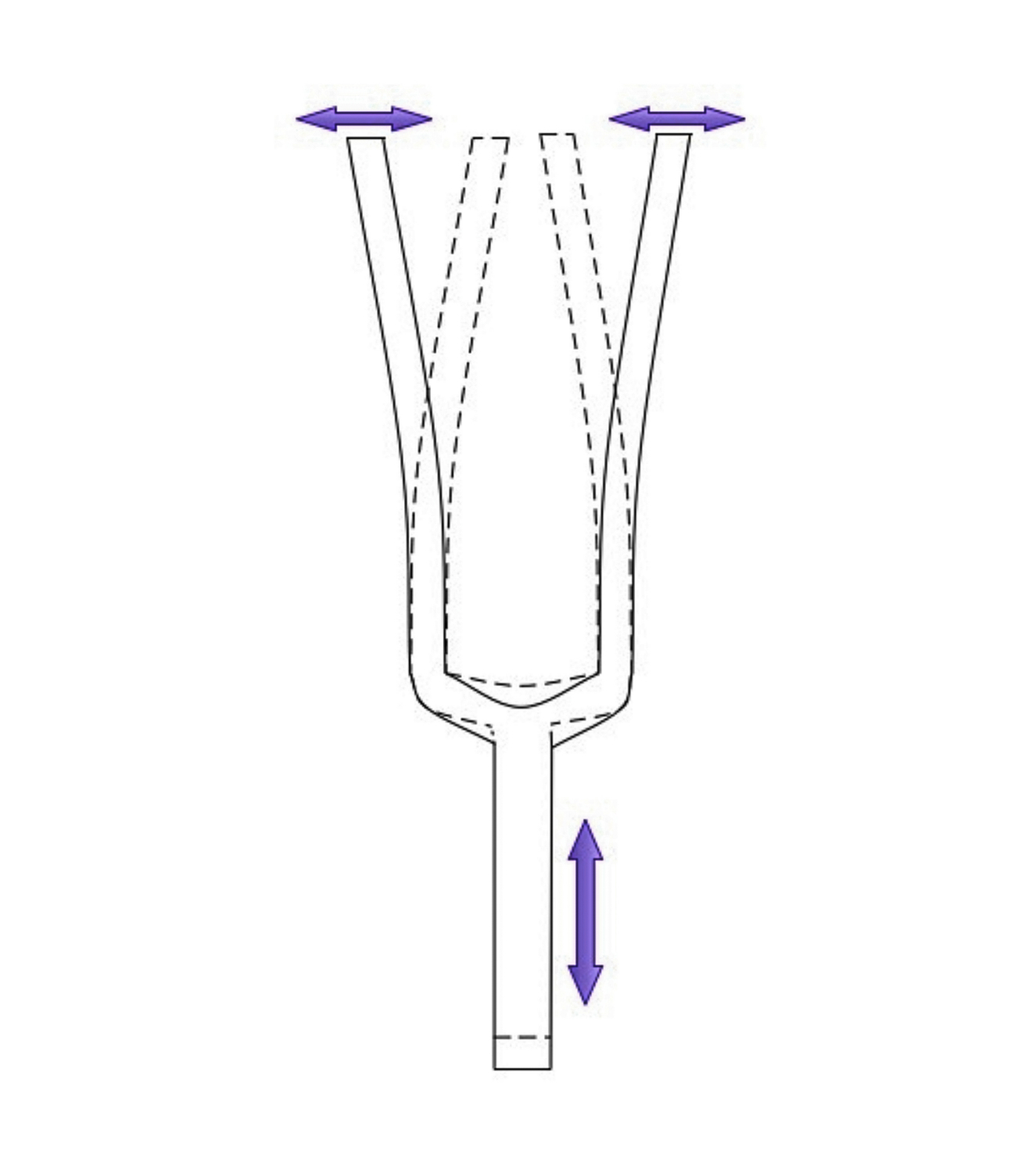

Scientifically, the way it works is the traverse vibrations from the fork prongs known as ‘tines’ move the bottom of the U-shape up and down. Which sends long eternal vibrations through the cutting rod up the rod’s resonant frequency. These vibrations create standing waves with maximum vibration at the beginning and the end of the rod and there is a point of no vibration in the middle where a handle could be attached.

For example, tines, 30 centimeters long and 3 centimeters thick, make a resonant frequency of 1,100 Hertz. An 1.5 meter long rod would be required to allow cutting.

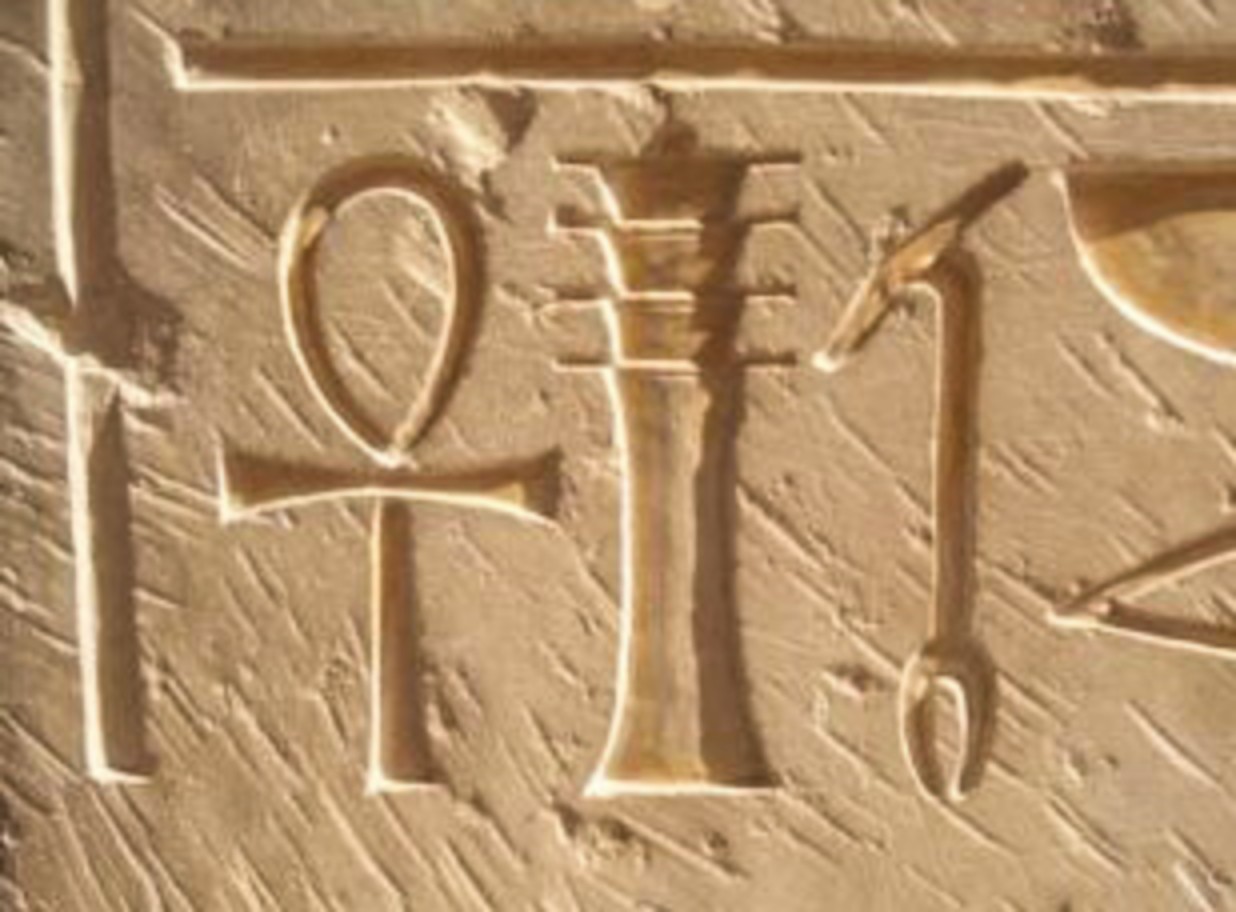

In Egyptian mythology the falcon god horus is associated with harpoons, but maybe the clearest evidence for sonic drilling has been staring us in the face for millennia.

One common symbol or object that is seen so often in ancient Egyptian art is the ‘scepter’. It appears in relics art and hieroglyphs associated with the ancient Egyptian religion. It is a long straight staff with a forked end. The opposite end is sometimes seen to be a stylized in animal head, but maybe this is actually a cutting implement.

The scepter was a symbol of power and Dominion. And although it has a number of other mythological and symbolic associations, may be, the true meaning got lost through the dynastic history of ancient Egypt. What became a symbol of power maybe once was literally an object of power. But mainstream historians and archaeologists attest, the traditional stone and metal tools were used to create stone blocks and ornaments. And this is all because of depictions of the art of stone working in war reliefs from the 5th dynasty all the way up to the 26th dynasty.

But for a start, when you analyze drilled Granites, it is clear that these methods certainly did not create the bore holes when you look at the holes that do not go all the way through the Granite. The circumference of the circular hole has a deeper groove, implying it was created with a metal pipe and it wouldn’t be possible to cut into granite simply using a metal pipe sound and manual labor as we are led to believe. But you can cut granite efficiently and quickly with a metal pipe if you use sonic drilling methods.

In ancient Egyptian images, we do see the use of simple hand tools to make stone vases and bowls. But such a method even in conjunction with sand wouldn’t be able to efficiently grind stone such as granite or diorite, and create the striations or tool marks that we see inside drilled Egyptian artifacts.

Furthermore, the most amazing and most difficult stonework created from the hardest stones are usually in Old Kingdom, predating the 5th dynasty, and many were actually pre-dynastic. There is no doubt that the stonework from the 5th dynasty onwards could have been created from the simple stone tools, as the rock used to make such artifacts was usually softer such as alabaster sandstone and limestone.

The oldest depiction of a rock drill is a hieroglyph known as U24, first seen in a 3rd dynasty tomb. May be the hieroglyph is actually depicting a tuning fork tool and not a depiction of a traditional hand crank rock drill as we are told.

Some researchers believe they have found ancient Egyptian carvings of two tuning forks attached by wires on a statue of Isis and Anubis. This is one way you could get them to resonate to a specific frequency for a prolonged amount of time to cut stone without hitting them with a hammer.

There is also another image from a Sumerian cylinder seal showing a musical scene and a musician is clearly seen holding a tuning fork.

Many independent researchers have proved that you can bore holes through solid rock with copper tubing, using sonic drilling methods. And with new research into ancient megalithic sites across the world, we are finding out that acoustics were widely understood by the ancients and was certainly taken into account when building stone structures.

This relatively new line of archeological research is known as ‘Archaeoacoustics’ and is observed at sites such as Stonehenge in England, Adam’s Calendar in South Africa, and Gobekli Tepe in Turkey ― not to mention the Great Pyramid of Egypt. They all share unquestionable acoustic properties that could well have amplified sound waves to vibrate fork tools at a constant pitch and allow the seemingly advanced method of stone cutting that has eluded historical researchers for so many years.