An ancient Elpistostege fish fossil found in Miguasha, Canada has revealed new insights into how the human hand evolved from fish fins.

An international team of paleontologists from Flinders University in Australia and Universite du Quebec a Rimouski in Canada have revealed the fish specimen has yielded the missing evolutionary link in the fish to tetrapod transition, as fish began to foray in habitats such as shallow water and land during the Late Devonian period millions of years ago.

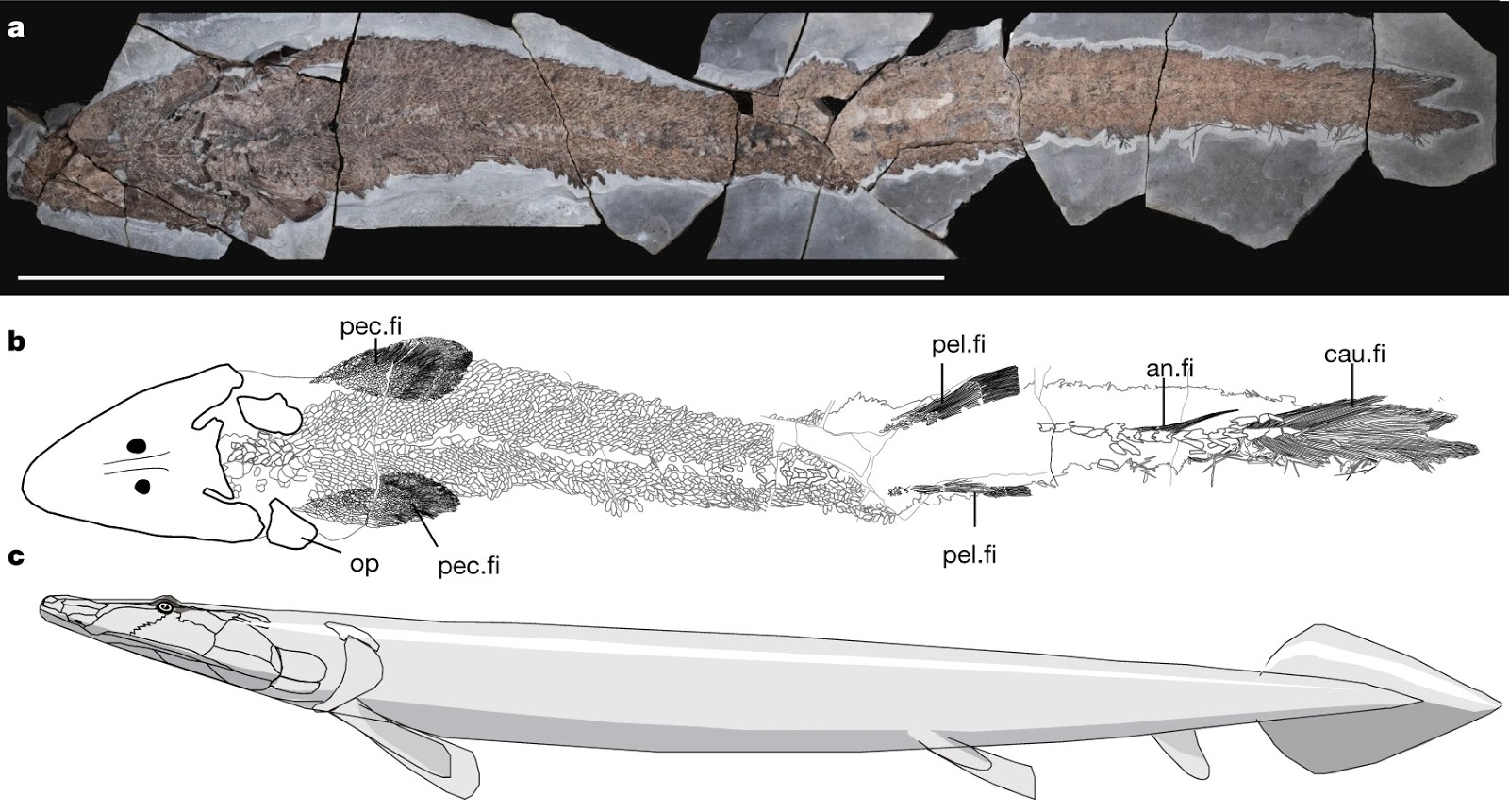

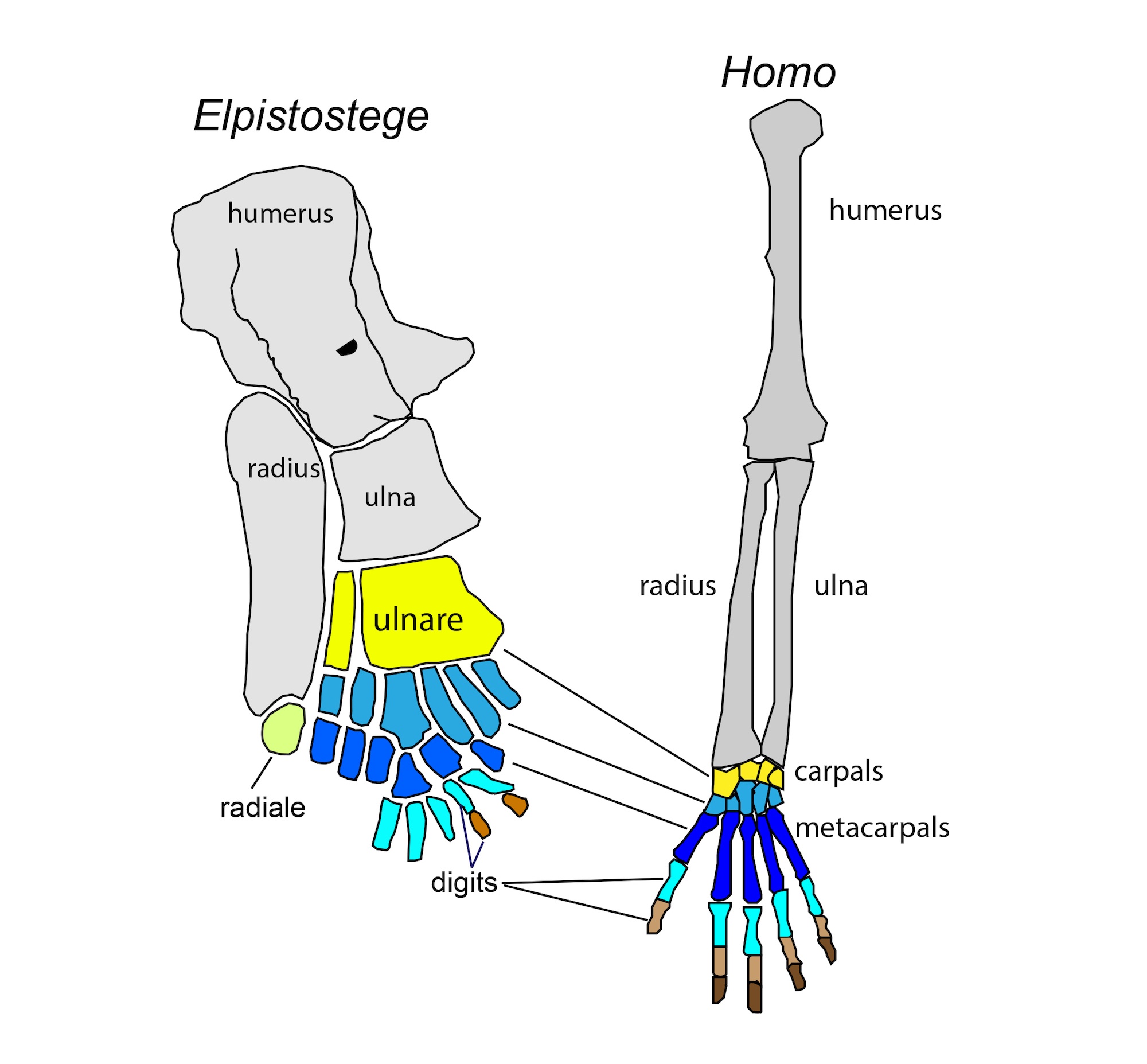

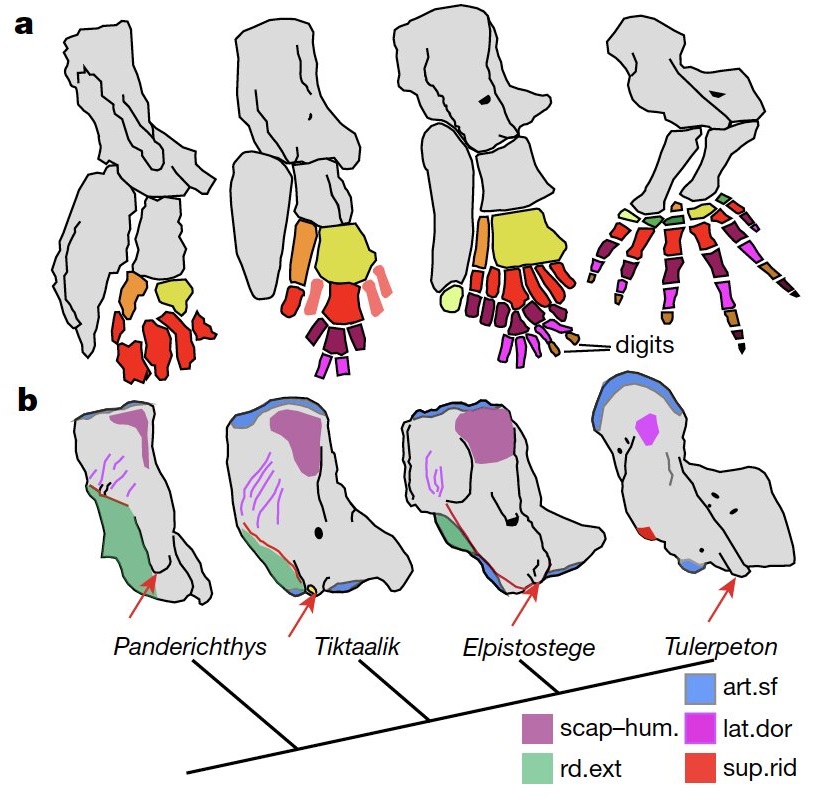

This complete 1.57 meter-long fish shows the complete arm (pectoral fin) skeleton for the first time in any elpistostegalian fish. Using high energy CT-scans, the skeleton of the pectoral fin revealed the presence of a humerus (arm), radius and ulna (forearm), rows of carpus (wrist) and phalanges organized in digits (fingers).

According to John Long, Strategic Professor in Palaeontology at Flinders University the discovery of a complete specimen of a tetrapod-like fish called Elpistostege, reveals extraordinary new information about the evolution of the vertebrate hand.

“This is the first time that we have unequivocally discovered fingers locked in a fin with fin-rays in any known fish. The articulating digits in the fin are like the finger bones found in the hands of most animals.”

“This finding pushes back the origin of digits in vertebrates to the fish level, and tells us that the patterning for the vertebrate hand was first developed deep in evolution, just before fishes left the water,” said Professor Long.

The evolution of fishes into tetrapods – four-legged vertebrates of which humans belong – was one of the most significant events in the history of life.

Vertebrates (back-boned animals) were then able to leave the water and conquer land. In order to complete this transition- one of the most significant changes was the evolution of hands and feet.

In order to understand the evolution from a fish fin to a tetrapod limb, paleontologists study the fossils of lobe-finned fish and tetrapods from the Middle and Upper Devonian (393-359 million years ago) known as ‘elpistostegalians’.

These include the well-known Tiktaalik from Arctic Canada, known only from incomplete specimens.

Co-author Richard Cloutier from Universite du Quebec a Rimouski says over the past decade, fossils informing the fish-to-tetrapod transition have helped to better understand anatomical transformations associated with breathing, hearing, and feeding, as the habitat changed from water to land on Earth.

“The origin of digits relates to developing the capability for the fish to support its weight in shallow water or for short trips out on land. The increased number of small bones in the fin allows more planes of flexibility to spread out its weight through the fin.”

“The other features the study revealed concerning the structure of the upper arm bone or humerus, which also shows features present that are shared with early amphibians. Elpistostege is not necessarily our ancestor, but it is closest we can get to a true ‘transitional fossil’, an intermediate between fishes and tetrapods.”

Elpistostege was the largest predator living in a shallow marine to estuarine habitat of Quebec about 380 million years ago. It had powerful sharp fangs in its mouth so could have fed upon several of the larger extinct lobe-finned fishes found fossilized in the same deposits.

Elpistostege was originally named from just a small part of the skull roof, found in the fossiliferous cliffs of Miguasha National Park, Quebec, and described in 1938 as belonging to an early tetrapod.

Another part of the skull of this enigmatic beast was found and described in 1985, demonstrating it was really an advanced lobe-finned fish. The remarkable new complete specimen of Elpistostege was discovered in 2010.

The study originally published in the journal Nature. 18 March 2020.