A 1,200 years old Egyptian text, tells part of the crucifixion story of Jesus with apocryphal plot twists, some of which have never been seen before. Written in the Coptic language, the ancient text tells of Pontius Pilate, the judge who authorized Jesus’ crucifixion, having dinner with Jesus before his crucifixion and offering to sacrifice his own son in the place of Jesus. It also explains why Judas used a kiss, specifically, to betray Jesus — because Jesus had the ability to change shape, according to the text — and it puts the day of the arrest of Jesus on Tuesday evening rather than Thursday evening, something that contravenes the Easter timeline.

The discovery of the text doesn’t mean these events happened, but rather that some people living at the time appear to have believed in them, said Roelof van den Broek of Utrecht University in the Netherlands, who published the translation in the book “Pseudo-Cyril of Jerusalem on the Life and the Passion of Christ” (Brill, 2013).

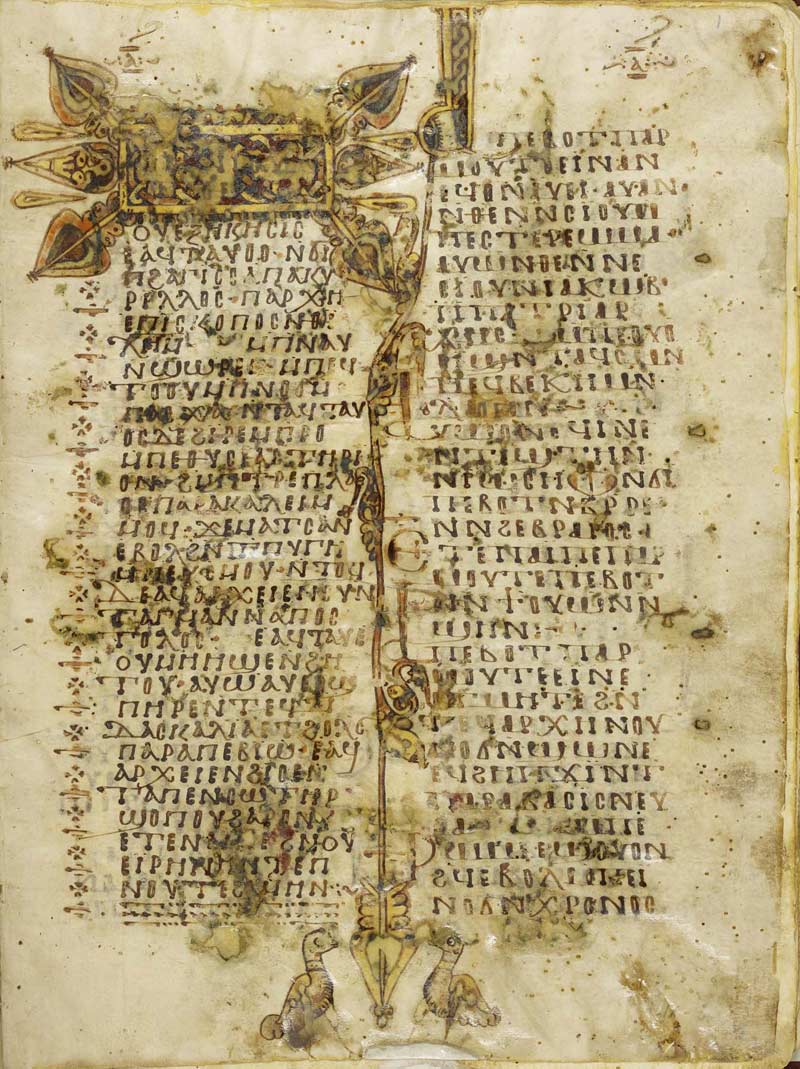

Copies of the text are found in two manuscripts, one in the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City and the other at the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania. Most of the translation comes from the New York text, because the relevant text in the Pennsylvania manuscript is mostly illegible.

Pontius Pilate has dinner with Jesus

While apocryphal stories about Pilate are known from ancient times, van den Broek wrote in an email to LiveScience that he has never seen this one before, with Pilate offering to sacrifice his own son in the place of Jesus.

“Without further ado, Pilate prepared a table and he ate with Jesus on the fifth day of the week. And Jesus blessed Pilate and his whole house,” reads part of the text in translation. Pilate later tells Jesus, “well then, behold, the night has come, rise and withdraw, and when the morning comes and they accuse me because of you, I shall give them the only son I have so that they can kill him in your place.”

In the text, Jesus comforts him, saying, “Oh Pilate, you have been deemed worthy of a great grace because you have shown a good disposition to me.” Jesus also showed Pilate that he can escape if he chose to. “Pilate, then, looked at Jesus and, behold, he became incorporeal: He did not see him for a long time …” the text read.

Pilate and his wife both have visions that night that show an eagle (representing Jesus) being killed. In the Coptic and Ethiopian churches, Pilate is regarded as a saint, which explains the sympathetic portrayal in the text, van den Broek writes.

The reason for Judas using a kiss

In the canonical Bible, the apostle Judas betrays Jesus in exchange for money by using a kiss to identify him leading to Jesus’ arrest. This apocryphal tale explains that the reason Judas used a kiss, specifically, is because Jesus had the ability to change shape.

“Then the Jews said to Judas: How shall we arrest him (Jesus), for he does not have a single shape but his appearance changes. Sometimes he is ruddy, sometimes he is white, sometimes he is red, sometimes he is wheat coloured, sometimes he is pallid like ascetics, sometimes he is a youth, sometimes an old man …” This leads Judas to suggest using a kiss as a means to identify him. If Judas had given the arresters a description of Jesus he could have changed shape. By kissing Jesus, Judas tells the people exactly who he is.

This understanding of Judas’ kiss goes way back. “This explanation of Judas’ kiss is first found in Origen (a theologian who lived A.D. 185-254),” van den Broek writes. In his work “Contra Celsum,” the ancient writer Origen stated that “to those who saw him (Jesus) he did not appear alike to all.”

St. Cyril impersonation

The text is written in the name of St. Cyril of Jerusalem who lived during the fourth century. In the story, Cyril tells the Easter story as part of a homily (a type of sermon). A number of texts in ancient times claim to be homilies by St. Cyril, and they were probably not given by the saint in real life, van den Broek explained in his book.

Near the beginning of the text, Cyril, or the person writing in his name, claims that a book has been found in Jerusalem showing the writings of the apostles on the life and crucifixion of Jesus. “Listen to me, oh my honoured children, and let me tell you something of what we found written in the house of Mary …” reads part of the text.

Again, it’s unlikely that such a book was found in real life. Van den Broek said that a claim like this would have been used by the writer “to enhance the credibility of the peculiar views and uncanonical facts he is about to present by ascribing them to an apostolic source,” adding that examples of this plot device can be found “frequently” in Coptic literature.

Arrest on Tuesday

Van den Broek says that he is surprised that the writer of the text moved the date of Jesus’ Last Supper, with the apostles, and arrest to Tuesday. In fact, in this text, Jesus’ actual Last Supper appears to be with Pontius Pilate. In between his arrest and supper with Pilate, he is brought before Caiaphas and Herod.

In the canonical texts, the last supper and arrest of Jesus happens on Thursday evening, and present-day Christians mark this event with Maundy Thursday services. It “remains remarkable that Pseudo-Cyril relates the story of Jesus’ arrest on Tuesday evening as if the canonical story about his arrest on Thursday evening (which was commemorated each year in the services of Holy Week) did not exist!” van den Broek wrote in the email.

Who believed it?

Van den Broek writes in the email that “in Egypt, the Bible had already become canonized in the fourth/fifth century, but apocryphal stories and books remained popular among the Egyptian Christians, especially among monks.”

Whereas the people of the monastery would have believed the newly translated text, “in particular the more simple monks,” he’s not convinced that the writer of the text believed everything he was writing down, van den Broek said.

“I find it difficult to believe that he really did, but some details, for instance the meal with Jesus, he may have believed to have really happened,” van den Broek writes. “The people of that time, even if they were well-educated, did not have a critical historical attitude. Miracles were quite possible, and why should an old story not be true?”