The earth is a treasure trove of secrets and hidden gems, and one of the most fascinating is the discovery of ancient animals that have been perfectly preserved in permafrost.

In 2018, a lucky mammoth tusk hunter exploring the shores of the Tirekhtyak River in Siberia’s Yakutia region discovered something amazing – the fully intact head of a prehistoric wolf.

The discovery is considered to be a significant find as it provides an unprecedented insight into the lives of animals that lived thousands of years ago.

The specimen, which has been preserved for 32,000 years by the region’s permafrost, is the only partial carcass of an adult Pleistocene steppe wolf – an extinct lineage separate from modern wolves – ever discovered.

The discovery, first published by the Siberian Times, is expected to assist experts in better understanding how steppe wolves differed from modern equivalents, as well as why the species became extinct.

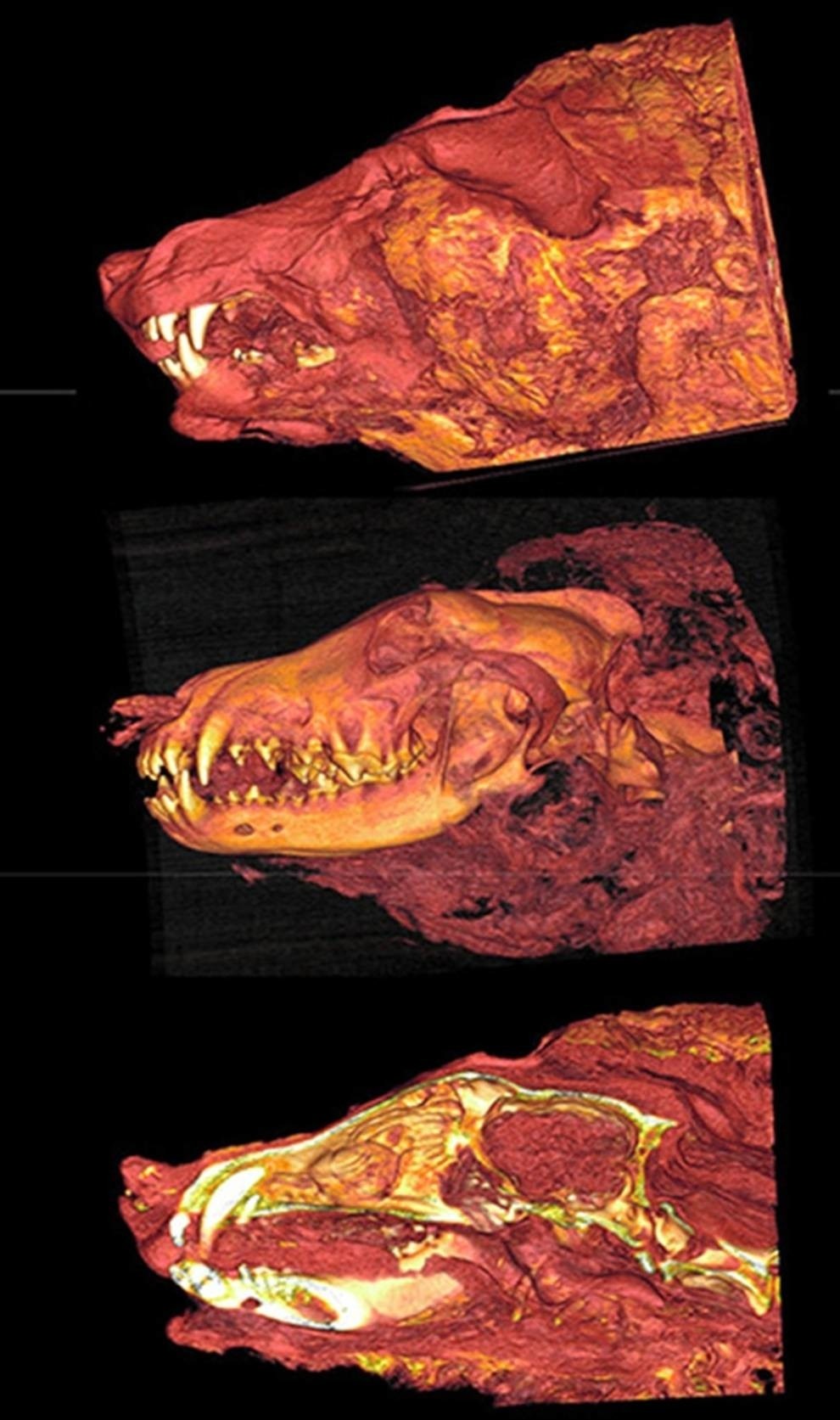

According to Marisa Iati of the Washington Post, the wolf in issue was fully developed at the time of its death, perhaps around 2 to 4 years old. Although photographs of the severed head, still boasting clumps of fur, fangs, and a well-preserved snout, place its size at 15.7 inches long – the modern gray wolf’s head, in comparison, measures 9.1 to 11 inches.

Love Dalén, an evolutionary geneticist at the Swedish Museum of Natural History who was filming a documentary in Siberia when the tusk hunter arrived on the scene with the head in tow, says that media reports touting the find as a “giant wolf” are inaccurate.

According to Dalén, it is not that much bigger than a modern wolf if you discount the frozen clump of permafrost stuck to where the neck would normally have been.

According to CNN, a Russian team led by Albert Protopopov of the Republic of Sakha’s Academy of Sciences is preparing to build a digital model of the animal’s brain and the interior of its skull.

Given the state of preservation of the head, he and his colleagues are hopeful that they may extract viable DNA and use it to sequence the wolf’s genome according to David Stanton, a researcher at the Swedish Museum of Natural History who is directing the genetic examination of the bones. For the time being, it is unknown how the wolf’s head became detached from the rest of its body.

Tori Herridge, an evolutionary biologist at London’s Natural History Museum who was part of the team filming in Siberia at the time of the discovery, says that a colleague, Dan Fisher of the University of Michigan, thinks scans of the animal’s head may reveal evidence of it being deliberately severed by humans – perhaps “contemporaneously with the wolf dying.”

If so, Herridge notes, the find would offer “a unique example of human interaction with carnivores.” Still, she concludes in a post on Twitter, “I am reserving judgment until more investigation is done.”

Dalén echoes Herridge’s hesitancy, saying that he has “seen no evidence convincing” him that humans cut off the head. After all, it’s not uncommon to find partial sets of remains in the Siberian permafrost.

For example, if an animal was only partially buried and then frozen, the rest of its body could have rotted or been eaten by scavengers. Alternatively, fluctuations in the permafrost over thousands of years could have caused the body to shatter into several pieces.

According to Stanton, steppe wolves were “probably slightly larger and more robust than modern wolves.” The animals had a strong, wide jaw equipped for hunting large herbivores such as woolly mammoths and rhinos, and as Stanton tells USA Today’s N’dea Yancey-Bragg, went extinct between 20,000 to 30,000 years ago, or roughly the time when modern wolves first arrived on the scene.

If the researchers are successful in extracting DNA from the wolf’s head, they will try to use it to determine whether ancient wolves mated with current ones, how inbred the earlier species was, and whether the lineage had – or lacked – any genetic adaptations that contributed to its extinction.

To date, the Siberian permafrost has yielded an array of well-preserved prehistoric creatures: among others, a 42,000-year-old foal, a cave lion cub, an “exquisite ice bird complete with feathers,” as Herridge notes, and “even a delicate Ice Age moth.”

According to Dalén, these finds can largely be attributed to a surge in mammoth tusk hunting and increased melting of permafrost linked with global warming.

Stanton concludes, “The warming climate … means that more and more of these specimens are likely to be found in the future.” At the same time, he points out, “It is also likely that many of them will thaw out and decompose (and therefore be lost) before anyone can find … and study them.”

The fact that this discovery was made by a mammoth tusk hunter only adds to the intrigue. It’s an exciting time for paleontologists and archeologists alike, as more and more discoveries are made that push the boundaries of our understanding of the past. We look forward to seeing what other amazing discoveries are made in the future!