Since the Cambrian Period, about 520 million years ago, arthropods have been highly successful creatures, representing roughly 80% of the total animal species on Earth. This is more than any other animal group, and they are also the most conspicuous and pervasive.

The evolution of arthropods and the form of their antecedent have been a major conundrum in the field of zoology, leaving researchers perplexed for more than a century.

The Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (NIGPAS) recently uncovered a shrimp-like fossil with five eyes, which has contributed to our knowledge of the early evolutionary history of arthropods. The findings were published in Nature on November 4, 2020.

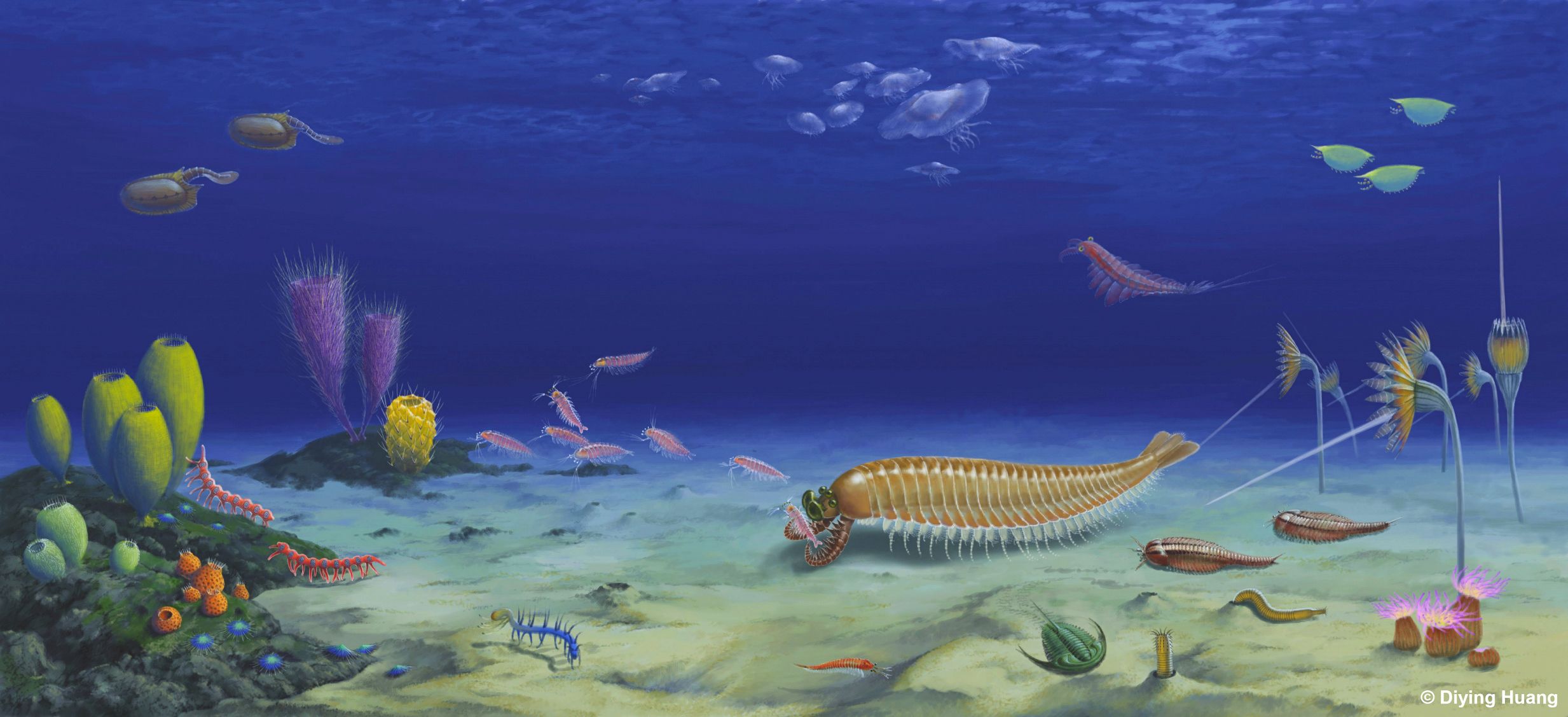

A species of fossil, Kylinxia, was recovered from the Chengjiang fauna located in Yunnan Province of southwest China. This fauna offers the most comprehensive early animal fossils from the Cambrian Period.

Diying Huang, a professor from NIGPAS and the corresponding author for the study, described Kylinxia as a very rare chimeric species. The organism displays morphological characteristics from multiple creatures, similar to the ‘Kylin’ – a mythical chimeric being – in Chinese mythology.

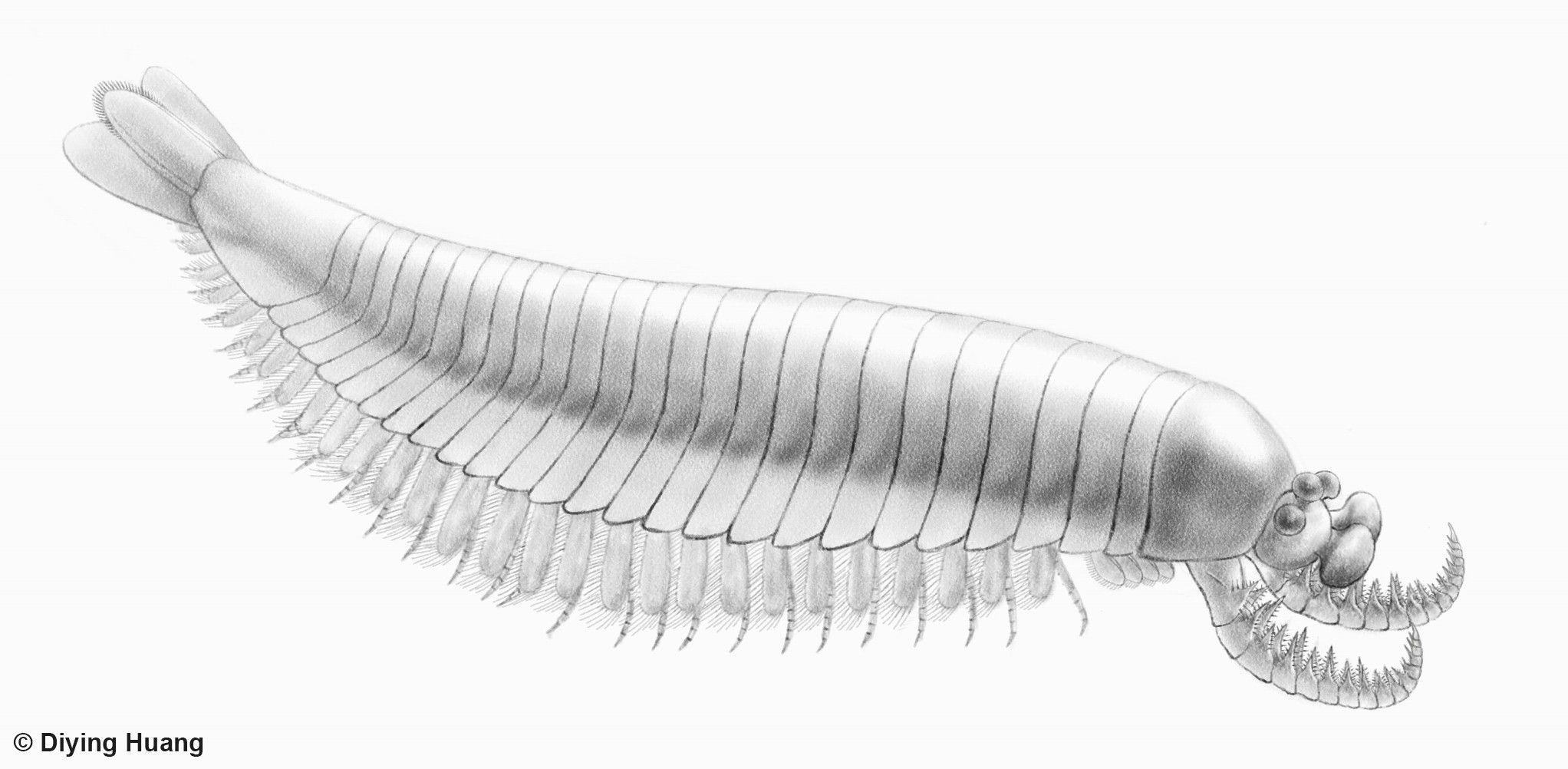

Prof. Zhao Fangchen, a co-corresponding author of the study, commented that the Kylinxia fossils show remarkable anatomy due to the unique taphonomic conditions. These fossils, he said, give us a chance to observe soft body parts, such as nervous tissue, eyes, and digestive system, which are usually absent in regular fossils.

Kylinxia is an organism that exhibits qualities of both advanced and primitive arthropods. It has a thick cuticle, segmented body, and jointed legs like a modern arthropod, but it also has five eyes like Opabinia, the Cambrian “weird wonder,” and the famous raptorial appendages of Anomalocaris, the dominant predator of the Cambrian sea.

The Chengjiang fauna contains Anomalocaris, a top predator that can be up to two meters long and is often seen as an ancestor of arthropods. However, the differences between Anomalocaris and genuine arthropods are extensive, making it difficult to bridge the evolutionary gap between them. This void has become a critical “missing link” in understanding the beginnings of arthropods.

The research team studied the anatomy of the fossils of Kylinxia in detail. They showed that the initial limbs in Anomalocaris and true arthropods were homologous. The phylogenetic analysis suggested a relationship between Kylinxia’s front appendages, the tiny predatory appendages located in front of the mouth of Chelicerata (a group that includes spiders and scorpions), and the antennae of Mandibulata (a subdivision of arthropods including insects such as ants and bees).

Prof. Zhu Maoyan, a co-author of the research project, declared that the evolutionary position of Kylinxia is situated between Anomalocaris and the real arthropods, thus leading to the discovery of the evolutionary origin of the true arthropods.

Dr. Zeng Han, lead researcher of the study, commented that Kylinxia is an essential transitional fossil foreseen by Darwin’s evolutionary theory which links Anomalocaris to genuine arthropods, forming a major ‘missing link’ in the origin of arthropods and thereby providing robust fossil evidence for Darwin’s evolutionary theory of life.

The research was funded by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.