Archaeologists have unearthed an untouched discovery in Siberia. The skeletal remains of a charioteer have been identified with the presence of a metal object, leading to speculation for the first time that horse-drawn chariots may have been used in the region.

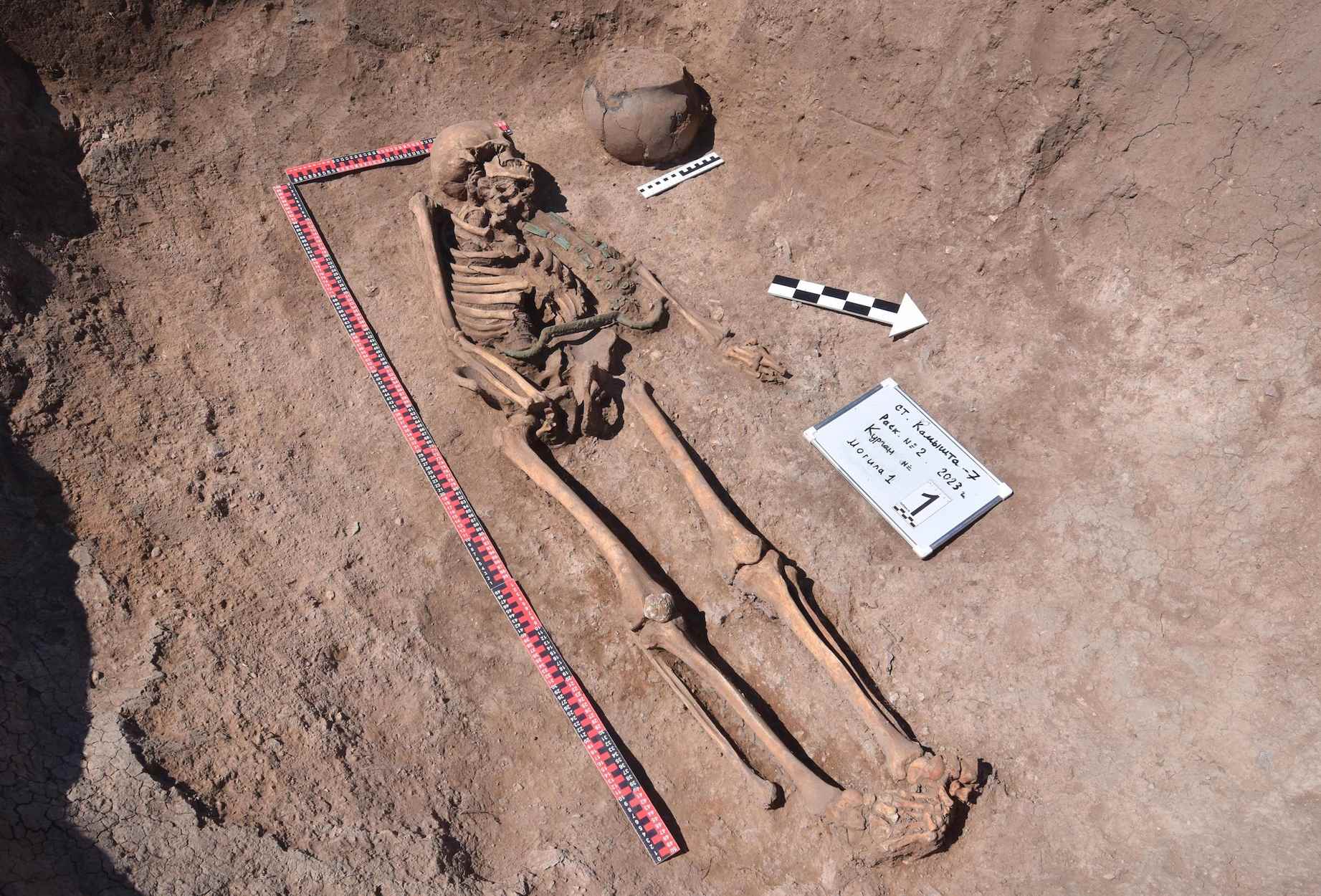

The remains, believed to be approximately 3,000 years old, were discovered accompanied by a bronze hooked metal object, which is believed to have been used for chariot driving. The hook enabled the driver to be fastened to the chariot from the waist, leaving the hands free. This metal piece was found around the waist of the skeleton, which has remained untouched since it was interred in the late Bronze Age.

The charioteer and other graves were discovered near the village of Kamyshta in Siberia. Archaeologists have spent years excavating this area before plans to expand the railway line are carried out. To date, no chariots have been found in the burial area. However, the item is similar to those found with Bronze Age charioteers in Mongolia and China.

The Lugav culture’s Bronze Age people were primarily cattle breeders, later replaced by the Scythian people of the Tagar culture during the Early Iron Age.

The grave also included an earthen mound over a square stone tomb, a bronze knife, and “bronze jewelry made of bronze plates with characteristic hemispherical plaque,” according to a press statement.

The researchers stated, in a translated statement, that they believe burials have been sanctioned in this region for four centuries, and the graves reveal three stages of the late Bronze Age, which was around the 11th century BC. These stages include the Karauk to Lugava culture transition, the middle stage with the Lugava culture, and the final stage with features of the Tagar culture’s Banino stage.

In the area, no chariot finds have been made yet. Nevertheless, horse-drawn carts were known in the region. The culture of the era constructed stone tombs with extended walls, resembling a carriage or sleigh. The team intends to carry on excavations to gain further insight into funeral customs during this time period.

This discovery opens new possibilities for understanding ancient civilizations’ mobility and trade networks.